Ljubljana related

With its 2864 metres of elevation, Triglav is the highest peak in Slovenia and the Julian Alps, and it’s said one only becomes a true Slovene after climbing it at least once. Triglav is also one of our national symbols and a central element on the coat of arms. Its name means “three-headed”, and could have come from its three-peak shape when seen from the south, or the Slavic god with the same name.

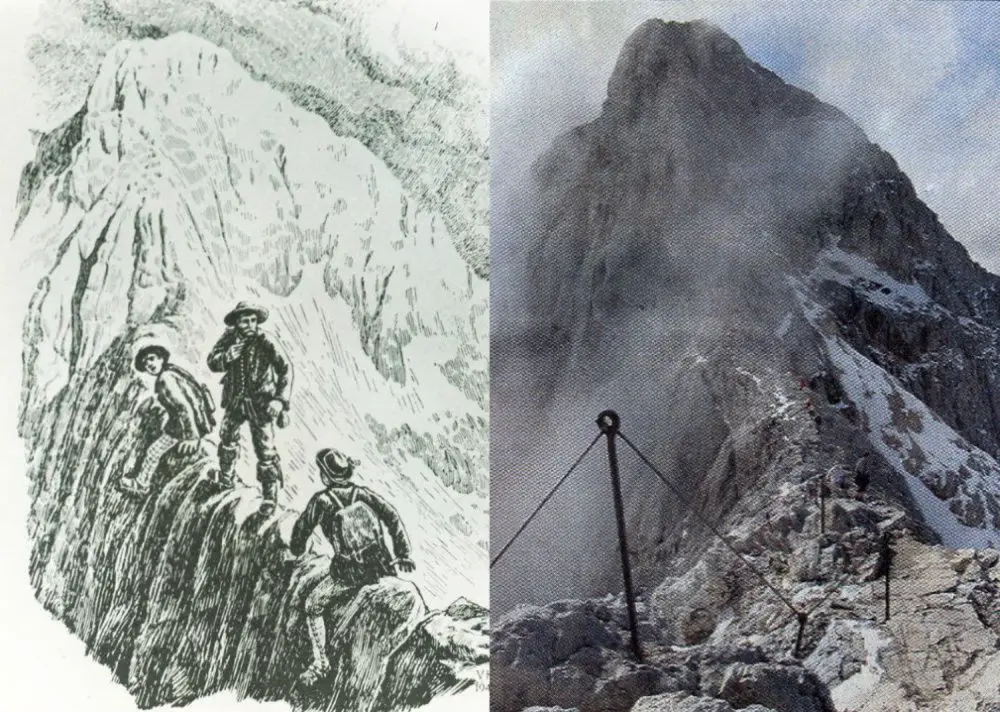

Triglav then and now

The first documented ascent to Triglav was accomplished in 1778. The “four brave men” from Bohinj made their way to its then still present glacier and traversed the sharp ridge to the peak. The ascent took three days, from the 24th to the 26th of August.

100 years later, when the people of Slovenia were struggling to establish their national identity inside the Austro-Hungarian empire, Slovene priest Jakob Aljaž bought a piece of land on the top of Triglav. There, he built a turret that characterizes the peak to this day. He was also the one to lay out plans for several hiking paths to its top. The dangerous and sharp ridge was flattened and made safer with a Via Ferrata, making it possible for more people to reach its peak.

Nowadays, Triglav is one of the most visited summits in Slovenia. Even though it still presents some risks and dangers, around 3000 hikers reach it daily at the height of the summer season. Apart from the symbolic value, the peak is also attractive because of its spectacular views from the centre of the Julian Alps. The prominent peak can be seen from most of Slovenia, always inviting those who see it to climb it.

How to climb Mt. Triglav

Even though many Slovenians do it, climbing Triglav is not that simple of an undertaking. Most of the trails leading to the peak take an approximate time of 6 hours of walking in one direction. That’s why most people choose to do it in two days, spending a night in one of the mountain huts close to its peak.

The most popular is the Triglav Hut on Kredarica, which at 2515 metres of elevation is the highest situated hut in Slovenia. The second choice for most hikers is the Planika Hut, located on the southern side of the mountain. Whichever one you choose, spending extra time in the moon-like landscape of the barren and rocky high-altitude karst of the Slovenian mountains is a must-have experience.

The best time to climb Triglav is August and September since all of the snow is gone. On sunny days of August, it can get pretty crowded, that’s why more and more people climb it in September or even June and July. Of course, early ascenders must research if there is still some snow on the route. Winters ascents are also possible but should only be tried by the most experienced mountaineers. Sometimes it is also possible to ski from the top, which is one of the hardest possible skiing in Slovenia one could try. Otherwise, a ski tour to the Kredarica hut is a must-do for every ski tourer in Slovenia.

All the paths lead to Triglav

There are many different trails from all sides that lead to the top. The least difficult one leads from the Krma Valley, one of the three Triglav glacial valleys. It is one most who want to climb Triglav in one day use since it’s also the shortest. Those who go on multiple-day hikes start from Pokljuka. The trail is a little longer but very scenic, taking advantage of your extra days in the mountains.

The steepest but also the most fun climbs start in the Vrata Valley. They are the most difficult since they have many Via Ferrata elements, which require some climbing skills. They lead you next to the Triglav North Face, the cradle of Slovenian alpinism. One of the bigger faces in the Alps is more than a kilometre high and around 4 km long. It has more than a hundred different climbing routes of different grades that attract a large number of alpinists each year.

A guide makes your experience safer and more enjoyable

Even though the trails leading to the top are of different overall difficulty, they all have a technical upper part. The last hour of every ascent is a Via Ferrata requiring proper equipment and enough experience in mountain climbing. Knowing something about the local weather is also necessary since you never want to be caught in a storm in that kind of terrain.

If you don’t have all of that experience and knowledge, choosing to climb with a guide is the most sensible option. They are certified professionals who spend their lives training how to make your hikes as safe and enjoyable as possible. They know the most optimal routes and how to make your ascents easier. Local guides are also fluent in English and can share some amazing insights about the mountains and the area. Besides all that, they can also help you book your beds in the huts that are very crowded in the high season.

To find the best way for you to climb Mount Triglav, check out this selection of guided Triglav tours.

STA, 21 August 2021 - Prime Minister Janez Janša and Interior Minister Aleš Hojs were heckled by anti-government protesters at a mountain hut below Mt Triglav, Slovenia's tallest peak, on Friday evening.

Video shared on social media and reports by media including N1 and Reporter show Janša and Hojs filmed being confronted by a group of protesters as they were sitting in front of the Kredarica mountain hut.

