February 10, 2019

Read part one here and part two here.

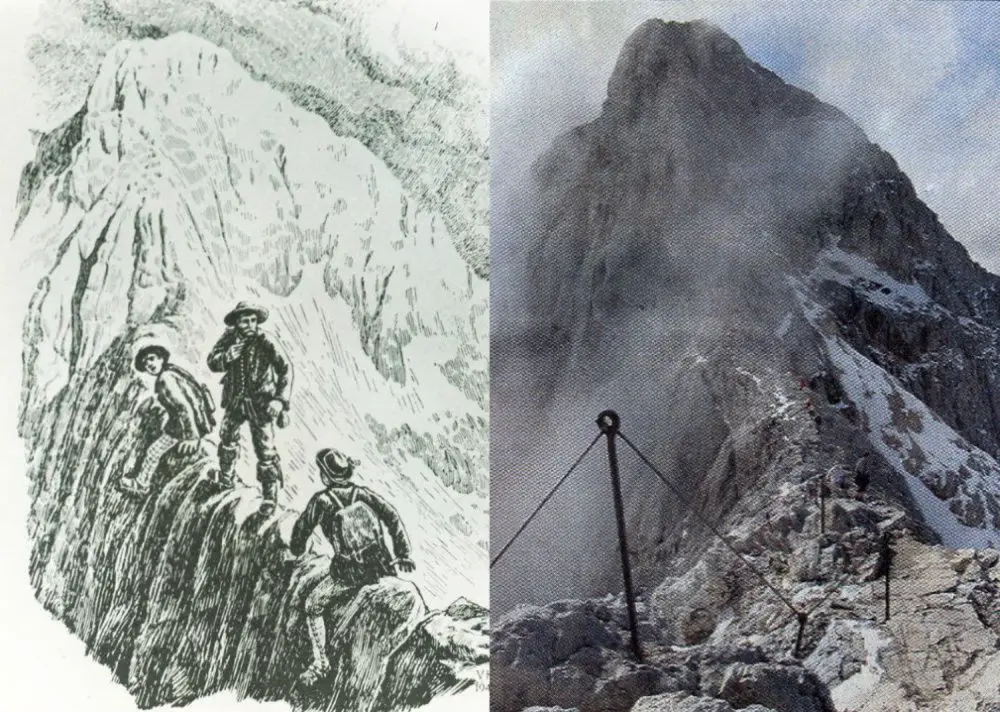

The main task of the Slovenian Mountaineering Society (Slovensko Planinsko Društvo, SDP), established in 1893, was to build, take care and then walk along the secured mountain trails. One of the first important improvements on Triglav was securing some of the most problematic parts of the route leading to the summit. In the early 1870s, a local guide, Šest, and his son eased the trail from Triglav temple to Little Triglav, cut some very much needed steps into the rock, and secured the ridge between both peaks with iron poles with loops that carried a rope fence, which now allowed even more climbers to reach the summit.

In the years that followed, more trails were built and secured, allowing the ascent to the summit from several huts in various directions, including from the north. This is a route which used to cross the shrinking glacier, but today leads to Kredarica, the most popular starting point to reach the summit since Jakob Aljaž found a great spot for a hut which was built there in 1896.

However, the Slovenian Mountaineering Society did little for a small group of daring young climbers, who were more interested in new routes than tourist walks on known and secured trails. On Triglav, this meant climbing the Northern Wall, one of the largest of its kind in the Eastern Alps. It's 1300m high (following the German route) and 3500m wide, with several shelves and ravines forming independent walls within the big one. Triglav’s Northern Wall is also home to several of the hardest climbing routes in the Slovenian Alps.

Triglav Northern Wall

Although the first climbers of the Northern Wall were shepherds and hunters, who mostly followed the paths of animals, sports climbing was based on a different kind of logic from that which found a path that was shown to a “gentleman” by a hunter, as the so-called Slovenian route across the Northern Wall was shown by a guide (Komac) to Henrik Tuma in 1910. If the new route for the older generation meant an easier path across a newly climbed slope, the new view on alpinism involved climbing a new, more difficult route without cleared paths and instead with the help of pitons and ropes.

Triglav’s Northern Wall was considered one of the three main problems of the Eastern Alps before it was even climbed, and as such was the focus of German, Austrian and Czech climbers. After the walls of Watzmann (1888) and Hochstadl (1905), the wall of Triglav was finally climbed by three Austrian Germans, Karl Domenigg, Felix Koenig and Hans Reinl, in 1906. The route has become known as the German route, and their success was immediately followed by several failed attempts, some even fatal ones.

Dren Society

In 1908 the Dren society was established, a group of students interested in Alpinism, skiing, caving and photography, novel activities outside the usually promoted Alpine tourism of the Slovenian Mountaineering Society, whose members considered them as “neck-breakers”.

