Ljubljana related

If you’re a regular reader of TSN, or visitor to Slovenia, you’re no doubt aware of this country’s outsized reputation and achievements with regard to alpinism, a story told in the wonderful Alpine Warriors, which follows the two or three generations of Slovenian climbers who came to prominence in the 1960s to 1990s. These athletes were key players in the dramatic changes overtaking the sport of alpinism as it evolved from a nationalist, state-sponsored activity to a more individual and commercialised one, with documentaries, energy bars and branded jackets, not to mention the opening of Everest to weekend climbers and those in mid-life crises. The same years saw a move from huge, months-long siege-style expedition climbs with dozens of high altitude porters and tons of equipment, to the light and fast style that at its most extreme ends up in solo ascents with only what you can carry in a backpack, up and down mountain in a few days. The idea being that the faster you move, the less danger you’re exposed to in terms of the elements.

One of the names in that book, a controversial one, is Tomo Česen, the father of Aleš Česen, who in August 2018 was part of a Slovenian-British expedition that also featured Luka Stražar and Tom Livingston. The trio became the first to conquer the north face of Latok I (7,145 meters), part of the central Karakoram mountain range in Pakistan, and at the time widely viewed as the most coveted prize in high-altitude climbing. It was a feat that won them the 2019 Piolet d'Or, the top award in mountaineering.

Luckily for armchair adventurers, their ascent was captured on video, with the footage shot by the three climbers, along with Urška Pribošič and Jure Niedorfer, with the latter pair also responsible for editing and post-production work. Even luckier, the whole thing is on Vimeo, and you can see it below.

LATOK 1 from Jure Niedorfer on Vimeo.

September 18, 2019

The Slovenian media reports that Davo Karničar died on Monday in a tree cutting accident near his home in Jezersko.

Davo Karničar was an alpine climber and extreme alpine skier. In 2000 he became the first man ever to ski from the top of Mount Everest.

In his 7 Summits project, he skied from the highest peaks on all seven continents, and in Europe he successfully skied down the northern wall of the Eiger and eastern wall of the Matterhorn.

In the last few years he has focused on becoming the first man to ski down from the top of K2. He was unsuccessful in his 2017 attempt due to bad weather conditions and a back injury.

Davo Karničar was born in 1962 and grew up surrounded by mountains in Zgornje Jezersko.

June 14, 2019

Late snowfalls have delayed the mountaineering season in Slovenia’s high mountains this year, which usually begins mid-June. Anyone headed to high mountains at the moment is advised to bring appropriate winter equipment, or turn around and head down if stumbling upon an icy white surface below a mountain peak.

Accordingly, not all mountain huts have opened their doors to climbers yet. For the current situation on mountain huts please follow this website: https://plangis.pzs.si/?koce=1

Although we seem to be still far from the beginning of the season, the mountain rescue service already intervened 201 times this year and 17 people lost their lives. (source)

Finally, hikers are advised not to greet any helicopters they see by waving to it unless in need of help.

Related: June 16 in Slovenian History: Mountain Rescue Service Established

STA, 23 May 2019 - Two Slovenian mountaineers have completed a series of climbs in remote mountains of Alaska on routes that no human ever set foot on before, conquering three virgin peaks in the process.

Janez Svoljšak and Miha Zupin pioneered five complex new routes in the total length of 4,250 metres in the mountains above the Revelation Glacier between mid-March and mid-April.

The longest and toughest to descend was a 1,300 metre Slovenian route up Apocalypse North, a 2,750 metre peak never climbed before. It took the pair eight hours and a half to climb the mountain.

The expedition was supported by the Slovenian Mountaineering Association, which noted in a press release that the area explored had been visited by one mountaineering expedition a year on average over the past decade, and that the base camp was only accessible by aircraft.

"The area is remote, which means communication is limited to satellite phone messages, and access to the base camp depends on the weather," said Svoljšak, the head of the expedition.

"The weather there is very unsettled, which was hardest during the first few days when the wind bent the poles supporting our tent, and forced us to move on our knees while climbing the ridge."

The strong winds blew large amounts of snow into the face of the mountain, which they had to remove in order to hit the rock or ice, which Svoljšak said was harder than climbing.

Svoljšak, like Zupin member of the Kranj mountaineering section, won the European ice climbing championship title plus a World Cup event in 2016.

The Slovenian Alaska expedition also pioneered the conquest of Four Horsemen East (2,600 m) via a 600 metre East Ridge route, and a peak that they named Wailing Wall (2,450 m).

They also climbed the east face of Golgotha (2,724 m) up a virgin 900 metre route that they named Farther, and Seraph (2,650 m) up a 700 metre new route they christened as The Last Supper for Snow Strugglers.

Slovenia has no shortage of niche events and festivals for those who still enjoy the pleasures of the big screen in public, from Kinodvor’s Film Under the Stars at Ljubljana Castle to the Grossmann Fantastic Film & Wine Festival, which brings horror and honest trash to Ljutomer. However, it’s something that’s occurring next week is that’s perhaps the most Slovenian of all – the Mountain Film Festival (Festival gorniškega filma).

1. Slovenian climbers rock

We’re huge admirers of the past and present of Slovenian climbing here at TSN, be it folks with names like Čop, Kunaver, Zaplotnik, Štremfelj, Prezelj, Karo, or Humar in the Julian Alps, Himalayas, Yosemite and Patagonia, or on the wall in sports climbing with figures such as “the best climber in the world”, the still teenaged Janja Garnbret from Kranj. In short, Slovenia has played and continues to play an outsized role in the world of climbing, with many first ascents and new routes. Learning about it will help draw you closer to the land, and you may even end up on Triglav.

If you want to read more about the history of the scene here, take a look at the book Alpine Warriors.

2. Big screen adventure

So the festival’s got that Slovenian cultural heritage going for it – it’s organised by the Mountain Culture Association (Društvo za gorsko kulturo) and the legendary Silvo Karo – but for me the chief appeal is this: these films will be presented on screens far larger than the ones you have at home. They’re thus are better able to convey the full majesty and terror of the scenes on display (as Aleš Kunaver said, “in the mountains magnificence is diametrically opposed to comfort”).

That movie about the guy who climbed that thing without a rope? Imagine seeing this on something much, much bigger:

3. The programme is world class

The programme looks great, with most of the big mountain features and shorts from the last year or so, and there are also movies on topic adjacent to climbing, like the night sky or environment, so we’ll just present the following convenient selection of trailers, with a lot more to be found at the website.

