The courtyard has a model of the Castle with braille, so blind people can also get a feel for where they are. There’s also a Eurokey bathroom not far from the Viewing Tower. Photo: JL Flanner

A visualisation of the Roman fort, as seen in the Virtual Castle exhibition. Photo: Ljubljanski grad

1. It’s not all the same age

The hill was the site of a wooden Roman fort, but work on a castle didn’t start until the 11th century. While you can still see some of the Spanheim Castle, dating back to the 12th century, near the old grape vine in the courtyard, the oldest large structure is the brownish Pentagonal Tower – which was built in the 15th. This is when the original Castle was remodelled and expanded, with more structures added over the following 200 years. However, as the city prospered its rulers preferred to live down the hill, and the Castle eventually fell into disuse and disrepair, a state that was exacerbated by an earthquake in 1895. Much of what can be seen today was completely rebuilt since 1969, based on the remains of the 12th century structure. A good exhibition showing this work, with many pictures, can be found in the Lapidary, one of the halls under the Castle.

Before and after the renovations and rebuilding. Photos: Ljubljanski grad

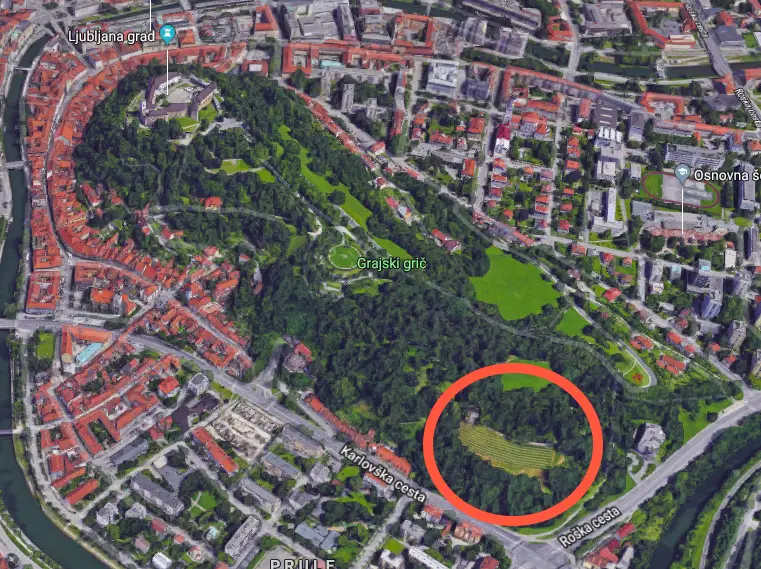

The Castle vineyard is at the other end of the hill. Photo: Google Maps

2. It has a “daughter” of the oldest vine in the world

The castle now has its own vineyard, planted in 2016 and producing its first wine in 2018. While you’ll have to walk to other side of the hill to see these vines there’s one right inside the Castle walls, and a very special one indeed. It’s the “daughter” of the oldest vine in the world that still produces grapes, grown from a cutting that was given to the City of Ljubljana by the City of Maribor in 1990, where the record-breaking vine, now more than 400 years old, can be found.

Photo: JL Flanner

3. There are triangles, circles and squares in the walls

Walk around the Castle and you’ll see some strange looking slits that aren’t windows, one set with triangular openings at the bottom, another with circular ones. These are defensive features, with the former being used by archers – who could shoot up to 200 meters – and the latter being openings for cannons. The many small square holes you’ll see in the walls are not in fact openings, but simply part of the structure that was used to support scaffolding in times of repair and renovation.

Where the moat used to be. Photo: Ljubljanski grad

4. The moat is no more

The Castle once had a moat, but only on one side, as the other was defended by the steep slope of the hill. Its here were note that Slovenia has dozens of castles, and very few of them were not successfully besieged at one time or other in their history, with Ljubljana’s being one that resisted all such attacks due to its location, design and, one imagines, some luck.

