Business

STA, 16 January 2019 - Migration flows are becoming increasingly important for the Slovenian economy, the central bank says in its monthly bulletin. Banka Slovenije notes a workforce shortage for occupations requiring intermediate qualifications, meaning that employers have started to hire foreign citizens.

"With Slovenians moving away, the hiring of foreigners has preserved a positive net migration since 2015."

Related: Foreigners now hold 10% of the jobs in Slovenia

"However, on average the structure of the foreign worker population in terms of education and vocation is poorer than that of domestic workers."

Unless Slovenia starts producing higher value added and introduces direct measures to prevent brain drain, the country's productivity growth could become too low to keep up with the most developed countries, and the effects of an ageing population all the more pronounced, Banka Slovenije said.

Brain drain is lost potential for the state that has invested into the education of highly-trained work force now leaving the country, it added.

Related: 1 in 8 residents of Slovenia is now a resident

The central bank believes brain drain happens for a number of reasons, among them a relatively low value added of a large part of the economy.

Also touching on exports, the bulletin says that the international environment is becoming less advantageous for Slovenia's exporters, as growth in the EU as well as globally has been slowing down.

Although the estimate of economic growth for Slovenia's trade partners is somewhat lower than in 2018, the outlook still indicates "solid conditions" for the exporting companies.

STA, 12 January 2019 - The economic and financial crisis in Slovenia, which started in 2009, brought a significant growth of unemployment, with the number of the unemployed more than doubling to almost 130,000 at the beginning of 2014. The situation on the labour market has been improving lately, with shortage of certain staff actually becoming a problem.

The number of registered unemployed persons was up steeply in 2009 and peaked at the beginning of 2014 at almost 130,000, which was around double of that before the crisis.

It was in 2014 when the number finally started to decline, with the improvement on the labour market accelerating in 2016 and 2017 and continuing in 2018, with the number standing at 78,534 at the end of the year.

Projections for the coming years speak about an additional improvement, with the number of registered unemployed expected to drop to the pre-crisis level by 2021 barring major negative shocks.

Staff shortages are now a growing issue, along with unemployment among those aged 55+

There is a large number of structurally and long-term unemployed people in Slovenia and hard-to-employ people, whose activation requires additional active employment policy measures.

Given the circumstances, a large number of companies have already started reporting shortages of adequately trained staff, which is becoming a limiting factor in the implementation of their strategies.

The number of the active working population is also growing again, and the employment rate exceeded the pre-crisis level in 2017. The total number continued to increase in 2018 to reach 1.022 million in the third quarter, a 23-year record.

Although the total employment rate is somewhat higher than the EU average, Slovenia fares much worse when it comes to the employment rate in the 55-64 age category despite an improvement in recent years.

In 2017, it stood at 43% or 14 percentage points below the EU average. Slovenia is meanwhile recording better progress in the under-25 category, but its rate is still at roughly half of the EU average.

Employment Registered Survey

rate (%) unemployment (%) unemployment (%)

2008 73.0 6.7 4.4

2009 71.9 9.1 5.9

2010 70.3 10.7 7.2

2011 68.4 11.8 8.2

2012 68.3 12.0 8.9

2013 67.2 13.1 10.1

2014 67.7 13.1 9.7

2015 69.1 12.3 9.0

2016 70.1 11.2 8.0

2017 73.4 9.5 6.6

* The figures are annual averages

Source: Statistics Office, Employment Service

Pay in Slovenia after the crisis

Growth of wages slowed down in the crisis years and came to a stop in 2012 and 2013. Wages started to grow again noticeably only in 2017 and 2018, when the growth of gross wages exceeded 3%, with the trend expected to continue and grow even stronger in the coming years. Domestic and foreign macroeconomic analysts are stressing that the growth of wages will not significantly exceed the growth of productivity and undermine the competitiveness of the economy.

Data for the period as of 2008 also show that the growth of wages was higher in the private than in the public sector. While in the public sector the crisis was fought with lay-offs, there were no dismissals in the public sector, with the number of employees even increasing in certain activities. Civil servants did contribute their share by accepting austerity measures, which are only now being gradually abolished.

Related: Economic crisis that produced a "lost decade" in Slovenia

In the years after 2013, contributing significantly to the real purchasing power was a low inflation, which was noticeable again only in 2017 and last year, when it reached 1.4% according to preliminary estimates.