Cerro Kishtwar - Thomas Huber, Stephan Siegrist and Julian Zankar from Rock & Ice on Vimeo.

Everest Green | Trailer VF from Block 8 Production on Vimeo.

IN THE STARLIGHT - Official Movie Trailer from Mathieu Le Lay on Vimeo.

The Undamaged - Official Trailer from Leeway Collective on Vimeo.

4. A chance to meet the stars

What else can you expect at a mountain film festival in Slovenia? Climbers, and great ones – on the screen, on the stage and in the audience, many of whom live a short drive from the event. Sp Andrej Štremfelj will give a lecture about his ascent of Everest in 1979, when he climbed with the legendary Nejc Zaplotnik, while Aleš Česen and Luka Stražar will be there talking about their ground-breaking ascent, done with Tom Livingstone, of Latok 1 in 2018, “the Holy Grail of high altitude climbing”.

Other names set to talk about their lives and climbs include Rado Kočevar, Hansjörg Aeur, Klemen Bečan and Marija Jeglič. Beyond the Slovenian scene, Colin Haley will be talking about sport alpinism, and one event that’s sure to inspire heated opinions is a roundtable discussion: “Drilling – pitons or bolts?”

5. It’s not just in Ljubljana

While the main events are held in Cankarjev dom, the festival is not confined to the capital. It also has screenings and lectures in Domžale, Celje and Radovljica, while the winning movies will play everywhere (except Celje) at the end of the festival.

You can get a PDF of the programme here

Bonus - the website is ice cool and clean

With a website that's easy to navigate and comes in Slovene and English varieties, letting you search by day, event and venue, the Slovenian Mountain Film Festival offers a perhaps unique chance to see these films on the big screen, with an audience that knows what it’s watching, in a country in love with its mountains.

Related: see all out posts tagged "mountaineering" here

February 10, 2019

Read part one here and part two here.

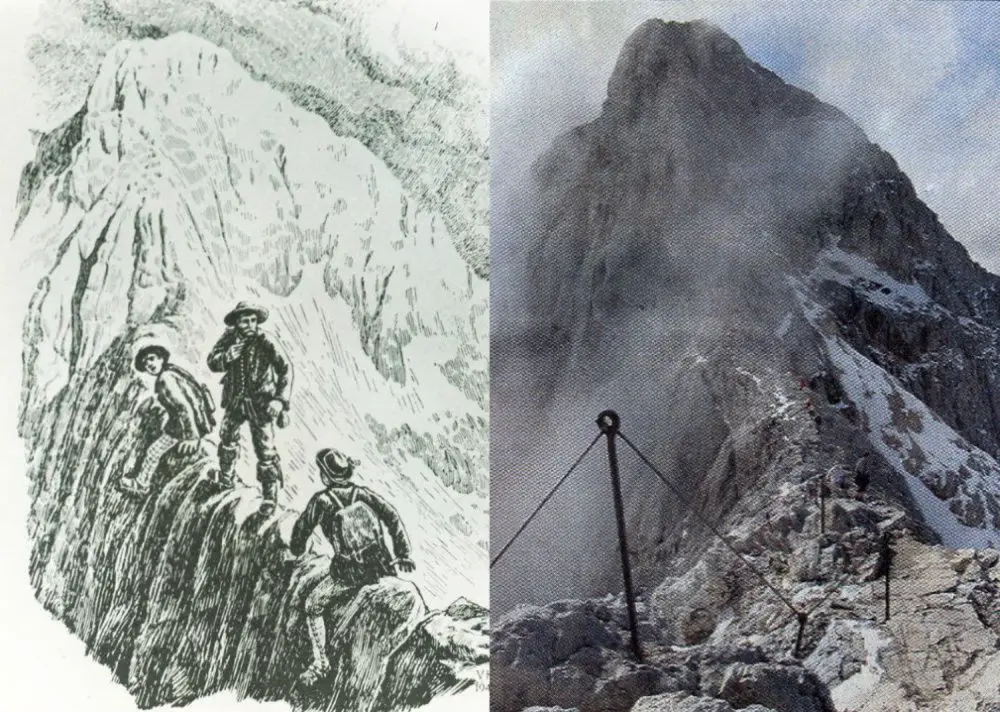

The main task of the Slovenian Mountaineering Society (Slovensko Planinsko Društvo, SDP), established in 1893, was to build, take care and then walk along the secured mountain trails. One of the first important improvements on Triglav was securing some of the most problematic parts of the route leading to the summit. In the early 1870s, a local guide, Šest, and his son eased the trail from Triglav temple to Little Triglav, cut some very much needed steps into the rock, and secured the ridge between both peaks with iron poles with loops that carried a rope fence, which now allowed even more climbers to reach the summit.

In the years that followed, more trails were built and secured, allowing the ascent to the summit from several huts in various directions, including from the north. This is a route which used to cross the shrinking glacier, but today leads to Kredarica, the most popular starting point to reach the summit since Jakob Aljaž found a great spot for a hut which was built there in 1896.

However, the Slovenian Mountaineering Society did little for a small group of daring young climbers, who were more interested in new routes than tourist walks on known and secured trails. On Triglav, this meant climbing the Northern Wall, one of the largest of its kind in the Eastern Alps. It's 1300m high (following the German route) and 3500m wide, with several shelves and ravines forming independent walls within the big one. Triglav’s Northern Wall is also home to several of the hardest climbing routes in the Slovenian Alps.

Triglav Northern Wall

Although the first climbers of the Northern Wall were shepherds and hunters, who mostly followed the paths of animals, sports climbing was based on a different kind of logic from that which found a path that was shown to a “gentleman” by a hunter, as the so-called Slovenian route across the Northern Wall was shown by a guide (Komac) to Henrik Tuma in 1910. If the new route for the older generation meant an easier path across a newly climbed slope, the new view on alpinism involved climbing a new, more difficult route without cleared paths and instead with the help of pitons and ropes.

Triglav’s Northern Wall was considered one of the three main problems of the Eastern Alps before it was even climbed, and as such was the focus of German, Austrian and Czech climbers. After the walls of Watzmann (1888) and Hochstadl (1905), the wall of Triglav was finally climbed by three Austrian Germans, Karl Domenigg, Felix Koenig and Hans Reinl, in 1906. The route has become known as the German route, and their success was immediately followed by several failed attempts, some even fatal ones.