This was after anti-government protesters, who usually stage bicycle rallies in the centre of Ljubljana, marked the 70th week of protests by climbing Mt Triglav, bicycle in tow.

Various social media posts suggest the protesters and the government officials met by chance.

The interchange lasted several minutes, during which Janša and Hojs faced a barrage of criticism and insults while periodically exchanging statements with the protesters.

The authors of the video said Defence Minister Matej Tonin was also there, but he is not seen on video.

Tonin's party, New Slovenia (NSi), confirmed Tonin had climbed Mt Triglv on Friday independently, with a group of ministry officials.

On the way up he encountered protesters who hurled some insults at him and behaved inappropriately.

Reporter says a helicopter landed at the mountain hut at around 9:45 PM and took the officials to the valley.

The prime minister's office would not comment on the events beyond saying that Janša had gone to Triglav in his spare time.

Uroš Urbanija, the head of the Government Communications Office, tweeted that the actions by the protesters were "a primitive attack".

One of the activists, trade unionist Tea Jarc, subsequently wrote on Twitter that an opponent of the protest movement had punched her.

STA, 18 May 2021 - The sole national park in Slovenia is celebrating 60 years since the Valley of Triglav Lakes was declared the Triglav National Park (TNP), and 40 years since a key law was passed to protect virtually the entire Julian Alps mountain range in the country.

Spreading on an area of almost 84,000 hectares, the park in the northwestern-most part of the country in the Julian Alps covers around 4% of Slovenia's territory.

It is named after the country's highest mountain, Triglav, a 2,864-metre peak which lies practically at the heart of it.

Enthusiasts recognised the area's beauty and the diversity of its fauna and flora, as well as the need to protect it, more than 100 years ago.

In 1908, before any national park was declared in Europe, scientist Albin Belar came up with the idea to protect the area under Komarča around the Savica Waterfall.

Protection was eventually introduced in 1924 when an 1,400-hectare area of the Valley of Triglav Lakes was declared an Alpine park.

The park ceased to exist after WWII as the relevant contract expired in 1944, but was revived and expanded to 2,000 hectares in 1961, changing its name to today's.

On 27 May 1981, a new law was passed to protect almost the entire Julian Alps, with another law in 2010 expanding the national park to its present boundaries.

Apart from Triglav, the national park boasts a number of natural wonders, such as gorges, waterfalls and lakes, including Lake Bohinj, and several peaks higher than 2,000 metres.

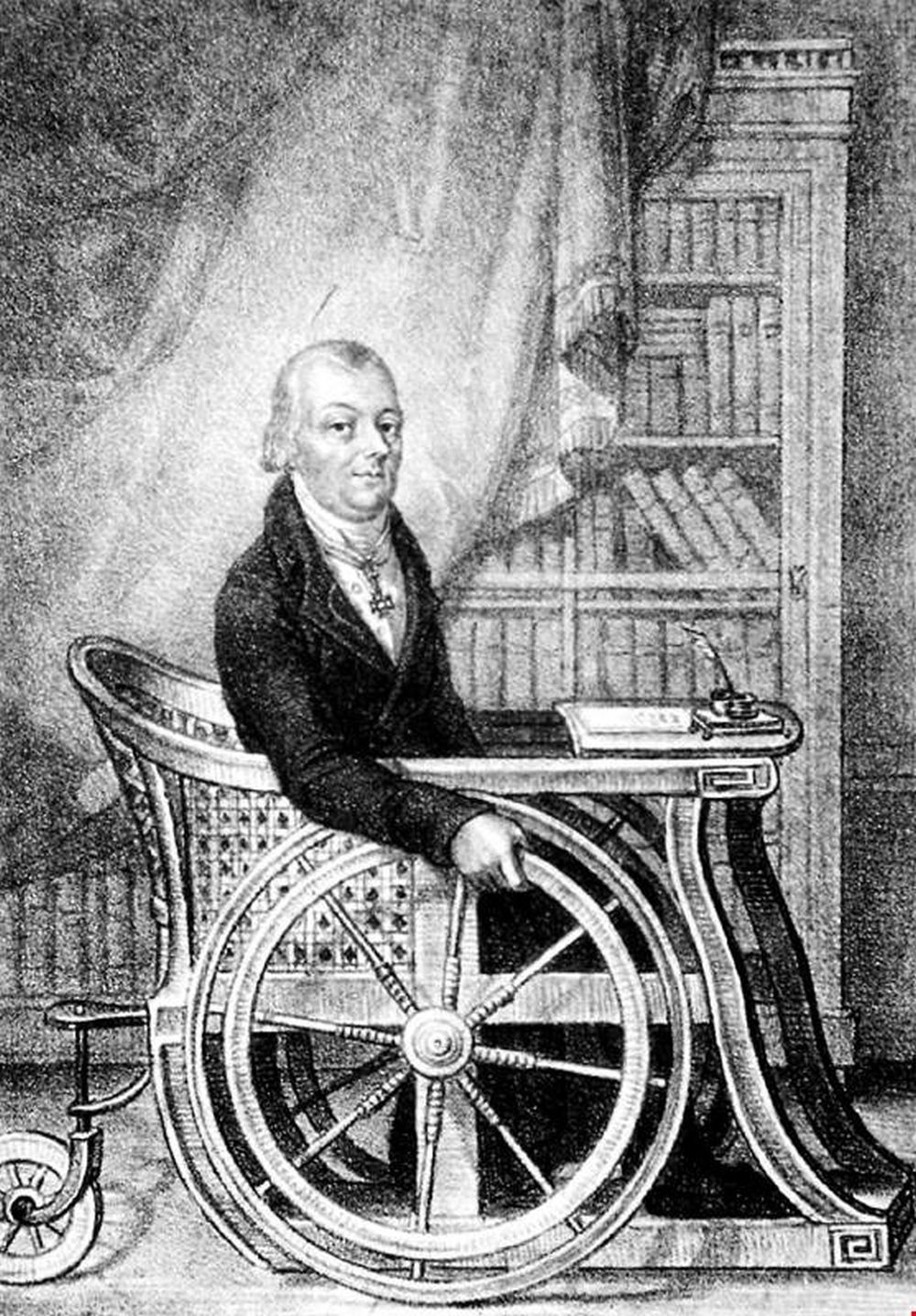

It is a popular tourist and hiking destination, with the first recorded ascent to Triglav in August 1778 credited to four locals upon initiative of Baron Žiga Zois.

But unlike national parks in Europe or the US, there are 34 settlements with some 2,700 residents in the TNP, who initially found the strict conservation regime limiting.