What also marked the crisis years was a raise of the minimum wage of more than 20% in 2010, which enraged the employers, who blamed the rise in the unemployment rate in the coming years on this measure. Trade unions were meanwhile noting that the minimum wage was still below the minimum costs of living and that all bonuses were calculated into it.

In the recent years, the minimum wage has been increasing more gradually, standing at EUR 843 gross last year. This year it will increase to EUR 886 and in 2020 to EUR 940 gross under the latest legislative changes, which also regulate the elimination of bonuses from the minimum wage as of 1 January 2020.

Inflation (%) Average net wage* Average gross wage*

in EUR growth in % in EUR growth in %

2008 2.1 899.8 7.8 1,391.4 8.2

2009 1.8 930.0 3.3 1,439.0 3.4

2010 1.9 966.6 3.9 1,494.9 3.9

2011 2.0 987.4 2.1 1,524.6 2.0

2012 2.7 991.4 0.4 1,525.5 0.0

2013 0.7 997.0 0.6 1,523.2 0.0

2014 0.2 1,005.4 0.8 1,540.2 1.1

2015 -0.5 1,013.2 0.8 1,555.9 1.0

2016 0.5 1,030.2 1.7 1,584.7 1.8

2017 1.7 1,062.0 3.1 1,627.0 2.7

* Annual average

Source: Statistics Office

Added value and productivity

In addition to the demographic trends, one of the key challenges for long-term development and economic competitiveness of Slovenia are growth in productivity and added value in the economy, to which growth of wages and well-being are tied. In this segment, the economic crisis brought stagnation and even a slight decline, while in comparison with the EU average, productivity in the Slovenian economy in 2018 was still lower than in the pre-crisis 2008.

Gross added value per employee was up in the 2008-2017 period, but is still well below the EU and eurozone averages, at 63% of the EU average and 57% of the eurozone average.

Related: Banks were at the center of the financial crisis in Slovenia

Increasing productivity and added value is a challenge both for the economy and economic policy. Businesses have set an ambitious goal of reaching EUR 60,000 in added value per employee, EUR 50bn in exports and an EUR 2,300 average wage by 2025, which is why they except measures from the state ranging from the tax police to the immigration policy.

Among the necessary measures both in the economy and institutions, they have pointed to measures for growth of investments in new production capacities and new technologies and digitalisation, a growth in investments in research and development, which as a share of GDP dropped from 2.6% in 2013 to 1.93% in 2017.

Labour productivity, % of EU average

Per employee Per hour worked

2008 83.5 83.8

2009 79.9 79.0

2010 79.4 78.2

2011 80.6 80.3

2012 80.0 79.8

2013 80.3 78.9

2014 81.2 78.9

2015 80.5 77.9

2016 80.5 79.7

2017 81.0 81.5

Source: Statistics Office

Gross value added, in EUR

Per employee EU average Eurozone average

2008 34,759 55,079 61,492

2009 33,694 52,917 60,581

2010 34,107 55,506 62,638

2011 35,594 56,951 64,164

2012 34,854 58,247 64,834

2013 35,643 58,850 65,863

2014 36,893 60,247 66,991

2015 37,758 62,818 68,678

2016 39,091 62,418 69,398

2017 40,136 63,276 70,861

Source: Eurostat

All out stories on the Slovenian economy can be found here

Ascent Resources, the UK-based firm engaged in a long-running attempt to begin fracking at Petišovci, a plan that has been delayed due to a lack of permits, said on Monday that it’s now looking to develop other projects outside Slovenia.

A report published on the London South East website, sets out how the company is still waiting on permits to re-stimulate it’s existing wells to produce more gas from the field, and install a processing facility to enable the natural gas it produces to enter the Slovenian national grid.

The story became more heated in late 2018, with accusations that Ascent Resources shareholders, or other interested parties, had been sending threatening messages to the Slovenian Environment Agency, as reported here, as well as threats by the company to sue the Slovene government for damages.

The firm’s Chief Executive, Colin Hutchinson, is quoted as saying "While the Petišovci project remains a potentially very valuable asset, I am pleased that we now have a way forward that is not entirely based on Slovenia and the award of permits.”

At the time of writing the shares of Ascent Resources (AST) were trading at 0.32 pence in London, down from 1.40 pence a year ago.