Dren Society

In 1908 the Dren society was established, a group of students interested in Alpinism, skiing, caving and photography, novel activities outside the usually promoted Alpine tourism of the Slovenian Mountaineering Society, whose members considered them as “neck-breakers”.

Slovenian Alpinism before World War One was still way behind the developments in other parts of the Alps. The first use of a piton by a Dren member, Pavel Kunaver, is only recorded in 1911, which is also the last year of attempts at the Northern Wall until after the war.

Although Dren members did introduce some novelty into Slovenian climbing, such as winter ascents (sometimes accompanied by skiing) and other more adventurous climbs, their equipment and technique at the time only allowed them to climb routes of the third level of difficulty, and their predecessor and colleague Henrik Tuma hadn’t climbed anything beyond that level either.

This situation can be seen in the fact that the abovementioned German route on the Triglav Northern Wall, which had the climbing difficulty of level IV, was the most difficult route in Slovenian mountains at the time. Hans Reinly, one of the three first climbers described the achievement with the following words: “Triglav rises its triple head angrily. Let it be called Slovenian highest mountain, but this time it was the German force that conquered its most terrifying hip and fought through dark fogs which driven by a storm descent into the depth from the grey ice at the edge of the wall.” Worth mentioning is that in those days there was no meteorological report, and the day and a half climb took place in rain and bad weather.

The guiding ideas of the Dren were to conquer Slovenian mountains before the German mountaineers, try to prevent the Germanisation of Slovenian mountain names, and to climb without mountain guides, which was the main mountaineering style of the time. Lack of manpower and resources prevented these goals being fully achieved, although the ideas persisted throughout the interwar period and became perhaps the main reason behind the increasing Slovenian obsession with Alpinism, which eventually produced some of the best climbers in the world and continues to do so, regardless of the small the size of the place and its population.

Triglav in the Interwar period

After the war, and let’s not forget that one of the bloodiest WWI fronts took place right at Triglav National Park’s eastern border across the banks of the River Soča (the Battle of Isonzo), the main concern of the Slovenian Mountaineering Society was mostly fixing what had been damaged or destroyed.

Furthermore, the Austro-Hungarian Empire fell apart and Slovenia joined the newly formed Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. It turned out, however, that in 1915 the Triple Entente had signed a secret agreement with Italy, promising it large chunks of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in case of victory. With the 1920 Treaty of Rapallo Italy managed to claim most of the lands promised to her by the United Kingdom, Russia and France, which set the Italian-Yugoslav border at the peak of Triglav, a couple of metres away from Aljaž Tower.

Originally, the entire peak of Triglav was to belong to the Kingdom of South Slaves, however, Italy pushed very hard to get the land under its jurisdiction. The dispute was even more meaningful given that it was part of an attempt to extend poor conditions the Slovenes on the other side of the border had to endure in the face of the rising Italian fascism. The negotiations lasted for four years, and while waiting for the final decision certain incidents took place at the top of Triglav, in the summer of 1923 in particular. These are often referred to as “painting battles” but did in fact involve a more serious weapons beside the paintbrushes, which were used to paint Aljaž Tower with slogans and flag colours. Luckily, nobody got hurt, Aljaž Tower was eventually repainted to its original grey, and the final decision on the border in 1924 set the boundary marker 2.55m west from the Aljaž Tower, rendering the summit it effectively Slovenian.

Tourist Club Skala

Within the Slovenian Mountaineering Society (SPD) friction between the moderates and those advocating for “steep tourism” continued into the interwar period. Since the majority of members would not allow sports climbing to be recognised within the SDP, young mountaineers splintered off into a Tourist Club Rock (Turistovski klub Skala, TK Skala) in the winter of 1921.

Rock’s main goal was to continue the development in sports climbing started by Henrik Tuma and evolved by the Dren Society. Among the important climbing achievements of TK Skala are the first Slovenian level V difficulty route climbed by a female climber, Mira Marko Debelak, in 1926 (at the north face of Špik), and the first fully successful winter climb of Triglav’s northern wall in 1939 by Beno Anderwald, Mirko Slapar, Bogdan Jordan and Cene Malovrh, who since 1934, when the SPD finally took alpinism under its wing, had also been members of this organisation.

Foremost, however, Skala’s important achievements also extended into the field of art and culture. Like Dren, TK Skala promoted mountain photography and established a special photography department in charge of postcard production and other images for propaganda purposes. But above all, they were responsible for the first Slovenian feature film, the 1931 V kraljestvu Zlatoroga (In the Kingdom of the Goldhorn) and partially also for the second one a year later, Triglavske Strmine (The Slopes of Triglav). The first movie was produced by Skala and directed by one of their members, Janko Ravnik, while the second was produced by an independent film studio, although it featured several mountaineers/actors from the first film, including Miha Potočnik and Jože Čop.

January 28, 2019

Read part one here.

If the first mountaineering successes took place in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the second half of the latter saw the emergence of mountaineering organisations, which built mountain huts, marked and maintained trails, and brought mountaineering closer to the broader public.

Friends of Triglav

On Triglav, the first mountain hut (called Triglav Temple) was built in 1869 by Jože Škantar at the initiative of the local chaplain, Ivan Žan. The hut was part of the plan to establish the first Slovenian mountaineering organisation by some of the locals of Bohinj, who also sought to register the first Slovenian alpinist club, Friends of Triglav, in 1872. Unfortunately, just as the authorities returned the papers, demanding a change in the place of registration from ‘Bohinj’ to one of the villages in the area, Ivan Žan was transferred from Bohinj to Škofja Loka, and the six-day deadline to fix the problem was missed.

The aforementioned Triglav temple, a simple wooden hut, standing at the elevation of 2,401 metres, managed to defy the devastating forces of nature for about five years. Then, in 1877, Jože Škantar together with his son erected another, much stronger building, which was taken over by the merged German and Austrian climbing clubs (Deutscher und Österreichischer Alpenverein, DÖAV), and therefore also carried a German name, that is, Triglav Hütte. In 1911 Triglav Hütte became a property of the Austrian Tourist Club, which changed its name to Maria Theresien Haus and enlarged into its current size. The building changed its name again in between the World Wars, when it was called the Alexander hut. Only after the Second World War did the hut finally got its currently neutral name, Dom Planika (Edelweiss hut).

Pipe club and the Slovenian Mountaineering Society

Two decades passed before another attempt at a Slovenian mountaineering society (Slovensko planinsko društvo, SPD), which was finally formed in 1893. Meanwhile, trails and huts in the mountains were built and maintained by German and Austrian clubs for German and Austrian mountaineers.