TNP director Janez Rakar says that all stakeholders have now realised protection is needed.

The locals' attitude towards the restrictions started changing when regulations on state co-funding of local projects started to be implemented.

"The state too has realised that the natural park is not just about occasionally bragging about it, but is really needed and shows the country's level of development."

He praised those who wrote the protective law to restrain the appetites for capital investments and restrict construction in the national park.

And although it is hard to precisely assess the effects of the protective law as social and climate change is happening, Rakar says "things would have been different without it".

"If there were no rules written down, the situation in this part of the natural environment would have been definitely different, and I dare say not better."

STA, 3 May 2021 - The Slovenian Olympic torch set out on its 81-day journey around Slovenia in Bovec on Monday to visit all 212 municipalities until 23 July, after it was taken to Triglav, the country's highest mountain, at the weekend. Over 5,000 runners will carry the symbol of the Olympic Games in the run-up to the Tokyo Summer Olympics.

The torch was brought to Bovec by athletes from Bovec area - footballer Primož Zorc, kayaker Igor Mlekuž and climber Tine Cuder, while ex-Alpine skier Miran Gašperšič had the honour of lighting it.

Mayor Valter Mlekuž said that it was a special honour for Bovec to see the Olympic torch begin its journey here.

Ex-runner Meta Mačus, head of the regional Olympic office in Nova Gorica, believes the torch will fill people with positive emotions and the Olympic spirit, as it connects the entire country.

The torch was then taken by up-and-coming athletes from Bovec area footballer Zala Kuštrin, freestyle skier Matej Bradaškja and runner Tobi Gabršček passing it on to three riders, who took it to the town of Kobarid.

Children from the Bovec primary school also took part in the launch ceremony, carrying banners with motivational slogans for Slovenian athletes, while year-eight gymnasts presented their skills.

The torch's journey is organised by the Slovenian Olympic Committee in collaboration with the police.

The torch is made of recycled steel and Slovenian beechwood, and will finish its journey in Ravne na Koroškem, where it was forged.

A foreign climber, with no details yet as to their name or nationality, fell to his death this morning while climbing Little Triglav, one of the peaks on the mountain’s ridge, with the body being recovered by a helicopter team. The Kranj Police Department noted that the man was well-equipped, and stressed that during the ongoing epidemic it’s better that people avoid all outdoor pursuits that could lead to significant injury, since rescue teams, health workers and other emergency services are already overwhelmed.

This echoed a recent call by the Slovenian Mountain Association (Planinska zveza Slovenije) that people should stick to easier walks and hikes near their homes during this period, stating: "To prevent the spread of the new coronavirus, we will do the most we can to stay home - the mountains will wait for us, and the mountain huts have closed their doors until further notice. Let's not stress ourselves unnecessarily in the mountains, so that this will not cause accidents and the additional burden on the rescue and medical staff. "

We see a lot of pictures from the top of Triglav, with people posing at the Aljaž Tower (Aljažev stolp) on the 2,864m peak. But we were curious what it looks like from above, and the general topography of the area, steepness of the slopes, and isolation. So here’s some videos of drones and light aircraft flying over the tallest mountain in Slovenia.

See how the Aljaž Tower has changed over time here while you can see the peak without the tower here. All our stories on Triglav are here

February 10, 2019

Read part one here and part two here.

The main task of the Slovenian Mountaineering Society (Slovensko Planinsko Društvo, SDP), established in 1893, was to build, take care and then walk along the secured mountain trails. One of the first important improvements on Triglav was securing some of the most problematic parts of the route leading to the summit. In the early 1870s, a local guide, Šest, and his son eased the trail from Triglav temple to Little Triglav, cut some very much needed steps into the rock, and secured the ridge between both peaks with iron poles with loops that carried a rope fence, which now allowed even more climbers to reach the summit.

In the years that followed, more trails were built and secured, allowing the ascent to the summit from several huts in various directions, including from the north. This is a route which used to cross the shrinking glacier, but today leads to Kredarica, the most popular starting point to reach the summit since Jakob Aljaž found a great spot for a hut which was built there in 1896.

However, the Slovenian Mountaineering Society did little for a small group of daring young climbers, who were more interested in new routes than tourist walks on known and secured trails. On Triglav, this meant climbing the Northern Wall, one of the largest of its kind in the Eastern Alps. It's 1300m high (following the German route) and 3500m wide, with several shelves and ravines forming independent walls within the big one. Triglav’s Northern Wall is also home to several of the hardest climbing routes in the Slovenian Alps.

Triglav Northern Wall

Although the first climbers of the Northern Wall were shepherds and hunters, who mostly followed the paths of animals, sports climbing was based on a different kind of logic from that which found a path that was shown to a “gentleman” by a hunter, as the so-called Slovenian route across the Northern Wall was shown by a guide (Komac) to Henrik Tuma in 1910. If the new route for the older generation meant an easier path across a newly climbed slope, the new view on alpinism involved climbing a new, more difficult route without cleared paths and instead with the help of pitons and ropes.

Triglav’s Northern Wall was considered one of the three main problems of the Eastern Alps before it was even climbed, and as such was the focus of German, Austrian and Czech climbers. After the walls of Watzmann (1888) and Hochstadl (1905), the wall of Triglav was finally climbed by three Austrian Germans, Karl Domenigg, Felix Koenig and Hans Reinl, in 1906. The route has become known as the German route, and their success was immediately followed by several failed attempts, some even fatal ones.

Dren Society

In 1908 the Dren society was established, a group of students interested in Alpinism, skiing, caving and photography, novel activities outside the usually promoted Alpine tourism of the Slovenian Mountaineering Society, whose members considered them as “neck-breakers”.

Slovenian Alpinism before World War One was still way behind the developments in other parts of the Alps. The first use of a piton by a Dren member, Pavel Kunaver, is only recorded in 1911, which is also the last year of attempts at the Northern Wall until after the war.

Although Dren members did introduce some novelty into Slovenian climbing, such as winter ascents (sometimes accompanied by skiing) and other more adventurous climbs, their equipment and technique at the time only allowed them to climb routes of the third level of difficulty, and their predecessor and colleague Henrik Tuma hadn’t climbed anything beyond that level either.

This situation can be seen in the fact that the abovementioned German route on the Triglav Northern Wall, which had the climbing difficulty of level IV, was the most difficult route in Slovenian mountains at the time. Hans Reinly, one of the three first climbers described the achievement with the following words: “Triglav rises its triple head angrily. Let it be called Slovenian highest mountain, but this time it was the German force that conquered its most terrifying hip and fought through dark fogs which driven by a storm descent into the depth from the grey ice at the edge of the wall.” Worth mentioning is that in those days there was no meteorological report, and the day and a half climb took place in rain and bad weather.