STA, 12 January 2019 - The global financial crisis, which erupted in 2008 with the collapse of Lehman Brothers, hit Slovenia with a delay, but it exposed huge weaknesses that had built up in the majority state-owned banking system. By 2012 Slovenia was locked out of financial market, and it took until the bank bailout in late 2013 before the sector recovered.

In the run-up to the crisis, credit growth was buoyant, driven by cheap money after interest rates collapsed following the changeover to the euro in 2007.

Loans to the non-banking sector surged by almost two-thirds between 2006 and 2008. Banks financed the expansion mostly by securing financing from foreign banks.

The crisis thoroughly razed the banking landscape.

Banks' total assets peaked at over EUR 50bn in 2010 before reaching a low of just 37bn six years later.

Related: Economic Crisis that Produced a “Lost Decade” in Slovenia

Similarly, lending contracted by more than a third between 2010 and 2016, as banks deleveraged to pay back their foreign loans rather than extend new loans to Slovenian businesses.

On the other hand, deposits remained robust as households responded to the crisis by tightening spending, which deepened the economic crisis but gave banks a lifeline when foreign financing dried up.

The total volume of loans slipped slightly during the crisis as households drew down their savings, going from EUR 23.9 bn in 2010 to EUR 22.4bn in 2013, but the contraction was never as severe as the tightening of lending.

Bank statistics

Total assets Loans to non-banking sector

(in EUR m) (in EUR m)

2006 34.1 20.6

2007 42.6 28.5

2008 47.9 33.7

2010 50.8 34.7

2013 40.3 24.3

2014 38.7 21.5

2016 37.1 20.5

2018* 38.3 22.2

* As of 31 October

Source: Slovenian central bank

A property bubble that burst in 2010

The credit explosion leading up to the crisis inflated a property bubble, which burst post-2010 as large construction companies that also financed their own projects collapsed one after the other, as did over-leveraged financial holdings.

The share of non-performing loans started to soar, forcing banks to set aside increasing provisions and writing down assets, leading to a negative spiral.

Whereas foreign-owned banks received capital injections from their shareholders, the three biggest banks in the country were all in state ownership, requiring growing amounts of public funds to keep them afloat.

Video: Slovenia's Economic Crisis, 2012

The story came to a head in December 2013, when the treasury spent EUR 3.5bn recapitalising NLB, NKBM and Abanka, wiping out shareholders and junior bondholders in the process. Two smaller banks, Probanka and Factor Banka, were wound down.

At the same time, about four billion euros in non-performing loans were transferred onto the newly-established Bank Assets Management Company (BAMC), which also absorbed the assets of Probanka and Factor Banka.

After the banking system was bailed out banks were flush with cash and largely freed of non-performing loans, but it took several years before lending recovered.

Bank performance

Net profit Net provisions, write-downs

(in EUR m) (in EUR m)

2008 208 -120

2009 162 -279

2010 -99 -811

2013 -3439 -3809

2014 -106 -650

2016 364 -96

2017 443 43

2018* 452 45

* As of 31 October

Source: Slovenian central bank

Lawsuits related to the period

Echoes of this period continue to reverberate five years later, as lawsuits by subordinated bondholders and shareholders wiped out in the bailout make their way through courts.

These investors have targeted in particular the valuations that determined the size of the bailout, alleging that Slovenia had been the target of speculators and a guinea pig for new EU bank resolution rules.

The commotion over the bailout resulted in criminal investigations at the central bank, the resignation of governor Boštjan Jazbec and, recently, criminal charges against the board of governors serving at the time of the bailout.

The costs of the bailout accounted for a significant chunk of the increase in general government debt during the crisis, which ballooned from 22% of GDP in 2008 to almost 84% of GDP by 2015.

The surging debt was accompanied by growing debt servicing costs, as the precarious state of the economy during the crisis led to higher borrowing costs; for a while, Slovenia was practically locked out of the eurobond market and had to borrow in US dollars.

Public debt did not start to decline until 2016, when the economic recovery was already in full swing. In the past two years the treasury has been busy replacing dollar debt with euro bonds and debt has started to decline at a more rapid pace towards the eurozone ceiling of 60% of GDP.