In 1892, six Slovenian mountaineers from Ljubljana met at the Rožnik restaurant at the top of the Ljubljana hill with the same name, where they founded an informal club called Pipa (Pipe), since one of the many rules, most of them hardly to be taken seriously, was that all of its members had to be equipped with pipes, tobacco and matches, along the rule that members had to visit one of Slovenia’s mountains every Sunday, or at least walk to the top of Rožnik. They also put together a single copy of one issue of a newspaper with jokes and mountaineering stories, which was kept at the Rožnik restaurant for its members to read free of charge, while other visitors had to pay in order to do so.

On one of their trips, Pipa members discussed the problem of German domination of their activity in the Slovenian mountains, which eventually resulted in the Slovenian mountaineering society, or Slovensko Planinsko Društvo (SPD hereafter), which was formally established in 1893 in Ljubljana. Numerous branches of this society emerged in other parts of the country in the years to follow, including its Radovljica branch in 1895, where one of the constitutive members was also a local priest – Jakob Aljaž, a name that still lives on the summit.

Jakob Aljaž

SPD begun marking the mountain trails and building its own huts, which Germans called huts of defiance, since they were often built just a few metres away from the German ones. From this defiance came the idea of Jakob Aljaž to purchase the top of Triglav and decorate it with a tower which would eventually bear the first writing in the Slovenian language in the entire Triglav massif area: Aljažev stolp.

The tower was designed by Aljaž himself, and manufactured by his friend, tinsmith Anton Belec from Šentvid (Ljubljana) in 1895. The tower was a metal cylinder with a metal flag bearing the year of its construction stuck to the top.

Parts were taken by train to Mojstrana and carried to the top of Triglav by a group of six strong men over a span of one week. It was then to be put together by Aljaž, Belec and three assistants. On the night of their final climb to the mountain the five rested in Deschmannhaus, one of the three huts on Triglav at the time, all run by the Carniolan section of the DÖAV, which fought against any bilingual signs on the mountain and also prioritised German climbers over Slovenian ones when they were looking for shelter in their mountain huts.

However, foggy weather cleared the mountain, which meant that the group could work at the top without being disturbed by potentially outraged bystanders. The fog, however, also meant that Aljaž decided not to climb to the summit but rather to “supervise” the construction from below by listening to the sounds of the hammers hitting brass. The tower was standing after about five hours of such work.

Once the tower was discovered the DÖAV was enraged and demanded its removal in a legal battle that was based on a claim that Aljaž had destroyed a triangulation point, which allegedly stood at the tower’s location. Aljaž on the other hand claimed that no such trig point was ever in the tower’s location, apart from a wooden pyramid which had been placed at the top 40 years earlier and destroyed by weather long before the tower was erected. His claims were eventually confirmed by a key witness, Captain Schwartz, who later asked Aljaž to allow a trig point’s information pergament to be placed under the tower, carrying information about its coordinates and the elevation point of its top, which effectively brought the tower under the Emperor’s protection. Later on Aljaž donated the tower to the SDP.

With the tower also came a song, which became the SDP’s official anthem. In 1894 a poem Slavin, written by Matija Zemljič, caught Jakob Aljaž’s eye, so he wrote music for it after which it became known as Oj, Triglav, moj dom. It has since been adopted as the official anthem of the Slovenian Mountaineering Association, and also serves as a basis for the fanfares starting and ending the Ski Jumping FIS Finals in Planica.

With the tower at the top Triglav thus became the main symbol of the Slovenian national identity.

Meanwhile, a struggle of another kind had emerged. SDP and its touristic culture of walking to the top of a mountain became too small to accommodate the emerging new culture of alpinism within one group. The peak of Triglav may have been conquered, but the battle for domination now opened at the mountain’s northern face, also known as Triglav’s northern wall.

Read part three here

January 22, 2019

It is said that every true Slovene should climb to the top of Triglav, the highest Slovenian mountain, at least once in their lifetime.

However, recent reports of heavy traffic at the top of the mountain along with the trash trail that follows it are evidence that such an expression of national pride doesn’t come without the cost these days. Calls to drop the ‘everyone on Triglav’ idea and replace it with practices that are focused on preservation of nature rather than the defence of territory by repeated conquests of inhabitable lands have been becoming louder in the last two decades. Such a paradigm change is even more pressing since the struggle for independence ended with the final acquisition of the Slovenian statehood in 1991.

This article, however is not about what should be done about mass tourism at the top of Slovenia’s highest peak, but rather how it has all begun. How and why did Triglav and mountaineering in general become so tightly knitted into the fabric of the Slovenian national identity.

The start of an obsession

“To conquer the summit” is in fact a literal translation of a Slovenian expression for reaching the summit (osvojiti vrh), while the very idea of climbing to the top of a mountain instead of worshipping it from the bottom originates in the ideas of the Enlightenment.

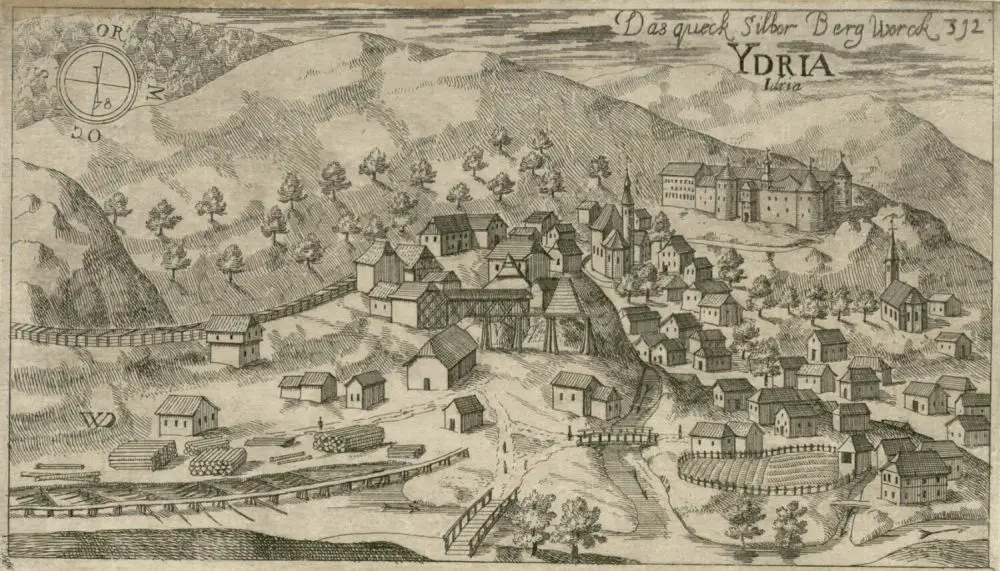

One of the most important places which allowed for the enlightenment to spread among the 18th century Slovenes was, perhaps surprising for some, a secluded mining town called Idrija, the location of the world’s second largest mercury mine. As such, Idrija attracted some of the Europe’s finest natural scientists of the time, in particular Giovanni Antonio Scopoli and Balthasar Hacquet. And both men played an important role in the series of events that lead to the first reaching of Triglav’s summit in 1778, which took place eight years before Mont Blanc, the highest peak in the Alps, was climbed.