The guiding ideas of the Dren were to conquer Slovenian mountains before the German mountaineers, try to prevent the Germanisation of Slovenian mountain names, and to climb without mountain guides, which was the main mountaineering style of the time. Lack of manpower and resources prevented these goals being fully achieved, although the ideas persisted throughout the interwar period and became perhaps the main reason behind the increasing Slovenian obsession with Alpinism, which eventually produced some of the best climbers in the world and continues to do so, regardless of the small the size of the place and its population.

Triglav in the Interwar period

After the war, and let’s not forget that one of the bloodiest WWI fronts took place right at Triglav National Park’s eastern border across the banks of the River Soča (the Battle of Isonzo), the main concern of the Slovenian Mountaineering Society was mostly fixing what had been damaged or destroyed.

Furthermore, the Austro-Hungarian Empire fell apart and Slovenia joined the newly formed Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. It turned out, however, that in 1915 the Triple Entente had signed a secret agreement with Italy, promising it large chunks of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in case of victory. With the 1920 Treaty of Rapallo Italy managed to claim most of the lands promised to her by the United Kingdom, Russia and France, which set the Italian-Yugoslav border at the peak of Triglav, a couple of metres away from Aljaž Tower.

Originally, the entire peak of Triglav was to belong to the Kingdom of South Slaves, however, Italy pushed very hard to get the land under its jurisdiction. The dispute was even more meaningful given that it was part of an attempt to extend poor conditions the Slovenes on the other side of the border had to endure in the face of the rising Italian fascism. The negotiations lasted for four years, and while waiting for the final decision certain incidents took place at the top of Triglav, in the summer of 1923 in particular. These are often referred to as “painting battles” but did in fact involve a more serious weapons beside the paintbrushes, which were used to paint Aljaž Tower with slogans and flag colours. Luckily, nobody got hurt, Aljaž Tower was eventually repainted to its original grey, and the final decision on the border in 1924 set the boundary marker 2.55m west from the Aljaž Tower, rendering the summit it effectively Slovenian.

Tourist Club Skala

Within the Slovenian Mountaineering Society (SPD) friction between the moderates and those advocating for “steep tourism” continued into the interwar period. Since the majority of members would not allow sports climbing to be recognised within the SDP, young mountaineers splintered off into a Tourist Club Rock (Turistovski klub Skala, TK Skala) in the winter of 1921.

Rock’s main goal was to continue the development in sports climbing started by Henrik Tuma and evolved by the Dren Society. Among the important climbing achievements of TK Skala are the first Slovenian level V difficulty route climbed by a female climber, Mira Marko Debelak, in 1926 (at the north face of Špik), and the first fully successful winter climb of Triglav’s northern wall in 1939 by Beno Anderwald, Mirko Slapar, Bogdan Jordan and Cene Malovrh, who since 1934, when the SPD finally took alpinism under its wing, had also been members of this organisation.

Foremost, however, Skala’s important achievements also extended into the field of art and culture. Like Dren, TK Skala promoted mountain photography and established a special photography department in charge of postcard production and other images for propaganda purposes. But above all, they were responsible for the first Slovenian feature film, the 1931 V kraljestvu Zlatoroga (In the Kingdom of the Goldhorn) and partially also for the second one a year later, Triglavske Strmine (The Slopes of Triglav). The first movie was produced by Skala and directed by one of their members, Janko Ravnik, while the second was produced by an independent film studio, although it featured several mountaineers/actors from the first film, including Miha Potočnik and Jože Čop.

Fanny Susan Copeland was a remarkable person whose life serves as a curiosity and inspiration. A British woman who was born in Ireland in 1872, grew up in Scotland, and moved to Slovenia in 1921, where she spent most of the rest of her life, dying at 98 in 1970, and buried at the foot of Mount Triglav.

Although she wrote an autobiography it was never published and will remain in copyright limbo until 2020. One person who’s seen this memoir is Eric Percival, whose great-great-great-grandfather, Fred Holloway, knew Fanny’s father, Ralph Copeland, once the Astronomer Royal for Scotland, with the two men meeting near Manchester in the early 1860's. Percival put together the original post that sparked my interest in Ms Copeland, and also kindly supplied some of the pictures that accompany this story. Unless otherwise stated, the facts set out below are also drawn from his account of her life, as based on her own and other reports.

Although British by birth, Fanny was a thoroughly European woman, learning French and German as a child and being educated in Berlin shortly after turning 13. She also learned Latin, Italian, Danish, Norwegian and – due to her father’s interest in the Balkans – Slovenian. This connection with the country would be enough to get our attention, but Ms Copeland holds it because she bucks the standard narrative in terms of when and how one can make a new life for oneself. A brief outline of that life is as follows.

Fanny got married in 1894, at the age of 22, to escape her mother, but her husband was a 36-year old man who she never really liked. The couple had three children and then separated in 1908, finally divorcing in 1912, when Fanny was 40.

She developed a stronger connection with what would eventually become Yugoslavia soon after this, during the First World War, when she supported herself by doing translating for London-based South Slavic organisations. As part of this she translated Bogumil Vošnjak’s Bulwark against Germany: The fight of the Slovenes, the western branch of the Jugoslavs, for national existence, as well as serving as translator for the South Slavic delegation at the Paris Peace Conference.