General government finances

Deficit Debt Debt servicing costs

(% of GDP) (% of GDP) (EUR m)

2008 -1.4 21.8 326.1

2009 -5.8 34.6 326.4

2010 -5.6 38.4 476.7

2011 -6.7 46.6 510.6

2012 -4.0 53.8 632.5

2013 -14.7 70.4 827.0

2014 -5.5 80.4 1082.6

2015 -2.8 82.6 1028.8

2016 -1.9 78.7 1064.0

2017 +0.1 74.1 977.3

Source: Eurostat, Statistics Office, Ministry of Finance

STA, 12 January 2019 - Ten years ago Slovenia faced the onset of a major financial and economic turmoil and it was not until 2017 that the country's GDP returned to pre-crisis levels. However, even as some described the period as a lost decade, the economy has emerged from it healthier and more resilient to a potential new crisis.

Related Video: Slovenia's economic problems, 2012

After a few years of rapid expansion peaking at 6.9% in 2007, Slovenia's economy contracted by 7.8% in 2009 in the wake of the outbreak of a global financial crisis in what was one of the biggest slumps in the EU, after those in the Baltic countries and Finland.

After minor upwards corrections in 2010 and 2011, faltering domestic private and state spending and fast-falling investment led to two more years of economic decline, which was exacerbated by a deterioration in the banking sector and the financial market's growing distrust of the country.

The crisis bottomed in the third quarter of 2013 and Slovenia's GDP has been increasing ever since, accelerating up to the annual rate of almost 5%. The growth is estimated to have proceeded at roughly the same pace in 2018, after which it is expected to slow down to about 3% in the coming years.

Despite the accelerated growth seen in the past few years, real GDP did not return to pre-crisis levels until 2017, which means that the country needed almost a decade to come back to the point it departed from at the end of 2008.

A major domestic factor deepening the crisis was a slump in investment, both corporate investment and housing construction and major investments in road and rail infrastructure after a strong growth in the pre-crisis years.

Between 2008 and 2013, the value of construction work was more than halved, before increasing in 2014 driven by completion of EU-subsidised projects, only to fall yet again. It was not until 2017 and 2018 that the sector saw more sustainable double-digit growth rates.

The collapse in the construction industry caused many construction companies to go bust, including giants such as SCT and Primorje. It also paved the way for new and so far minor players to make a breakthrough in the field.

Real GDP growth (%) Real GDP per capita (EUR) 2008 3.3 19,200 2009 -7.8 17,500 2010 1.2 17,700 2011 0.6 17,800 2012 -2.7 17,300 2013 -1.1 17,000 2014 3.0 17,500 2015 2.3 17,900 2016 3.1 18,500 2017 4.9 19,400 * Reference year is 2010

Final household Gross capital General government

consumption formation final consumption

2008 2.6 7.0 4.9

2009 0.9 -22.0 2.4

2010 1.1 -13.3 -0.5

2011 0.0 -4.9 -0.7

2012 -2.4 -8.8 -2.2

2013 -4.2 3.2 -2.1

2014 1.9 1.0 -1.2

2015 2.3 -1.6 2.4

2016 4.0 -3.7 2.7

2017 1.9 10.7 0.5

Value of construction work (%) No. of construction jobs 2006 15.6 72,810 2007 18.5 82,140 2008 15.5 92,140 2009 -21.0 91,280 2010 -17.0 82,970 2011 -24.8 73,230 2012 -16.8 67,700 2013 - 2.6 62,960 2014 19.5 62,290 2015 - 8.2 62,550 2016 -17.7 61,930 2017 17.7 63,550

Source: Slovenia's Statistics Office, Eurostat

An even better indicator of the so-called lost decade is trends in GDP per capita and final individual consumption in purchasing power standards (PPS) as a percentage of EU, as two comparative indicators of a standard of living.

At the end of 2017 Slovenia trailed the pre-crisis level by both measures compared to the EU average. During that time, it has been overtaken by the Czech Republic among the new EU members, while Slovenia and the Baltic countries are catching up.

