If your experience of Slovenia is anything like mine you’ll have friends and family who live in the country, know the land well, and are accomplished foragers, bringing home mushrooms, herbs, flowers, berries greens and other edibles from walks in the forest along routes that are jealously guarded, and followed when the season and weather is right.

Of course, such activities require certain knowledge, not least of which is what’ll kill you in the kitchen. Which is a roundabout way of introducing the work of Karsten Fatur, a PhD student at Ljubljana University who recently published a paper with the intriguing title “Sagas of the Solanaceae: Speculative ethnobotanical perspectives on the Norse berserkers”. Having read it, and learned more about the author, including his projects on Ritual plant usage among pagan groups in Slovenia, "Hexing herbs" - use of anticholinergic Solanaceae in Slovenia, and Hallucinogenic plant use in Slovenia, I got in touch with some questions, and he was kind enough to reply.

Wikipedia: Medieval illustration of a mandrake root

What did you focus on in your master’s degree, and what was the experience of studying in the UK (at the University of Kent) like?

My master’s degree was in ethnobotany, with my dissertation focusing on ritual plant usage among Staroverci [“People of the old religion”, i.e., pagans] here in Slovenia. I already had an interest in hallucinogenic plants, and surprisingly few were mentioned in religious rituals here during my research. As such, I ended up deciding to focus on this more as part of my doctoral work as I knew people here surely were making use of such plants and mushrooms.

As for the experience in England, it was very wet! The stereotype of it always being rainy in England is unfortunately true. So it wasn't very nice to live there and never see the sun, but the rain does make the vegetation seem very lush, and walking in the woods there it somehow seems more vibrant and alive than here. The vegetation is also a bit different than here, so it was interesting to experience living around and studying those plants.