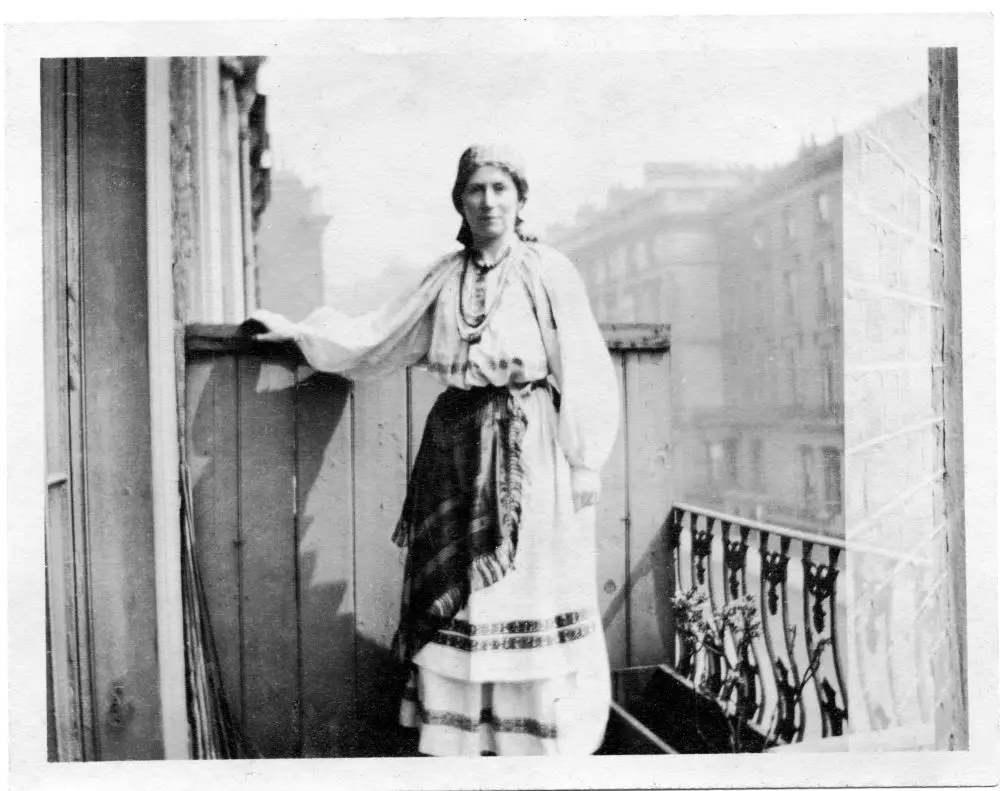

In "traditional costume"

With Oton Župančič at the Congress of Dubrovnik in 1933

Ms Copeland then moved to Ljubljana in 1921, aged 49, when the city was part of the newly formed Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. She was hired as a lecturer in English at the University (which itself only opened in July 1919), a post she held until 1941, when the Germans invaded. At this point, aged 69, she was arrested by the Gestapo and handed to the Italians, who moved her to Trieste, then to Arezzo and finally Bibbiena (in Etruria), where she spent the rest of the war “in open confinement”.

In 1953, aged 81, she finally moved back to Ljubljana. The death of her brother meant that she now had some savings, and thus Fanny Copeland lived in Hotel Slon for the rest of her life, continuing to work as a writer and translator.

Ms Copeland, right, in the Hotel Slon, late 1960s

A pioneer of mountaineering tourism in Slovenia

But Fanny Copeland isn’t just a fine example of a person who didn’t let their gender or age dictate what they should be doing and when, or of someone who managed to successfully integrate themselves into a new country, as she also played a key role in the development of Alpinism as a local tourist offering, and in the promotion of Slovenia as a tourist destination. This section thus draws from an article by Janet Ashton called “Buried at his feet”: Fanny Susan Copeland, Triglav and Slovenia, and from another, Fanny Copeland and the geographical imagination, by Richard Clarke and Marija Anteric, both of which are recommended for more detail.

Ms Copeland felt a great attraction for the Julian Alps, and Slovenia the Slovenes in general, claiming they were the most Scottish of the Yugoslav communities, perhaps because of the mountains, long dominance by other powers, and characteristics of pragmatism and frugality.

She first climbed Triglav in the 1920s, not having taken up serious climbing until her 40s, and did so for the last time in 1958, just before her 87th birthday. She also wrote two books on the Julian Alps, Beautiful Mountains: In the Jugoslav Alps (1931), and A short guide to the Slovene Alps (Jugoslavia) for British and American tourists (1936). As she said in 1957, this was done in the “hope of attracting to Slovenia tourists of all types, from summer visitors in search of little-known beautiful and inexpensive Alpine resorts to Alpinists in search of accessible mountain ranges not yet wholly exploited or explored”.

"Ambassador for the beauty of our mountains". www.gore-ljudje.net

Such efforts to reveal what in those days was still a very hidden gem were not without their obvious dangers, as she noted in a much earlier letter from 1923 when commenting on one of her many trips up Triglav: “It is an interesting walk, but as an expedition it is badly spoilt by the path having been made fool-proof. Result, every holiday is made hideous by hundreds of trippers, and the average person has to wait for a holiday to go up.”

Slovenski planinski muzej:- Fedor Košir, president of the Alpine Association of Slovenia and Fanny Copeland.

As mark of respect for her work to promote the Julian Alps, and to establish Triglav National Park, when Fanny Copeland died her funeral was organised by the Mountaineering Union of Slovenia. She was buried in the cemetery of the village church in Dovje, where you can still see her simple grave, as shown below.

Wikipedia - Miran Hladnik CC-by-2.5

As Copeland wrote in 1931:

By fixed custom those that perish on Triglav are buried at his feet. In the pretty village church of Dovje, opposite the entrance of the stately Valley of the Gate (Vrata– truly a gate to be called Beautiful) they lie side by side. I think they would have it so. The long shadows of the regal avenue of peaks, down which they passed to their last adventure, sweep over their graves as the days and the years roll by; on All Souls’ day the mountaineers bring them pious offerings of prayer and lights, and from their tombstones their names cry greeting and warning to the hosts that go up year by year to visit the mountains, - greeting to the many who go up by the blazed trail where every danger spot is made safe with iron bolt and wire rope, to protect the unwary and put heart into the timid, - greeting to the few who seek, like themselves, to win the goal without guidance save the love of the heights, and no company except the extreme mysteries of life and death – greeting to the cragsman and the lover, to schoolboy and hunter, to smuggler and spy, and the ski-shod friend of the snows….

So if you find yourself in Hotel Slon, on Mount Triglav or by the village of Dovje, spare a thought for the remarkable Fanny Copeland, a woman who not only did as much as anyone else working in English to make the case for a separate Slovenian identity, one distinct from land’s association with the Habsburgs, Slavs and Serbo-Croatians, but also did much to bring the beauty of the land to a wider audience, and to share the best of her adoptive home with the world.

Postscript

As to what life was really like under Tito for a woman born to the academic elite under Queen Victoria, Copeland addresses this at the end of her autobiography, with a postscript to the reader:

But have you really found good reasons to go and live in a ‘communist’ state? This was a question I was often asked soon after my return to Ljubljana. Well - for one thing it depends on what you mean by 'Communism'. If you mean a totalitarian regime then my reply is that no Yugoslav would put up with such a system… The Yugoslavs are stout individualists, but they appreciate law and order. Ask any British tourist who has visited Yugoslavia in recent years.