The building that now houses the old well. Photo: Ljubljanski grad

5. An ancient well was buried and lost

The oldest known feature on the hill is the well that’s just outside the Castle walls, inside a small building with a moss-covered roof. This was dug in Roman times, although the crown and structure it sits within were only built in the 19th century. The well itself was lost to history for several centuries, having been filled in and buried under a mound of earth when the moat was being dug, in order to prevent a besieging army from using the water or poisoning the well. In a curious twist of fate the well was only rediscovered in the 19th century, when prisoners who were locked up the Castle were tasked with filling in the moat, taking soil from the artificial hill nearby, and thus uncovering the ancient structure.

A tread wheel for getting water from the well. Photo: JL Flanner

6. A hamster wheel to draw water

Visit the well and you’ll see a wooden tread wheel to one side, one of only two surviving examples of such a device, the other being in France. Into this was placed two blindfolded prisoners, who then walked like hamsters in a wheel in order to bring a 40-litre bucket of water to the surface. The prisoners then turned around and walked the other way to lower the bucket again. Why were they blindfolded? So they didn’t get dizzy.

Fleischemann’s parsnip. Photo: Ljubljanski grad

7. It has its own native vegetable

Fleischemann’s parsnip (Pastenica sativa var. fleischmanni) is a plant that was first identified on Castle Hill in the 19th century, with this area remaining it’s only confirmed natural habitat. While the vegetable is now also grown at the University of Ljubljana’s Botanic Gardens, you can still see it at the Castle, just inside the courtyard, on the right, and near the old vine mentioned above. Visitors with a special interest in botany are directed to Fleischemann’s Path, which leads from the Botanic Gardens to the Castle, and for which a very informative booklet is available at the latter’s Info Centre (as well as in PDF form, here).

Fleischemann’s Path is one way to enjoy Castle Hill. Photo: Ljubljanski grad

The Pentagonal Tower, seen from outside, which once was connected to a drawbridge going over the moat. Photo: JL Flanner

8. Small doors slow big soldiers

The original main entrance to the Castle, the one reached by a drawbridge over the moat, is in the Pentagonal Tower, one of the oldest surviving parts of the complex (and made of mostly brown stone, rather than white, like the later elements). You can see two openings in the middle of the tower in the photo above – a bigger one for horses and carts, and a smaller one for people. And while it’s true that the average height of a Slovene has increased significantly over the centuries, this opening was small even for the time it was built. This was no accident, but instead another defensive measure, making it more difficult for people to rush in uninvited, something also aided by a now-demolished wall that stood between in the tower this entrance and the courtyard.

Can you see the Roman stones? Photo: JL Flanner

9. There are Roman remains in the walls

The builders of the Castle made use of old stones that were already in the city, having been cut and worked by Romans more than a millennia before. Look carefully and you’ll sometimes see a slab of rock with a design or even writing carved into it, and here you can pause and imagine the life it once had in the ancient city of Emona. In the early 20th century, before Mayor Hribar bought the Castle for the city, there was talk of moving some of the stones down the hill for use in new structures.

Photo: JL Flanner

10. A dragon lived under a Castle

The legend of the Ljubljana dragon goes back into the mists of time, but Roman accounts suggest it arose from fires and explosions that occurred in the Ljubljana marshes due to the release of methane. Whatever the origin, the story developed into one in which a daring knight called George came to visit the city in order to slay the dragon that lived under the Castle, and thus protect local virgins from the creature’s annual hunger.

Coats of arms on the ceiling of the chapel. Photo: JL Flanner

11. The chapel is full of nobles

St George’s Chapel, named after the dragon-killing knight, isn’t decorated in usual church style, and if you look up to the ceiling you’ll see 60 or so coats of arms from various noble families instead of, say, the more common cherubs, saints and angels. If you’d like to attend a mass here you can, although only on St George’s Day and the Midnight Mass at Christmas. You can also get married in the chapel, with an office in the courtyard set up to arrange this (as well as an online site).