Now, Triglav at the time was not Triglav today, equipped with ropes, iron fences and widened trails, and even though the peak lies below three thousand metres, it was quite a difficult mountain to climb, not something one could do on the first attempt. So how did the two enlightened thinkers influence the idea to get to the top?

Scopoli, born in the Southern Tirol (today’s Italy) of the Hapsburg Empire, served in Idrija as the first mine physician between 1754 and 1769, a job which included extensive research on the surrounding botany (no antibiotics in those days), including the Julian Alps, the location of the Triglav massive. This is why Scopoli ended as the first man at the top of Storžič (2,132m) in 1758 and Grintavec (2,558m) in 1759. In 1760 Scopoli published a book on his findings called Flora Carniolica and kept a regular correspondence with no other but the father of contemporary taxonomy, Carl von Linné (aka Carl Linnaeus) in Sweden. The two communicated in Latin.

Apart from his inventory of over 1,100 plants from the Slovenian Northwest, Scopoli also founded an education programme in metallurgy and chemistry in Idrija, which he eventually left for professor’s position at several respectable universities in central Europe.

In Idrija, Scopoli was joined and then replaced by a French surgeon and natural scientist Balthasar Hacquet, who, intrigued by Scopoli’s work, came to Idrija in 1766. Hacquet, also credited with the first description of mercury poisoning symptoms, followed in Scopoli’s steps and attempted his first ascent to Triglav in 1777, but only reached one of the mountain’s lower peaks, Mali Triglav.

The natural sciences and Žiga Zois

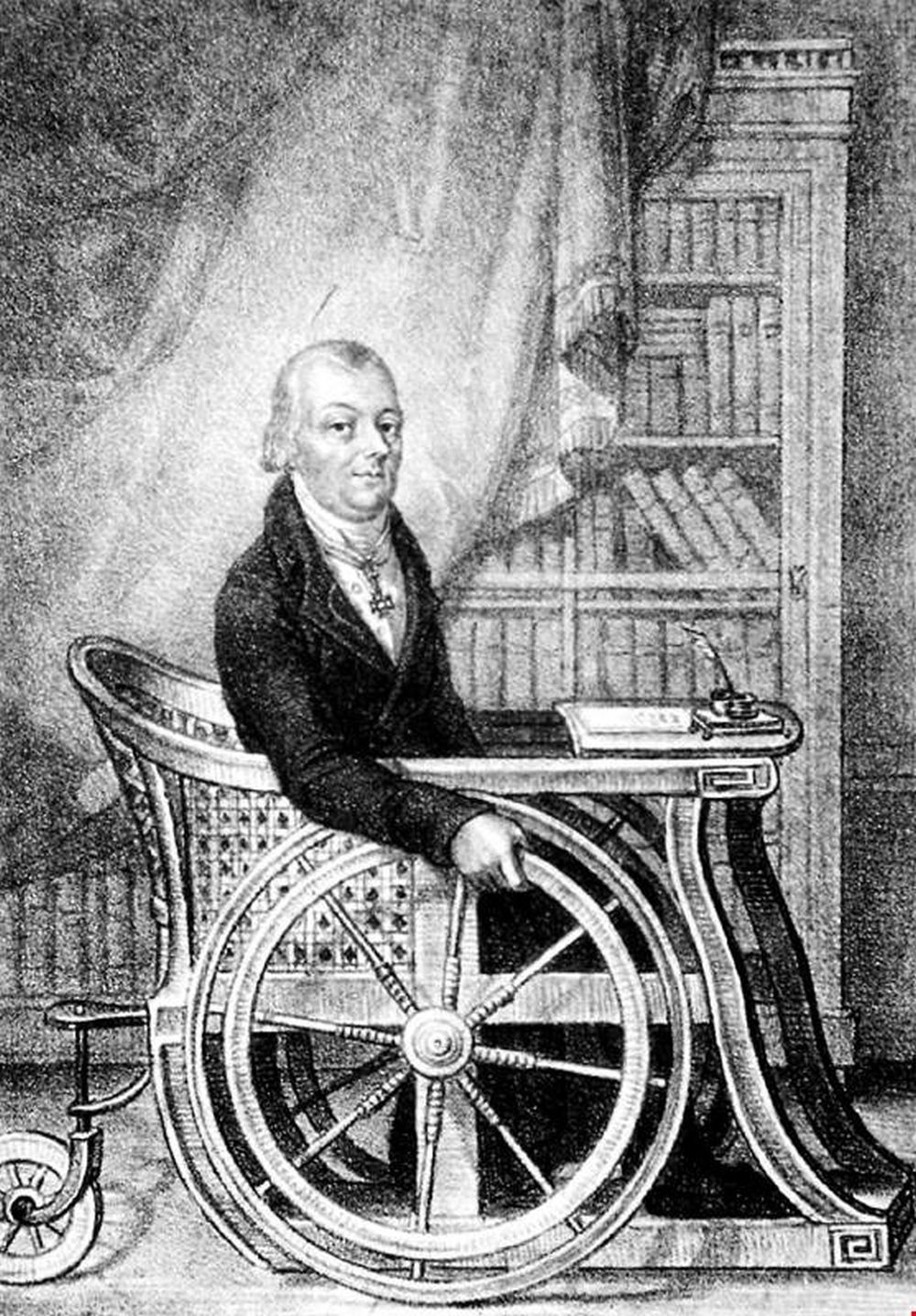

At the time Hacquet was also in correspondence with Žiga Zois (Sigmund Zois), a natural science enthusiast, geologist and at the time the richest Slovene, who had just purchased an ironworks facility (fužina) at the foot of the mountain in Bohinj.