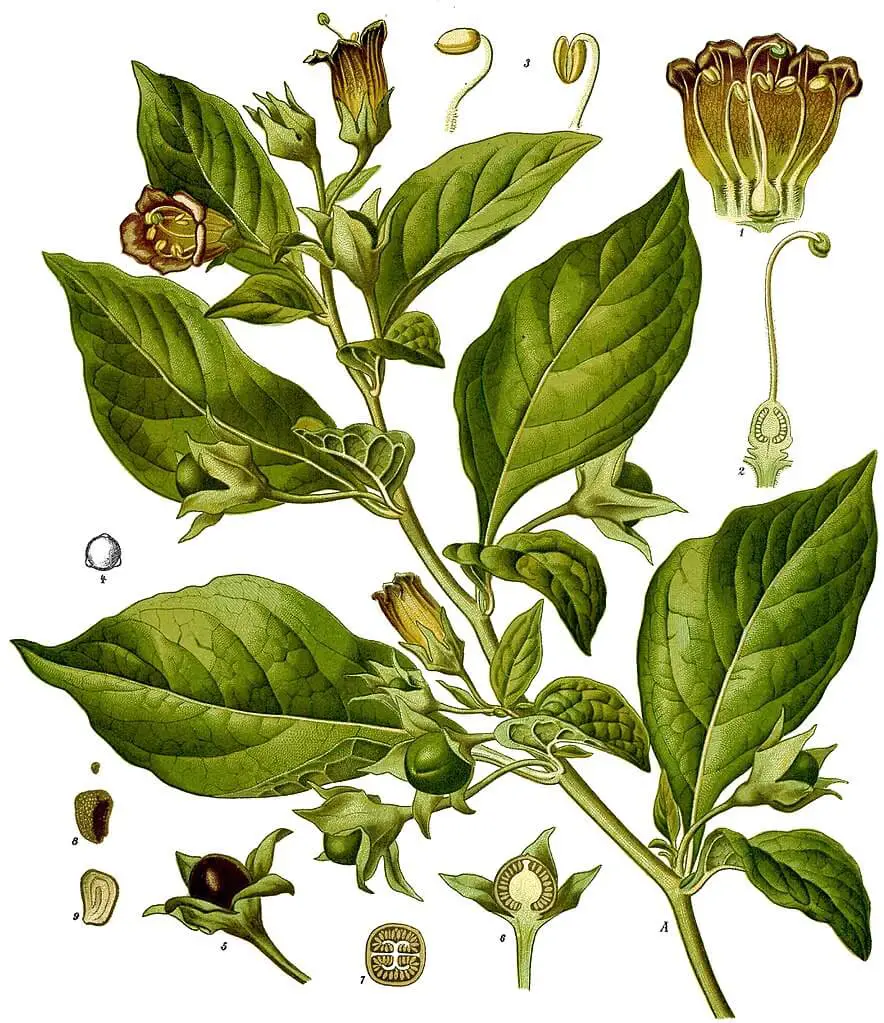

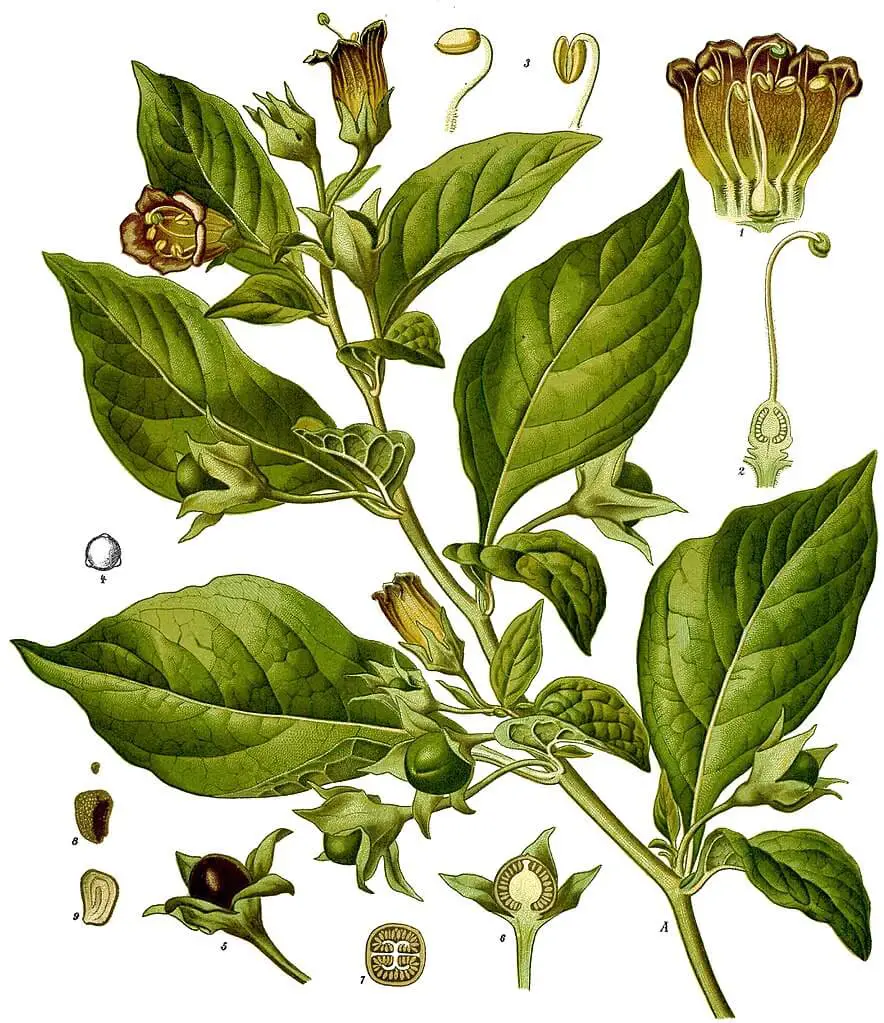

Wikimedia: Atropa belladonna

How would you describe the field of ethnobotany, and how did you get interested in it?

Ethnobotany is difficult to define as it is inherently situated between academic fields. Honestly, there are probably more definitions than there are ethnobotanists! I tend to describe it informally as a crossing between anthropology and botany that focuses on how people use plants, though many people I know and have studied with would accuse me of oversimplifying in saying that. Still, for my purposes, it works.

As for how I got interested in it, I had a book suggested to me when I was an undergraduate student (One River, by the ethnobotanist Wade Davis, a student of Robert Schultes) and after reading it completely fell in love with the field. Before this I had worked and volunteered in greenhouses and taken botany courses as electives, but wasn't sure how to combine my love of plants with my desire to do ethnographic fieldwork, but this showed me the way to do it.