All our stories on mountaineering in Slovenia can be found here

Last week we came across a photo, as seen here, and ended up learning more about the person behind it, Jerneja Fidler Pompe, or Neja, who runs Exploring Slovenia. This is a site that shares Neja’s love of the mountains in words and photographs, with support from her Instagram page. And in addition to introducing various walks, hikes and climbs in the region, Neja also runs tours enabling you to travel safely and see the best views, as found by experience locals and guides. Always curious and eager to learn more, we got in touch with Neja and asked her some questions, as follows.

How long have you been running Exploring Slovenia?

It’s been three years now. Three years ago, I had this idea to start blogging / vlogging about Slovenian mountains, climbed Mt. Storžič, created a video about the climb (as seen below), opened a channel on YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, and after a month also my blog and Instagram. That’s how it basically all began.

Why? Before following my heart into the mountains, I had been managing a blog and other social media channels for a well-established international IT business for years. I loved my job, I loved blogging, yet somewhat lost the passion for IT, so I decided to finally give something a go I’d always enjoyed.

If readers aren’t familiar with Exploring Slovenia, what does the website try and do, and what are three to five posts that you recommend?

In case you haven’t stumbled upon my blog Exploring Slovenia yet, let me give you a brief idea of what to expect.

Expect various outdoor ideas on what to do in Slovenia, particularly in the Alps, that range from beautiful family hikes, easy, moderate to demanding climbs in the mountains, tips on the best hikes with regard to the season, and, most of all, interesting adventures in the outstanding Slovenian backcountry.

To name a few, my favorite blog posts are the following:

Encircled by high mountains, this picturesque village offers a plethora of hiking trails: Bohinjska Bistrica as it lists quite a number of spectacular hiking ideas in Bohinj Valley, a beautiful glacial valley favored by tourists and locals alike.

Exploring a most beautiful Alpine valley of Slovenia - hiking, climbing and fly-fishing in Logar Valley for holiday ideas in Logar Valley, where I personally note one of the most genuine and memorable experiences in the Slovenian mountains.

When Velika Planina dresses in purple to help you explore an extraordinary wonder at a high-Alpine plateau close to Ljubljana, where every spring endless fields of purple crocuses flood the whole plateau, coloring it purple.

Beautiful Alpine Slovenia in a time-lapse video, where you can watch my 3-minute time-lapse video of the Slovenian mountains - a project that sums over a year-and-a-half worth of videos collected from over a hundred of trails.

Up to Triglav over its North Face and down to the Krma Valley where I take readers on a two-day adventure from one valley to another across Triglav. And of course, there are many more.

What has the experience of running the site taught you?

Probably the most important lesson I learned was to always produce excellent content. Not only in regard to providing the audience great stories, but also taking them through the places I talk about through breathtaking photos and videos. Plus, always to think of new, intriguing adventures not only for proven mountaineers, but also for average hikers that want to simply enjoy the spectacular landscapes Slovenia has to offer.

How important is Instagram to your work?

It’s nice to have it, since I do far more adventures than I have time to blog about. Therefore, most of my hikes are shown only on Instagram, with the very best and most interesting ones also on my blog. It’s a platform that can connect you with your audience in a more personal way, while it also allows you to grow your audience if you approach it the right way.

How long have you been offering tours?

I’ve been always happy to help my readers connect with a mountain guide if they needed one for a certain ascent in certain conditions, but I started offering tours myself last summer. The most popular is Triglav in all seasons and on all routes. It’s the highest mountain in Slovenia, and as such the most obvious choice either when you’re visiting the country for a week or you live there and haven’t found the courage to climb it yet on your own. Nevertheless, Triglav is indeed one of the most fascinating climbs in Slovenia and, must I say, never disappoints, not even those who’ve climbed it several times.

When is the best time of year to climb Triglav, if you’re not a regular climber, and when do you like to climb it?

The easiest time to climb Triglav is when there’s no snow on the way, meaning usually July – September. Even a little bit of snow brings extra hassle and the need to bring extra gear for snow conditions, especially when it’s combined with ice. I prefer climbing it in June, the end of September and October to avoid the crowds. I haven’t climbed it in serious winter conditions yet, when the steel cable is hidden underneath the snow, but I’d love to do that with the help of a mountain guide.

How do you feel about the way tourism is developing in Slovenia?

I love the fact that Slovenia is becoming more recognized in the world and more people are coming to see our wonderful country. In regard to service providers, particularly those working in mountaineering tourism, I like the fact that most of them are well-trained and internationally licensed mountain guides, thus assuring top-level safety and service.

How would you like tourism to develop in the future?

More boutique small groups with respect for our land who visit Slovenia to enjoy incredible landscape, good food, and rich culture, while on the other hand also receive a great service. While I love the fact that the Slovenian mountains are accessible to anyone with the desire to climb them, it would be nice to add more service to the mountain huts for the more demanding guests. I would also love to see more mountain huts open all year round, more options in the food menu, nicer bathrooms with a possibility to shower, heated rooms, etc., which could as well be offered as an extra service as long as it’s available.

Finally, away from hiking and “work”, can you recommend a few things to our readers.

Places: Anything hidden from the main tourist attractions. I really love the Logar Valley for its beautiful landscapes, rivers, waterfalls, and, most of all, welcoming people. While the most memorable experience for me was to fly over the Julian Alps in a hot-air balloon.

Food & drink: Organic herbal tea made of flowers picked in the mountains, roasted lamb and potatoes, beef and mushroom soup, apple strudel, chocolate štruklji (served in the mountain hut Kofce in the Karawanks).

Sports events: Marathon Franja, Goni Pony, and Juriš na Vršič

Books: Čefurji Raus (Vojnović), Alamut (Bartol)

Movies: Gremo mi po svoje and Houston, imamo problem.

Music: Siddharta – Ledena, Napalm 3, Sfinga, Narava; Lamai – Spet te slišim.

You can see more pictures and videos, read more adventures, and maybe even book a tour at Exploring Slovenia; and if you'd like to share your story with our readers, please get in touch at flanner@total-slovenia-news.com

January 22, 2019

It is said that every true Slovene should climb to the top of Triglav, the highest Slovenian mountain, at least once in their lifetime.

However, recent reports of heavy traffic at the top of the mountain along with the trash trail that follows it are evidence that such an expression of national pride doesn’t come without the cost these days. Calls to drop the ‘everyone on Triglav’ idea and replace it with practices that are focused on preservation of nature rather than the defence of territory by repeated conquests of inhabitable lands have been becoming louder in the last two decades. Such a paradigm change is even more pressing since the struggle for independence ended with the final acquisition of the Slovenian statehood in 1991.