GDP per capita in PPP

(% of EU average)

2008 89.5

2009 85.1

2010 83.3

2011 83.0

2012 82.0

2013 81.6

2014 82.1

2015 81.8

2016 82.2

2017 84.0

Final individual consumption in PPP

(% of EU average)

2008 80.2

2009 79.9

2010 80.5

2011 80.8

2012 80.4

2013 78.1

2014 77.2

2015 76.5

2016 77.3

2017 77.2

Source: Eurostat

The crisis years and the post-crisis period have also produced some positive developments. The Slovenian economy has undergone a restructuring and boosted its competitive edge, so that exports recovered fast from the major contraction in 2009, and after an interim period of moderate growth, returned to strong growth in 2017. Exports at the end of 2018 are estimated to have outpaced those of 2008 by 50%.

Since exports have been increasing at a much stronger rate than imports, Slovenia also started to post a a trade surplus which (services included) in 2017 amounted to almost 10% of GDP and accelerated to 12% of GDP in the third quarter of 2018.

It was a key factor to the improvement of Slovenia's balance of payments and total economy balance. The latest available data indicate that Slovenia's economy posted a surplus of 9.1% of GDP in transactions with abroad in the third quarter of 2018.

The surplus has put the national economy on much healthier foundations, meaning it is no longer living beyond its means, but rather generates savings.

If Slovenia was a net debtor in the pre-crisis years, the banks settling their foreign debts and corporate deleveraging have turned the financial and corporate sectors and households into net creditors to abroad, so that the only net debtor remains general government, having taken out a great amount of foreign debt during the crisis.

Exports of goods and services Annual change (%)

(EUR bn)

2008 20.0 2.1

2009 16.3 -18.8

2010 18.6 14.6

2011 21.0 12.7

2012 21.1 0.3

2013 21.5 2.3

2014 22.9 6.4

2015 23.9 4.4

2016 25.0 4.3

2017 28.3 13.2

Balance of goods trade (EUR m) Total economy balance/

Current account balance

(% of GDP)

2008 -299.6 -4.8/-5.3

2009 -100.7 -0.2/-0.6

2010 -146.1 0.0/-0.1

2011 -155.6 0.0/0.2

2012 -101.7 2.2/2.1

2013 -565.4 3.6/4.4

2014 355.5 6.0/5.8

2015 635.1 5.6/4.5

2016 859.1 4.6/5.5

2017 658.8 6.3/7.2

Source: Slovenia's Statistics Office, central bank

STA, 10 January 2019 - More than 90% of Austrian companies doing business in Slovenia believe the country will continue to be an investment-friendly environment this year, follows from an annual survey conducted by the representation of the Austrian economy in Slovenia, Advantage Austria Ljubljana. The skills gap remains an issue.

"Austrian companies and investors are aware that they have an incredibly interesting, dynamic, stable, competitive and reliable market with plenty of opportunities right next to them," Peter Hasslacher, the head of Advantage Austria Ljubljana, said at the presentation of the survey.

Companies doing business in Slovenia are satisfied with the accessibility of public tenders and their transparency, and with the quality, education and the motivation of the workforce in Slovenia.

However, they find it increasingly hard to find suitable workers. Among those, 73% would require more workers with secondary education and almost 27% more workers with higher education.

According to Hubert Culik, the head of coatings maker Helios, which had been owned by Austria's Ring International before being sold to Japanese Kansai Paint, there is a lack of practical training of young people in Slovenia.

"Many of our new employees require lengthy practical training despite just having finished their studies," he said.

Other measures that would further improve the business environment in Slovenia include reducing taxes and red tape, improving the flexibility of labour market, and stabilising the political situation, according to the respondents.

Delo recently published an article on Ljubljana’s real estate market with the headline “Housing in Ljubljana is becoming cheaper” (Stanovanja v Ljubljani so se pocenila). While the messages conveyed were rather mixed, overall they suggested a stagnating market due to the lack of new housing being built and potential buyers unable to afford a property.

In the first half of 2018, the Geodesic Administration (GURS) recorded only 190 sales of new apartments – the primary market – a fall of 54% compared to the second half of 2017 and 62% less than seen in the first half of 2017. The primary market thus accounted for just 4% of all sales in the capital, while in 2015 this figure was around 12%, due to the sale of new housing stock from projects hit by the financial crisis. Moreover, Q3 2018 saw just 41 new apartments sold in Ljubljana, the lowest number since 2007.