Wikimedia: Datura metel

Your current research is on Solanaceae plants in Slovenia. Can you give a brief introduction to these plants?

Solanaceae is a family of plants that includes potato, tomato, bell pepper, eggplant, and many others that are familiar to most people. That being said, it also includes some very poisonous plants that have hallucinogenic effects, and these are the plants I focus on. In Slovenia, this means Atropa belladonna, Datura and Brugmansia spp., Hyoscyamus niger, Scopolia carniolica, and Mandragora spp.

Again, all of these plants are incredibly poisonous and should not even be touched let alone used. I certainly do not advise using any of them, though some people do and have for millennia. They have been used for many things, but a quick list includes medicine (the only difference between a medicine and a poison is dose!), as recreational drugs (again, usually ending with people in the hospital, so not advisable), and as poisons by assassins. I actually have an article coming out within the next few months that reviews the uses in Europe much more specifically, so that is something to look out for, for those who are interested.

Most use has stopped since the plants are so dangerous, and now they are used much less. My research is actually focusing on just how much and how they are still being used. The effects of these plants are incredibly varied, but usually include confusion, hallucinations, flushing of the skin, irritability, as well as having effects on the smooth muscles of our bodies that can affect our respiratory and cardiovascular systems, potentially leading to death. These plants are incredibly dangerous, since the amount of active substance that they produce varies immensely, so even collecting plant material from the same organism can lead to very different doses; this makes overdosing more of a rule than an exception since there is no way to know how much of the toxic ingredients you are ingesting.

Wikimedia: Brugmansia sp, Paul K from Sydney cc-by-2.0

What are some of the surprising things you’ve learned about these plants?

One of my favourite weird discoveries about these plants is a theory that I published a few months ago in a paper that can be found here, or a summary article published on the popular science blog, IFLscience, that can be found here.

In brief, after a lot of reading for other purposes, I found that the famous Viking Berserkers were probably using one of these plants to create their wild warrior frenzy! A lot of theories have been presented for what may have been the cause of the states of rage they entered in battle, but they all are lacking in some ways. The most popular one involves a hallucinogenic mushroom, Amanita muscaria, but the symptoms that this mushroom cause are not as similar to what records show for the berserkers as those that would be seen from one of these Solanaceae plants.

Wikimedia: Mandragora spp., tato grasso CC-by-SA-2.5

In terms of Slovenian ethnobotany, what other plants are of interest?

This is a good question, which unfortunately needs to be answered with "I don't know... yet!"

There has been some ethnobotanical research done in Slovenia, but not very much. My current research is seeking to address this through two main projects: uses of hallucinogenic plants, and uses of medicinal plants. Within both I am also seeking information specifically on the uses of these Solanaceae plants, but also more general information about other plants.

That being said, plants are used for many other things! Wood is used for carving and building, flowers are used in many rituals related to death and burial (for example), and many food crops are used. All of these aspects of ethnobotany would be interesting areas of study in Slovenia! Unfortunately, I can only do so many things at once!

Wikimedia: Hyoscyamus niger, h. zell gnu free license

What are the most exciting developments in the wider world of ethnobotany?

This depends on what most interests someone. For some people, discovery of a new weaving technique for baskets made from reeds may be the most exciting thing. In general, though, a lot of ethnobotany is linked to drug discovery.

Many medicines that we use today are actually from (or at least were first discovered in) plants. So many of the great discoveries of ethnobotany involve seeing medicinal plants being used and then isolating the active ingredients to see what substances may be responsible for their medicinal effects. This is where the line between ethnobotany and pharmacy begins to blur. So even though we cannot directly study ethnobotany in Slovenia, there is a great biological pharmacy department that teaches the pharmaceutical side of things. As a doctoral student though, things get more flexible. I am technically a student at the biotechnical faculty studying biology, but my mentor is a professor at the faculty of pharmacy in this department. People can also specialize in ethnobotany by studying anthropology (that's exactly what my bachelor’s degree was in), but a background in botany is also very important in this case.

Wikimedia: Scopolia carniolica, flobbadob, CC-by-0

Where can people follow your work?

The best way to do that is probably my Research Gate profile, where I put up articles that I have published. There are only a couple there now, but I have quite a few going through the publication process now, so hopefully soon there will be lots of interest there.

Related - Herbal Medicine in Slovenia: A Flower For Each Disease