Why Sigismund (Žiga) Zois decided to sponsor the first expedition to the top of Triglav in 1778 is not entirely clear, as the so-called Bohinj papers in which expedition details were discussed have been lost. According to one theory, the predominant reasons were to send someone on the lookout for possible new ore deposits. Another theory is that Zois got inspired by the failed attempt of his geologist pen-pal Hacquet. Either way, Žiga Zois presumably promised a financial award to anyone reaching the top and also organised an expedition, which eventually successfully reached the summit for the first time in 1778.

The expedition was led by Zois’ ironworks facility physician and Hacquet’s student Lawrence Willomitzer, who was to be accompanied by three local guides: Luka Korošec and Matevž Kos, both miners and a hunter Štefan Rožič. Although there is some debate about wether or not all of the men really reached the top, in 1978 the Mountaineering Association decided to depict all four men in a statue in Ribčev Laz, Bohinj, as “more first ascents are better than less”.

Vodnik makes it to the top of Slovenia

Besides researchers and the nobility (Žiga Zois was a baron), another group of people was interested in mountaineering in those early days: priests.

The first one to mention is Valentin Vodnik from Šiška (Ljubljana), who went to Triglav in 1795 in another of the expeditions financed by Zois. The main goal was to prove the neptunist theory on the sea origin of Julian rocks, and thereby refute the plutonist claims of the rock’s volcanic origin, a dispute Zois found himself in with an acquaintance from Transylvania, Johann Ehrenreich von Fichtel, whose claims on the upper parts of the mountain to be of volcanic origin were based on a simple assumption. To prove Fichtel wrong Zois needed a specimen from the top of the mountain that would show some sediment, which was eventually provided by Vodnik.

Valentin Vodnik, however, didn’t stay priest much longer after meeting Zois in 1792. He switched to teaching position at Ljubljana grammar school six years later. As such, both Vodnik and his patron Zois are part of the group responsible for the early experimentations with Slovenian nationalism, which in the case of Valentin Vodnik meant the use of what was then considered vulgar peasant language in poetry. Indeed, Vodnik’s 1794 ascent of Kredarica and then a year later of Triglav inspired one of his better poems, Vršac.

With Austria’s defeat by the Napoleon’s army, life changed significantly for Vodnik in 1809, when the newly established Illyrian province with its capital set in Ljubljana allowed him to teach in the Slovenian language. He became a principal of Ljubljana grammar school and a supervisor of vocational and handicraft schools. Vodnik marked this French move in support of local ethnic empowerment with an ode called “Illyria reborn” (published in 1811), for which he had to pay a price once the Austrians took their territory back in 1813 – he was banned from ever teaching again in 1815.

Alpinism evolves

In this circle of early priest alpinists we can also count the Dežman brothers, who also reached the top of Triglav in the years of 1808 and 1809. Among Slovenia’s most notable alpine climbers at the time, however, Valentin Stanič stands out as the first proper alpinist in a contemporary sense of the word. His ascents were often unique and daring, since he regularly climbed solo without a guide and even in winter time. He climbed various European mountains, including Grossglockner in 1800. In 1808 he and his guide Anton Kos reached the top of Triglav, where Stanič measured its altitude with a barometric device and only missed the exact figure by 7 metres, an admirable result for an amateur surveyor. Although it seems that his climbing initially served his scientific interests, Stanič later developed a much more sporting interest in trying to climb as many mountains as possible, to be the first one to reach unconquered summits, and on the way overcome hardships and experience happiness and excitement, attitudes that were very unusual and forward-thinking for the era he climbed in.

Despite this, most researchers, noblemen and priests would not head into dangerous mountain conditions without local guides, with this latter group less concerned with getting to the top of the mountain than they were with the opportunity to make some money for themselves and their families.

Enter the Slavs

In the middle of the 19th century several ideological attitudes developed in the mountaineering communities of Europe.

The sporty style of the British nobility on Europe’s most prominent mountains came into being with the help of local French and Swiss guides. This elitist style of climbing by a leisure class who could afford to travel abroad and mount expeditions was contrasted by the style of the Germans, who were climbing at home and thus needed less money to do so, and for whom mountaineering was less associated with class, prestige and conquest. Well, until the Slavs enter the picture.

For most of the Slavs, and especially the Slovenes, mountaineering was closely associated with a defence against language- and class-related Germanising influences, as seen, for example, in the use of new German names for mountains and other places that were originally in Slovenian, a process that increased with the growing number of well-organised German climbing groups who were visiting the Julian Alps at the time. On top of this, Napoleon’s short-lived Illyrian province, which planted the seed of nationalistic sentiment in the minds of the Slovenian masses, strengthened the assimilating pressures of the Austrian empire, which in turn generated much greater resistance. Mountaineering thus became part of the Slovenian national project, and Triglav as the highest peak in the Julian Alps was its symbol.

Read part two here

“A fire burned inside me and I knew only two ways out: either to keep stoking it or allow myself to be burned by it.” Nejc Zaplotink, Pot

There are many moments of horror when reading Bernadette McDonald’s Alpine Warriors (2015). The horror of snow, ice and wind to contend with, along with vertical walls, overhangs, collapsing seracs, avalanches, frostbite, lost shoes, exploding stoves, and death. And there is, as in every climbing book, death aplenty, the narrative always taking an ominous turn when recollections slip away and it becomes clear the climber in question never got to tell his side of the story from this point on, that they disappeared into the snow.

Alpine Warriors, a follow-up to McDonald’s 2008 book on Tomaž Humar, tells the story of two or three generations of Slovenian climbers who came to prominence in the 1960s to 1990s. This small group made many first ascents and established new routes up the most difficult faces. They were also key players in the dramatic changes overtaking the sport of alpinism as it evolved from a nationalist, state-sponsored activity to a more individual and commercialised one, with documentaries, energy bars and branded jackets, not to mention the opening of Everest to weekend climbers and those in mid-life crises. The same years saw a move from huge, months-long siege-style expedition climbs with dozens of high altitude porters and tons of equipment, to the light and fast style that at its most extreme ends up in solo ascents with only what you can carry in a backpack, up and down mountain in a few days.