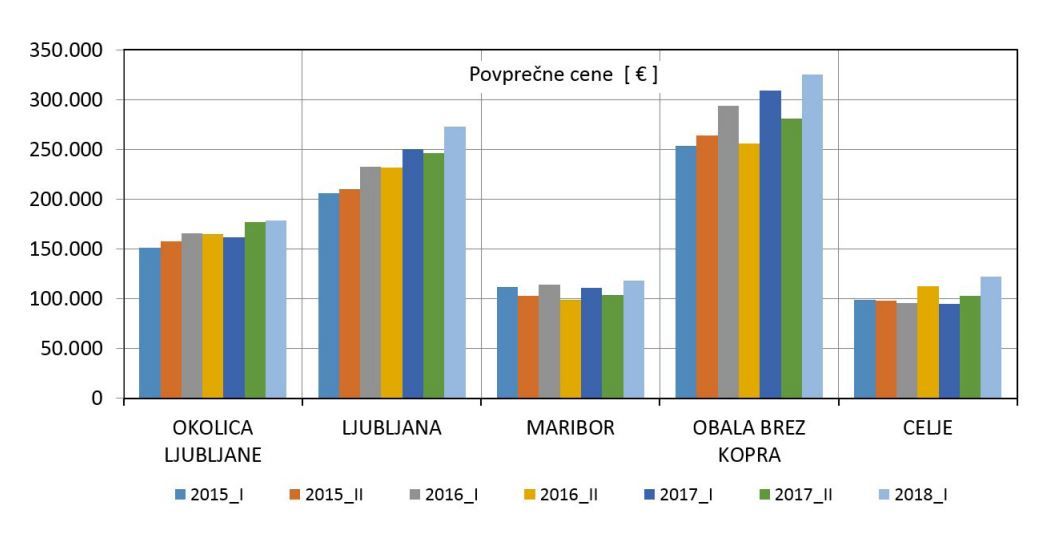

This figure, from GURS' report, shows the average prices of properties around Ljubljana, in Ljubljana, Maribor, on the coast (not including Koper) and in Celje, from summer 2015 to summer 2018

Since many purchases of new apartments in the capital require the sale of two or more older properties, this fall in the number of new units being bought has the effect of reducing the amount of used real estate coming on to the market, as noted by Boštjan Udovič, the director of the Chamber of Commerce for Real Estate at the Chamber of Commerce and Industry. Delo also reports that in Q3 2018 1,385 properties classed as second homes were sold in Ljubljana, 26% less than the quarterly average in 2016.

The article, which can be read (albeit in Slovene and behind a paywall) here, concludes with an uncertain forecast for the year ahead, stating that while the demand for housing does outstrip supply in Ljubljana, indicating some upward pressure on prices, if people are unable to afford a purchase then prices will eventually fall.

All our stories on Slovenia's real estate market can be found here, while you can watch a recent episode of House Hunters International about a family looking for an apartment in Ljubljana here.

STA, 9 January 2019 - Plastika Skaza, a Velenje-based company specialised in plastics products, last year exceeded EUR 40m in total revenues for the first time in its 40-year history, while pre-tax profit was up seven-fold to EUR 1.4m, the company announced on Wednesday.

Speaking to the press in Ljubljana, the management noted that revenues were up by 4% last year, adding that in 2019, Plastika Skaza intended to enter the German market and continue with investments in research and development.

"The goal for this year is to generate EUR 50m in revenue, driven by growing sales of our own brand, which currently represents 8% of total sales," sales director Mirela Kurt told the STA.

In this segment, the company gained 18 new clients and recorded sales growth of 70% last year, she noted.

The company employs 368 people and sells around 90% of its products abroad, mostly in Scandinavian markets.

Last year, Plastika Skaza invested a total of EUR 1.1m, mostly to machines and equipment, automation and development of a smart plant. This year investments are planned to stand at EUR 1.2m.

The company has abandoned production for the automotive industry and now focuses on the furniture and electronics industry, while putting an emphasis on biomaterials and recycled materials for its products.

STA, 8 January 2018 - The business newspaper Finance examines on Tuesday the remnants of the crypto craze that gripped Slovenia at end of 2017 and the beginning of 2018, arguing that "not much is left": several companies that turned to ICOs for funding went bust, while others barely live on.

"Not a single token [released in Slovenian ICOs] has managed to stay above the price with which they entered the crypto market. This means that anybody who participated in any Slovenian ICO project and has not sold its tokens, has lost their money," the paper notes.