A memorable venue for a memorable day. Photo: Ljubljanski grad

A dragon on the wall by the entrance. Photo: JL Flanner

Another dragon hiding on some of the doors. Photo: JL Flanner

12. There are still hundreds of dragons in the Castle – STAIRS / DOORS

The dragon motif can be seen in various places around the modern Castle. Some of these are very subtle, as on certain doors, while others could dull the mind with repetition, such as the dragon that’s seen on each step up to the Viewing Tower.

And there are hundreds of dragons on the steps to the top of the Viewing Tower, which, as the following pictures show, is worth going up. Photo: JL Flanner

Photo: JL Flanner

Photo: JL Flanner

Photo: JL Flanner

13. It has the best view in town

The Viewing Tower is the highest point in Ljubljana, and thus provides fantastic views of the city and all the way to the Alps. While it looks old it was only built in 1848, nine years after the invention of photography in the form of daguerreotypes.

Some of the 19th century prison cells. Photo: Ljubljanski grad

14. Not everyone wanted to stay there

In medieval times there were two prisons in the castle. An open-air one, still seen the courtyard, for peasants and Turks, and a covered one, offering greater comfort, for the nobility. The castle became a prison again in the 19th century, from 1815 until 1895, when a strong earthquake damaged much of the city, although it didn’t have this function for 20 years during this period, from 1848 to 1868. The Castle was used as a prison again during both world wars, and one notable occupant of a cell was the writer Ivan Cankar, jailed for a short time in 1914 for being “pro-Serbian”. Those wanting to learn more about this part of history are in luck, as the Castle has regular tours examining its use as a prison, as well as a permanent exhibition.

This marks the "well" that Erasmus escaped down. Photo: JL Flanner

15. A tale of two toilets

Walk out of the Pentagonal Tower and look at the ground, where you’ll see a “flower”. This was once a well, or at least pretended to be, but was in fact an escape route, although since it took anyone fleeing the Castle out through the worst part of a medieval toilet – the pit full of human filth – it was only used under the most pressing circumstances. One man that escaped from the Castle in this manner was Erasmus (aka Erazem of Predjama), the noble from Predjama Castle who was imprisoned for killing an army commander. After he fled Ljubljana, got out of his clothes and took a good bath, he hid in his own castle for more than a year while the authorities tried to starve him out. This task was made impossible by the numerous secret passages to the outside that enabled Erasmus and his staff to stay well-fed and watered. Then, in another of those curious twists of history that so delight writers of articles like these, having escaped via one toilet Erasmus was killed by a cannonball while using another, his own.

The City of Ljubljana's coat of arms features a dragon and the Castle. Photo: Wikimedia

16. It's now owned by the City of Ljubljana

When Mayor Hribar bought the Castle for the city the cost was just half the amount needed to build Dragon Bridge, a sign of the disrepair, disuse and lack of respect for this once central structure. Mayor Hribar wanted the Castle to become a cultural and tourist centre, and also planned to build an elevator to the top. He would thus, one assumes, be delighted to see how the place has developed over the last few decades.

Getting water when the Castle was in ruins. Photo: Ljubljanski grad

The same well today: Photo: JL Flanner

17. It once housed the poor

After the city took over the Castle, but before it was renovated and rebuilt, the ruins served as a home for many families. These weren’t nobility, however, but drawn from the poor, and the living conditions at the time weren’t the best, with many families having to share one bathroom.

18. There are several ways of getting to the top

The funicular was built in 2006, but the idea for an elevator from the city to the Castle was first proposed by Mayor Ivan Hribar. The castle can also be reached by road or on foot, with several attractive paths going up from the Old Town and an electric “train” that visits on its tour around town (details here).

The starts of two paths to the Castle, one at either end of the Old Town, with the one at the top being just around the corner from the funicular

The electric train that can take you to Castle and other sights in town. Photo: JL Flanner

A trail in autumn. Photo: JL Flanner

19. It’s a great place to get some exercise and air

The Castle is on one end of the hill, while the other has a small forest and many trails (see here) that provide a way to escape the city while never being more than 10 minutes from the centre. As such it attracts dog walkers, hikers and joggers, and there’s even a small exercise area with some equipment if you want more of a workout.