This article, however is not about what should be done about mass tourism at the top of Slovenia’s highest peak, but rather how it has all begun. How and why did Triglav and mountaineering in general become so tightly knitted into the fabric of the Slovenian national identity.

The start of an obsession

“To conquer the summit” is in fact a literal translation of a Slovenian expression for reaching the summit (osvojiti vrh), while the very idea of climbing to the top of a mountain instead of worshipping it from the bottom originates in the ideas of the Enlightenment.

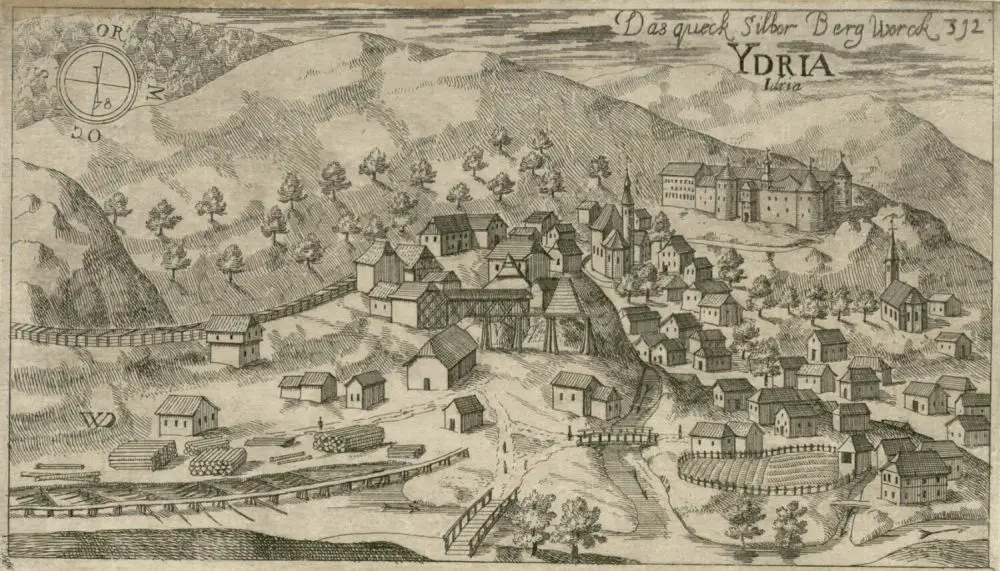

One of the most important places which allowed for the enlightenment to spread among the 18th century Slovenes was, perhaps surprising for some, a secluded mining town called Idrija, the location of the world’s second largest mercury mine. As such, Idrija attracted some of the Europe’s finest natural scientists of the time, in particular Giovanni Antonio Scopoli and Balthasar Hacquet. And both men played an important role in the series of events that lead to the first reaching of Triglav’s summit in 1778, which took place eight years before Mont Blanc, the highest peak in the Alps, was climbed.

Now, Triglav at the time was not Triglav today, equipped with ropes, iron fences and widened trails, and even though the peak lies below three thousand metres, it was quite a difficult mountain to climb, not something one could do on the first attempt. So how did the two enlightened thinkers influence the idea to get to the top?

Scopoli, born in the Southern Tirol (today’s Italy) of the Hapsburg Empire, served in Idrija as the first mine physician between 1754 and 1769, a job which included extensive research on the surrounding botany (no antibiotics in those days), including the Julian Alps, the location of the Triglav massive. This is why Scopoli ended as the first man at the top of Storžič (2,132m) in 1758 and Grintavec (2,558m) in 1759. In 1760 Scopoli published a book on his findings called Flora Carniolica and kept a regular correspondence with no other but the father of contemporary taxonomy, Carl von Linné (aka Carl Linnaeus) in Sweden. The two communicated in Latin.

Apart from his inventory of over 1,100 plants from the Slovenian Northwest, Scopoli also founded an education programme in metallurgy and chemistry in Idrija, which he eventually left for professor’s position at several respectable universities in central Europe.

In Idrija, Scopoli was joined and then replaced by a French surgeon and natural scientist Balthasar Hacquet, who, intrigued by Scopoli’s work, came to Idrija in 1766. Hacquet, also credited with the first description of mercury poisoning symptoms, followed in Scopoli’s steps and attempted his first ascent to Triglav in 1777, but only reached one of the mountain’s lower peaks, Mali Triglav.

The natural sciences and Žiga Zois

At the time Hacquet was also in correspondence with Žiga Zois (Sigmund Zois), a natural science enthusiast, geologist and at the time the richest Slovene, who had just purchased an ironworks facility (fužina) at the foot of the mountain in Bohinj.

Why Sigismund (Žiga) Zois decided to sponsor the first expedition to the top of Triglav in 1778 is not entirely clear, as the so-called Bohinj papers in which expedition details were discussed have been lost. According to one theory, the predominant reasons were to send someone on the lookout for possible new ore deposits. Another theory is that Zois got inspired by the failed attempt of his geologist pen-pal Hacquet. Either way, Žiga Zois presumably promised a financial award to anyone reaching the top and also organised an expedition, which eventually successfully reached the summit for the first time in 1778.

The expedition was led by Zois’ ironworks facility physician and Hacquet’s student Lawrence Willomitzer, who was to be accompanied by three local guides: Luka Korošec and Matevž Kos, both miners and a hunter Štefan Rožič. Although there is some debate about wether or not all of the men really reached the top, in 1978 the Mountaineering Association decided to depict all four men in a statue in Ribčev Laz, Bohinj, as “more first ascents are better than less”.