There were many ideas in various fields, including banking, auditing, payment services, supply chains and car rentals, and some still persist, but "it is becoming crystal clear that they did not join the hype to solve the problems but because it was easy to raise funds".

"I do believe that the intentions of most crypto entrepreneurs were not bad and that they really wanted to do something good.

But their wish was powered significantly by the fact that they could play without their own input, that is with the funds of others," the paper goes on under Without a Light at the End of Cryptotunnel.

"If they would have had to take out a loan to embark on their business path, nine out of ten companies likely would not have had emerged," says Finance.

"On the other hand, many who left the cryptoparty in time got rich and earned enough in a couple of years to be covered for the rest of their lives. Some even entered the ranking of the richest Slovenians.

All out Bitcoin and crypto stories can be found here

STA, 7 January 2019 - Slovenia plans to issue a ten-year bond and has mandated Abanka, Barclays, BNP Paribas, Credit Agricole CIB, Commerzbank and HSBC to lead manage the new euro benchmark, the Finance Ministry said on Monday. Citing market data provider Bloomberg, the newspaper Finance reported the issue would amount to EUR 1.5bn.

"The deal is expected to be launched in the near future, subject to market conditions," the treasury said about the bond with a stated due date of 14 March 2029.

The issue would make Slovenia the first eurozone country to test the bond market this year, Finance reported citing Bloomberg.

Finance later reported that the order book, opened on Monday morning, contained offers worth EUR 3bn in the afternoon.

According to Bloomberg, Slovenia will borrow EUR 1.5bn at a price that is even somewhat lower than initially expected.

The yield on the current 10-year benchmarks is currently at 1.04%, 0.82 percentage points over the German benchmark, according to data from electronic exchange MTS.

The debt financing programme adopted by the government in December stipulates that Slovenia will issue fresh bonds worth a maximum of EUR 2.1bn this year.

Last year it issued fresh debt worth EUR 1.5bn and also refinanced dollar-denominated bonds to the tune of EUR 1.25bn.

STA, 4 January 2019 - Joc Pečečnik, the driving force behind the project to revamp a rundown Ljubljana sports stadium designed by Slovenia's best known architect Jože Plečnik, has not given up on the project just yet. After withdrawing a request for an environmental consent, he has filed for an integral construction permit, which is to speed up the project.

Although opponents of the project declared it dead and buried yesterday when it transpired that the investor, Pečečnik's Bežigrad Sports Park (BŠP), had withdrawn the request for the environmental consent, it seems that Pečečnik has only taken a new path to implement his plan.

Rather than pushing for the environmental consent as a precondition for a building permit, he has decided to request the integral construction permit under new legislation.

The Ministry of Environment and Spatial Planning confirmed for the STA that the BŠP had filed the request on 20 December in line with the amended construction legislation that stepped into force last year.

The procedure for integral construction permit combines the procedures of the environmental impact assessment and the issuing of the construction permit. The new legislation gives the ministry full power to decide on projects, completely leaving out the Environment Agency.

The procedure must also not take more than five months, not counting the period of public debate.

Neither Pečečnik nor the Slovenian Olympic Committee, which is involved in the project along with the Ljubljana municipality, would comment on the issue today.

The news first broke as the civil initiative that has been campaigning for the preservation of Plečnik's stadium in its original form announced on Thursday that the investor had withdrawn its request for the environmental consent, a precondition for a building permit.

The initiative welcomed the decision, labelling the move a sign that the project is now dead and buried.

According to the initiative, the investor too must have realised that the project was unacceptable because it would have caused environmental damage as well as destroy Plečnik's heritage. Pečečnik, the main investor, was unavailable for comment today.

But the head of the Olympic Committee, Bogdan Gabrovec, told the newspaper Delo last December that the renovation of the Plečnik stadium was a priority for him.

"It's a disgrace for all, for cultural heritage, the state and the city. The ten-year agony over construction plans, which are now in line with all environmental standards, has become harmful. This story must be solved one way or another in this term," he said in an interview.

If the project fell through, the Olympic Committee would lose some EUR 2.5m, which would plunge it into the red and that would be a big obstacle when applying to calls for applications, he said.

Ljubljana Mayor Zoran Janković told the press today he was convinced that Pečečnik was sticking with the project and that the civil initiative opposing the project had jumped to conclusions yesterday.