Come here for a workout with some wood. Photo: JL Flanner

Šance after Plečnik had done his work, with some good views of the area. Photo: Ljubljanski grad

20. Plečnik was here

It’s while walking from the Castle to these trails on the other end of the hill that visitors may come across Šance, the site of medieval ruins that were redeveloped by Jože Plečnik into stairways, viewing platforms and arcades, from which some interesting view of the city can be obtained before going on to the forest.

Plečnik in your pocket. Photo: Wikimedia

21. But he wanted to do more

Since Plečnik is the architect most associated with Ljubljana in its current form, it’s perhaps no surprise he had greater plans for the castle than simply redesigning the less glamorous end of the hill. One of these was for “the Slovene Acropolis”. Plečnik proposed this wildly ambitious scheme in the 1940s, which would have seen the Castle partly demolished and partly absorbed by a huge octagonal complex that was intended to serve as the a National Parliament building. His next plan for the Parliament was the “the Cathedral of Light”. This also remained unbuilt, but can be found across Europe on one side of the Slovenian 10 cent coin.

Strelec, in Archer's Tower. Photo: Ljubljanski grad

22. You can still eat like a lord

As befits the Castle’s status as the main attraction in the city, it also houses one of Ljubljana’s best restaurants, Strelec, meaning “archer”, so named because of its location in Archer’s Tower, on the right side of the entrance to the complex. This offers a fine-dining approach to Slovenian food, at fine-dining prices, with a PDF of the menu here. There’s also a Castle café offering more casual fare.

Some of the art on the wall of Strelec. Photo: Ljubljanski grad

23. Fine art with fine dining

If you’re lucky enough to eat at Strelec then be sure to look at the walls as well as the menu. Here you’ll see some sgraffito paintings by the architect, painter and university professor Boris Kobe (1905–1981) and the painter Marij Pregelj (1913–1967). These were made in the early 1950s, and, in an almost comic-book style, tell nine traditional Slovenian folk tales.

There ae Time Machine Tours that tell the story of the Castle with the support of local actors. Photo: Ljubljanski grad

24. The best way to see it is with a tour

While you can learn quite a lot by reading about the Castle, online or in the guides available at the Info Centre, the best way to see the Castle, and have all your questions asked, is by going on one of the many tours on offer. These provide at least an hour’s entertainment, and the price of the ticket will also get you into the Viewing Tower. If a tour is unavailable on your visit, then you can pick up an audio guide at the Info Centre, available in 14 languages

The Info Centre has everything you need. Photo: JL Flanner

Dancing in the courtyard. Photo: JL Flanner

25. It’s a busy place

The Castle isn’t just a tourist attraction, but a place that still commands attention as a cultural centre and part of the living heritage of the city, and so the country. The numerous rooms and spaces it offers see more than 500 events each year, from concerts to conferences, weddings to exhibitions, diplomatic receptions to stand-up comedy shows, and not a week goes by without something to enjoy within its walls, all of which you can learn about on the Castle’s website.

Movies under the stars. Photo: Kinodvor

The Castle is open all year, although with some changes with the seasons. January, February, March and November its open 10:00 to 20:00. April, May and October from 09:00 to 21:00. June, July, August and September from 09:00 to 23:00. December 10:00 to 22:00. However, now that these times are for the main Castle complex, and not necessarily for all the attractions, with more details here.

Related: 25 Things to Know about Slovenia's Green City of Dragons

Entrance to Castle courtyard is free, but if you want to see more you'll need to buy a ticket at the entrance, funicular station or Info Centre, with a basic ticket currently 7.50 euros for adults and 5.50 for children, students and pensioners, and there's also a family ticket for 19 euros. Note that tickets to tours also include entrance to all parts of the Castle, with more details here.