The latter, exemplified in the book by the likes of Tomo Česen (b. 1959, Kranj) and Tomaž Humar (b. 1969 Ljubljana, d. 2009 Nepal), may seem more dangerous to non-climbing readers, but there’s a logic to it. The faster you move, the less danger you’re exposed to in terms of the elements. Think of camping out on the face of a mountain as like playing Russian roulette, and each day, as the sun warms the face, there are avalanches, sometimes lasting for hours, meaning in some places there’s only four hours of safe climbing, during which you need to make some ground and then dig a snow cave before the weather turns. The book is thus full of extreme events, amazing escapes and tales of endurance that appear superhuman. And despite all the skills of the climbers, and all their good judgement and experience, sometimes people just vanish, overwhelmed by the forces of nature, and other times they make it down, frostbitten and exhausted, having survived through the luck of the draw.

Manaslu - Konec poti Nejca Zaplotnika from Anže Čokl on Vimeo.

McDonald picks Nejc Zaplotnik (b. 1952 Kranj, d. 1983 Nepal) as the thread that runs through this group of climbers, who either knew the man or grew up hearing about him, not least through his book Pot. Despite its lasting success in Slovenia this work remains untranslated, but the title means “the Path” or, in a more Daoist sense, “the Way”, and the excerpts in Alpine Warriors set out a philosophy of climbing and being in the mountains that’s very tempting if divorced from the realities of life at 8,000 metres – “A path leads nowhere but on to the next path. And that one takes you to the next crossroads. Without end.”

The story begins in 1960, with the first Yugoslav team being sent to the Himalayas as part of a state-funded expedition, with the bulk of the talent coming from Slovenia. As McDonald notes, “the topography, combined with the hard-working, pious, matter-of-fact Slovenian temperament, honed and perfected under German/Austrian domination, created the perfect climbing machines.”

One side the of the narrative thus follows the changes in Slovenian society from the simplicity and relative poverty of the 1960s and 70s, when just leaving the country with visas and enough equipment was a trial, to the more open and individualistic 80s, 90s and beyond, when media interest and commercial sponsorship gave climbers more options than following the dictates of the Alpine Association. As McDonald tells it, the Association, as a nationalist endeavour, remained focused on goals such as climbing all 14 eight-thousanders, while the climbers themselves often had their own ambitions, like finding new routes up challenging faces, no matter what the height or where their partners came from (with, for example, Marko Prezelj forging a long partnership with the American Steve House - as seen in the following documentary, along with Vince Anderson).

Within this setting McDonald sets up various the personality conflicts, making clear there’s not one type of climber, even at the highest levels. Zaplotnik is thus presented as the romantic mystic, Silvo Karo (b. 1960 Ljubljana) and Marko Prezelj (b. 1965 Kamnik) as taciturn and plain-spoken (the latter on Kangchenjunga “At first it looks shit, and then you begin to solve the problems. Without complexity I am not challenged.”) and Tomaž Humar as an unstable, driven man, pushing himself into a public role and then retreating from it, eventually dying alone at the top of a mountain after his life at base level seemed to have fallen apart.

There are many scenes when even the most imaginative reader will struggle to feel what it’s like to experience 200 km per hour gusts of wind or -36°C while trying to bivouac on a ledge “three butt cheeks wide”, or to find your tent has been crushed by snow, equipment lost, ice axe shattered, partner vanished, with no hope of rescue but a will to live and endure that might not be enough. These are extraordinary men (and a few women), the kind who can say, like Tomo Česen,“I knew…that I could go three to four days without food and two or more days without sleep”.

Česen himself is presented as a pivotal figure, both for his early acceptance of sponsorship as a way of breaking free of the Alpine Association, and for the scandals related to claimed ascents of Jannu and Lhotse’s South Face, which suggest how commercial pressures changed the nature of the sport, demanding ever-greater spectacles, leading to the circus that often surrounded McDonald’s last focal climber, Tomaž Humar.