Slovenian Alpinism before World War One was still way behind the developments in other parts of the Alps. The first use of a piton by a Dren member, Pavel Kunaver, is only recorded in 1911, which is also the last year of attempts at the Northern Wall until after the war.

Although Dren members did introduce some novelty into Slovenian climbing, such as winter ascents (sometimes accompanied by skiing) and other more adventurous climbs, their equipment and technique at the time only allowed them to climb routes of the third level of difficulty, and their predecessor and colleague Henrik Tuma hadn’t climbed anything beyond that level either.

This situation can be seen in the fact that the abovementioned German route on the Triglav Northern Wall, which had the climbing difficulty of level IV, was the most difficult route in Slovenian mountains at the time. Hans Reinly, one of the three first climbers described the achievement with the following words: “Triglav rises its triple head angrily. Let it be called Slovenian highest mountain, but this time it was the German force that conquered its most terrifying hip and fought through dark fogs which driven by a storm descent into the depth from the grey ice at the edge of the wall.” Worth mentioning is that in those days there was no meteorological report, and the day and a half climb took place in rain and bad weather.

The guiding ideas of the Dren were to conquer Slovenian mountains before the German mountaineers, try to prevent the Germanisation of Slovenian mountain names, and to climb without mountain guides, which was the main mountaineering style of the time. Lack of manpower and resources prevented these goals being fully achieved, although the ideas persisted throughout the interwar period and became perhaps the main reason behind the increasing Slovenian obsession with Alpinism, which eventually produced some of the best climbers in the world and continues to do so, regardless of the small the size of the place and its population.

Triglav in the Interwar period

After the war, and let’s not forget that one of the bloodiest WWI fronts took place right at Triglav National Park’s eastern border across the banks of the River Soča (the Battle of Isonzo), the main concern of the Slovenian Mountaineering Society was mostly fixing what had been damaged or destroyed.

Furthermore, the Austro-Hungarian Empire fell apart and Slovenia joined the newly formed Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. It turned out, however, that in 1915 the Triple Entente had signed a secret agreement with Italy, promising it large chunks of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in case of victory. With the 1920 Treaty of Rapallo Italy managed to claim most of the lands promised to her by the United Kingdom, Russia and France, which set the Italian-Yugoslav border at the peak of Triglav, a couple of metres away from Aljaž Tower.

Originally, the entire peak of Triglav was to belong to the Kingdom of South Slaves, however, Italy pushed very hard to get the land under its jurisdiction. The dispute was even more meaningful given that it was part of an attempt to extend poor conditions the Slovenes on the other side of the border had to endure in the face of the rising Italian fascism. The negotiations lasted for four years, and while waiting for the final decision certain incidents took place at the top of Triglav, in the summer of 1923 in particular. These are often referred to as “painting battles” but did in fact involve a more serious weapons beside the paintbrushes, which were used to paint Aljaž Tower with slogans and flag colours. Luckily, nobody got hurt, Aljaž Tower was eventually repainted to its original grey, and the final decision on the border in 1924 set the boundary marker 2.55m west from the Aljaž Tower, rendering the summit it effectively Slovenian.

Tourist Club Skala

Within the Slovenian Mountaineering Society (SPD) friction between the moderates and those advocating for “steep tourism” continued into the interwar period. Since the majority of members would not allow sports climbing to be recognised within the SDP, young mountaineers splintered off into a Tourist Club Rock (Turistovski klub Skala, TK Skala) in the winter of 1921.

Rock’s main goal was to continue the development in sports climbing started by Henrik Tuma and evolved by the Dren Society. Among the important climbing achievements of TK Skala are the first Slovenian level V difficulty route climbed by a female climber, Mira Marko Debelak, in 1926 (at the north face of Špik), and the first fully successful winter climb of Triglav’s northern wall in 1939 by Beno Anderwald, Mirko Slapar, Bogdan Jordan and Cene Malovrh, who since 1934, when the SPD finally took alpinism under its wing, had also been members of this organisation.

Foremost, however, Skala’s important achievements also extended into the field of art and culture. Like Dren, TK Skala promoted mountain photography and established a special photography department in charge of postcard production and other images for propaganda purposes. But above all, they were responsible for the first Slovenian feature film, the 1931 V kraljestvu Zlatoroga (In the Kingdom of the Goldhorn) and partially also for the second one a year later, Triglavske Strmine (The Slopes of Triglav). The first movie was produced by Skala and directed by one of their members, Janko Ravnik, while the second was produced by an independent film studio, although it featured several mountaineers/actors from the first film, including Miha Potočnik and Jože Čop.