Vodnik makes it to the top of Slovenia

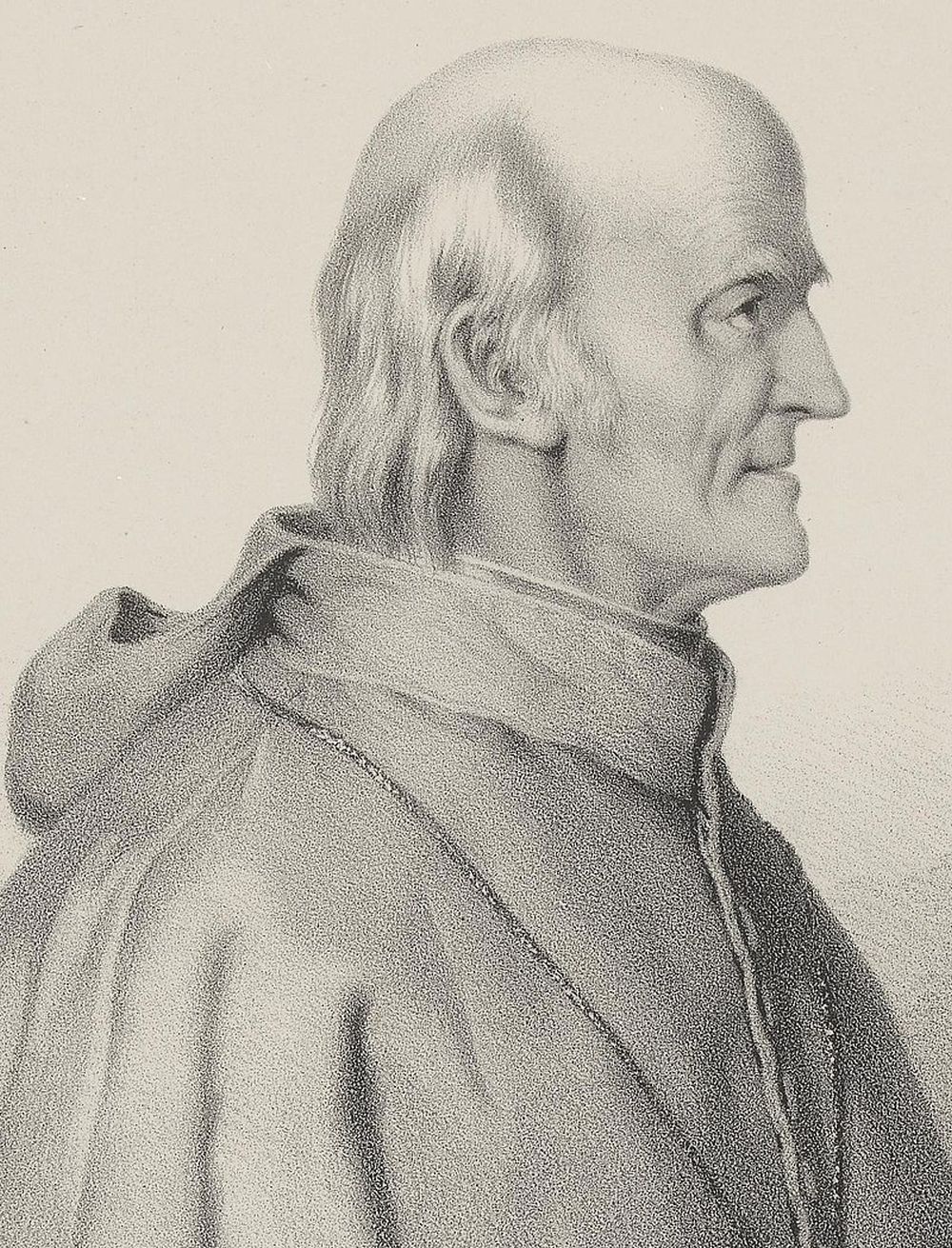

Besides researchers and the nobility (Žiga Zois was a baron), another group of people was interested in mountaineering in those early days: priests.

The first one to mention is Valentin Vodnik from Šiška (Ljubljana), who went to Triglav in 1795 in another of the expeditions financed by Zois. The main goal was to prove the neptunist theory on the sea origin of Julian rocks, and thereby refute the plutonist claims of the rock’s volcanic origin, a dispute Zois found himself in with an acquaintance from Transylvania, Johann Ehrenreich von Fichtel, whose claims on the upper parts of the mountain to be of volcanic origin were based on a simple assumption. To prove Fichtel wrong Zois needed a specimen from the top of the mountain that would show some sediment, which was eventually provided by Vodnik.

Valentin Vodnik, however, didn’t stay priest much longer after meeting Zois in 1792. He switched to teaching position at Ljubljana grammar school six years later. As such, both Vodnik and his patron Zois are part of the group responsible for the early experimentations with Slovenian nationalism, which in the case of Valentin Vodnik meant the use of what was then considered vulgar peasant language in poetry. Indeed, Vodnik’s 1794 ascent of Kredarica and then a year later of Triglav inspired one of his better poems, Vršac.

With Austria’s defeat by the Napoleon’s army, life changed significantly for Vodnik in 1809, when the newly established Illyrian province with its capital set in Ljubljana allowed him to teach in the Slovenian language. He became a principal of Ljubljana grammar school and a supervisor of vocational and handicraft schools. Vodnik marked this French move in support of local ethnic empowerment with an ode called “Illyria reborn” (published in 1811), for which he had to pay a price once the Austrians took their territory back in 1813 – he was banned from ever teaching again in 1815.

Alpinism evolves

In this circle of early priest alpinists we can also count the Dežman brothers, who also reached the top of Triglav in the years of 1808 and 1809. Among Slovenia’s most notable alpine climbers at the time, however, Valentin Stanič stands out as the first proper alpinist in a contemporary sense of the word. His ascents were often unique and daring, since he regularly climbed solo without a guide and even in winter time. He climbed various European mountains, including Grossglockner in 1800. In 1808 he and his guide Anton Kos reached the top of Triglav, where Stanič measured its altitude with a barometric device and only missed the exact figure by 7 metres, an admirable result for an amateur surveyor. Although it seems that his climbing initially served his scientific interests, Stanič later developed a much more sporting interest in trying to climb as many mountains as possible, to be the first one to reach unconquered summits, and on the way overcome hardships and experience happiness and excitement, attitudes that were very unusual and forward-thinking for the era he climbed in.

Despite this, most researchers, noblemen and priests would not head into dangerous mountain conditions without local guides, with this latter group less concerned with getting to the top of the mountain than they were with the opportunity to make some money for themselves and their families.

Enter the Slavs

In the middle of the 19th century several ideological attitudes developed in the mountaineering communities of Europe.

The sporty style of the British nobility on Europe’s most prominent mountains came into being with the help of local French and Swiss guides. This elitist style of climbing by a leisure class who could afford to travel abroad and mount expeditions was contrasted by the style of the Germans, who were climbing at home and thus needed less money to do so, and for whom mountaineering was less associated with class, prestige and conquest. Well, until the Slavs enter the picture.

For most of the Slavs, and especially the Slovenes, mountaineering was closely associated with a defence against language- and class-related Germanising influences, as seen, for example, in the use of new German names for mountains and other places that were originally in Slovenian, a process that increased with the growing number of well-organised German climbing groups who were visiting the Julian Alps at the time. On top of this, Napoleon’s short-lived Illyrian province, which planted the seed of nationalistic sentiment in the minds of the Slovenian masses, strengthened the assimilating pressures of the Austrian empire, which in turn generated much greater resistance. Mountaineering thus became part of the Slovenian national project, and Triglav as the highest peak in the Julian Alps was its symbol.

Read part two here