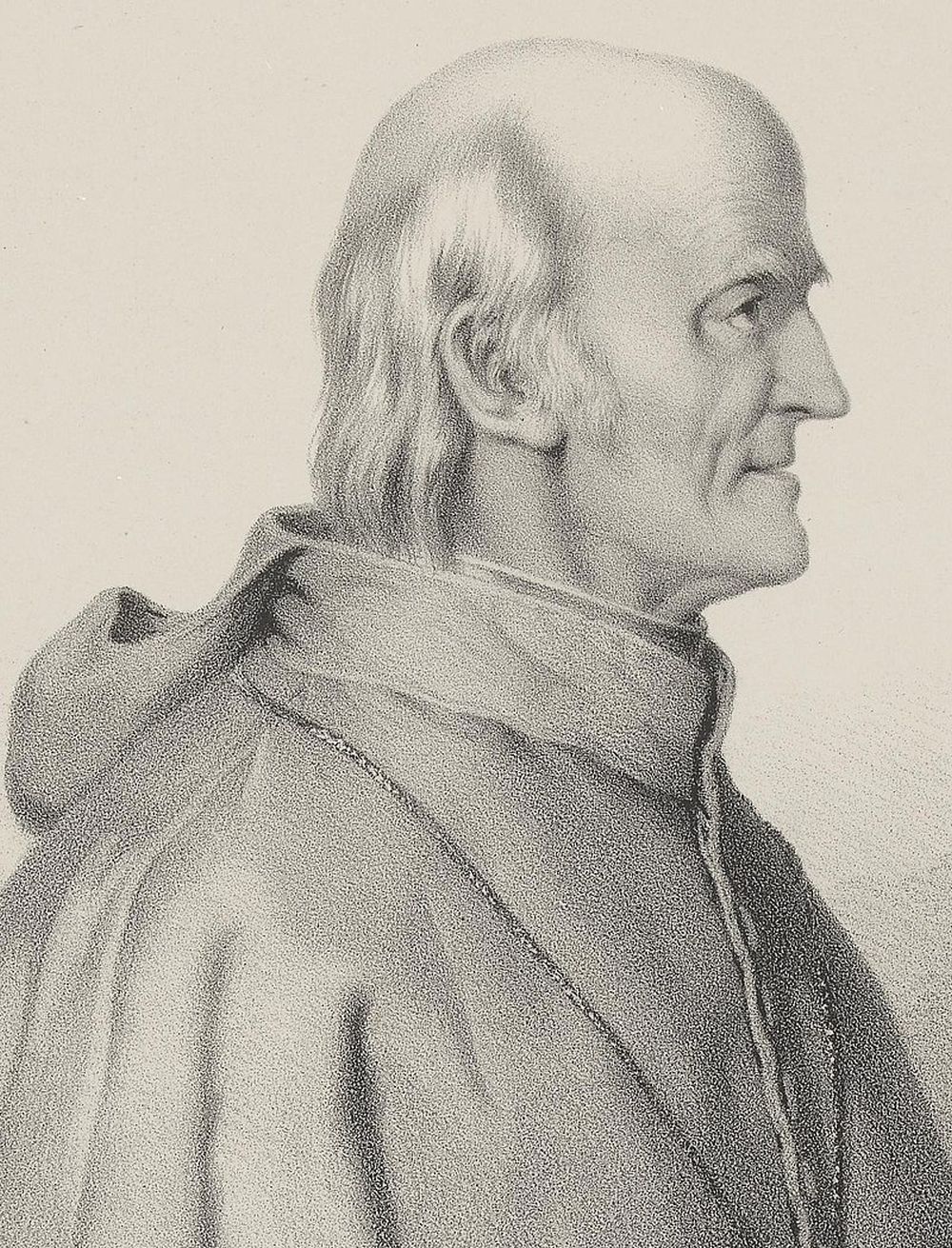

Others covered in the book include Tone Škarja (b. 1937 Lubljana), Stane Belak-Šrauf (b. 1940 Ljubljana, d. 1995 Mojstrovka, avalanche), Marjan Manfreda (b. 1950 Bohinjska bela, d. 2015 Gorenjska, traffic accident), Stipe Božič (b. 1951 Croatia), Drago Bregar (b. 1952 Višnja Gora, d. 1977 Pakistan), Viki Grošelj (b. 1952 Ljubljana), Borut Bergant (b. 1954 Podljubelj, d. 1985 Nepal), Franček Knez (b. 1955 Celje, d. 2017 while climbing in Slovenia), Andrej Štremfelj (b. 1956 Kranj), Slavko Svetičič (b. 1958 Šebrelje, d. 1995 Pakistan) Janez Jeglič (b. 1961 Tuhinjska dolina, d. 1997 Nepal), and Vanja Furlan (b. 1966 Novo mesto, d. 1996 Mojstrovka). There are thus too many interesting characters here for this review to touch them all, but one we’ll highlight is Aleš Kunaver (b. 1935 Ljubljana, d. 1984 Jesenice, helicopter accident), the team leader on many expeditions who was able to bring out the best in his climbers while remaining in the shadows and often off the summit. It was also Kunaver who opened the first school for Sherpas in 1979, in order to reduce accidents in the Himalayas, and from whom we get the quote “In the mountains magnificence is diametrically opposed to comfort”.

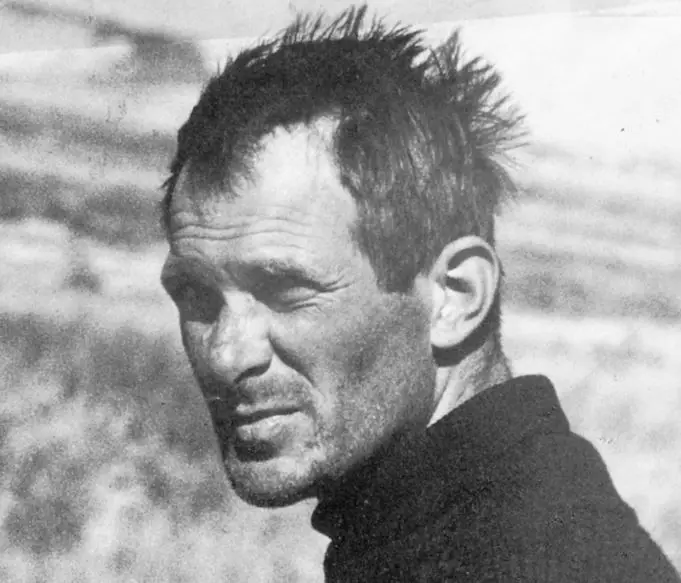

Aleš Kunaver. Source:

And while there are deaths throughout the book many of the characters are still alive and active on the scene, firmly enmeshed in the both the history and present of alpinism and climbing in general, not just in a Slovenian context, but globally. The move from high to steep mountains, to walls with more technical difficulty than altitude, can be seen in pop culture triumphs like Alex Honnold’s free solo of El Capitan, as well as less publicised ascents such as that of the North Face of Latok, the “holy grail” of high altitude climbing that was finally achieved in summer 2018 by a Slovene-British expedition consisting of Aleš Česen (Tomo’s son), Luka Stražar and Tom Livingston (as reported here).

So although the book Alpine Warriors was published in 2015, and ends with Humar’s death, the story continues, and is one that those of us who live in Slovenia can easily feel a personal connection to, through the men and women who live among us when not climbing, and through the stunning landscape that has shaped such people and inspired dreams of the freedom that’s possible when one leaves the towns and cities and goes up into the mountains with good friends or alone.

In short, I enjoyed this book a lot, and if any of the above struck your interest then consider picking up a copy of Alpine Warriors, by Bernadette McDonald, and learning much more about Slovenia’s climbers. I’ve seen both English and Slovene editions in bookstores here, and it can also be ordered online in paper or ebook versions.

We got Bernadette McDonald’s Alpine Warriors for Christmas, a book that recounts the history of Slovene alpinism from the 1970s on. It’s a fascinating tale, one that we’ll be reviewing here soon, and as part of the reading process it’s been necessary to go online and check out photographs, videos and maps to get some idea of what this generation or two of climbers achieved, when a few individuals from a small and relatively impoverished country opened up new routes and conquered new faces, driven by an inner fire to continue through terrible conditions with minimal support, and often paying the highest price for their results.

Related: Slovene-British Team Conquer North Face of Latok, the “Holy Grail” Of High Altitude Climbing

Two names that appear in the book are Marko Prezelj and Silvo Karo, and one of the great themes of the stories McDonald tells is the bond that exists among climbers, a breed apart in terms of abilities, motivations and goals. It was thus a delight to find the following video of Prezelj and Caro talking about a young Slovene climber, Luka Lindič, born in 1993. Not only do the older men look happy, healthy and at peace, but they’re still active in the scene and passing on their knowledge and experience to the next generation, alpinists like Lindič who know they’re standing on the shoulders of giants.

So enjoy the video, and – if you’re not aware of Slovenia’s outstanding record in the Himalayas, Patagonia and elsewhere – bear in mind that this is yet another field of human endeavour in which the country is truly first class, and one that it’s well worth paying attention to.