STA, 6 December 2019 - Following years of efforts by researchers, a project was launched to design the first monitoring of the most important wild pollinators - wild bees - in Slovenia. Their role has long been neglected even if they are more effective pollinators than honeybees. Slovenian scientists would like to better understand them, and to do that they will apply machine learning methods.

Pollinators are key to both agriculture and the preservation of natural ecosystems. Although honeybees used to be considered the most important pollinators, it has become clear that it is crucial to have a variety of pollinators; wild pollinators such as bumblebees are for instance more efficient pollinators than honeybees.

Due to their short tongue, honeybees tend to avoid blossoms with a longer neck, which are pollinated by bumblebees. Bumblebees are particularly important for plants which require blossom shaking to be pollinated, for instance key crops such as tomatoes and blueberries, and another 16,000 plants. They are also indispensable for plants with very deep blossoms, which honeybees cannot pollinate with their short tongue, said Danilo Bevk from the National Institute of Biology.

Bumblebees are also special in that they fly around in bad weather, which is quite often the case when fruit trees are blossoming in the spring. "This is one of the reasons why we could say that they are the most important wild pollinators, although others, such as solitary bees, flower flies or butterflies are also important," said Bevk.

Keeping bumblebees as a hobby

While beekeeping is a very popular pastime in Slovenia, bumblebee-keeping is much less widespread, with only slightly more than 180 people keeping bumblebees in their gardens. One of them is Janez Grad, a doctor of mathematics and retired professor emeritus of computer science of the Ljubljana Faculty of Economics, who has had bumblebees in his garden behind his home for 35 years.

Every year about seven species of bumblebees find their home in his garden. "Queen bumblebees fly back to their hives after hibernation, just like swallows come back to their nest," said Grad.

Only bumblebee queens hibernate

Bumblebee hives in Grad's garden are empty in the autumn, as the animals go into hibernation, which usually lasts seven months. Only bumblebee queens from the past season survive winter, having dug into soil in the woods, away from people, animals and light, hibernating until early spring when new bumblebee families, worker bees, male bees and new bumblebee queens emerge.

The development of a bumblebee family depends on weather. If spring arrives early, new bumblebee families can appear at the end of February. But an early and warm spring followed by a cold spell disaster. In this case bumblebee queens leave their nest, leaving behind their brood. Once they return after the cold spell is over, it is often too late. This year May was cold and rainy, which Grad, one of the greatest experts on bumblebees in Slovenia, said would be felt next year.

People, disease and climate change pose a threat to bumblebees

Climate change is one of the most serious threats to bumblebees and will affect the majority of bumblebees in Europe. Researchers expect that as a result of anticipated climate changes, almost half of all bumblebee species could lose 50-80% of their territory by 2100, said Bevk.

"However, for some species changes will be an opportunity. A Mediterranean bumblebee spread here a decade ago probably due to climate change. Climate change will of course have a negative impact on pollination, so it is even more important to preserve a high degree of diversity of pollinators."

Various diseases, and some birds which eat bumblebee queens in spring, are another threat to bumblebees. However, Grad said that people are enemy No. 1 of bumblebees, destroying their habitat with intensive agriculture, frequent and early grass cutting, and with the use of pesticides.

First monitoring of solitary bees and bumblebees

Sixty-eight species of bumblebees have been discovered in Europe, of which a quarter are at risk of extinction. Half the populations are in decline, Bevk explained. There are 35 species in Slovenia, and while some of them have not been noticed for quite a while, their extinction cannot be proved because there has been no wild bee monitoring in Slovenia yet.

In November, after five years of efforts by researchers, a project was launched to design the monitoring of wild bees - solitary bees and bumblebees - in Slovenia.

"The project aims to develop a methodology of wild bee monitoring, launch test monitoring at selected locations, assess the situation of wild bees and draft guidelines for sustainable monitoring of wild pollinators in Slovenia," explained Bevk.

The National Institute of Biology, which is in charge of the project, believes this will enable them to gather hard data about the movement of bumblebee and solitary bee populations in our country, which is of key importance in designing adequate measures to protect and monitor the efficiency of these important pollinators. Regular monitoring could make Slovenia a leader in this field in Europe, the institute said.

Machine learning to study bumblebees

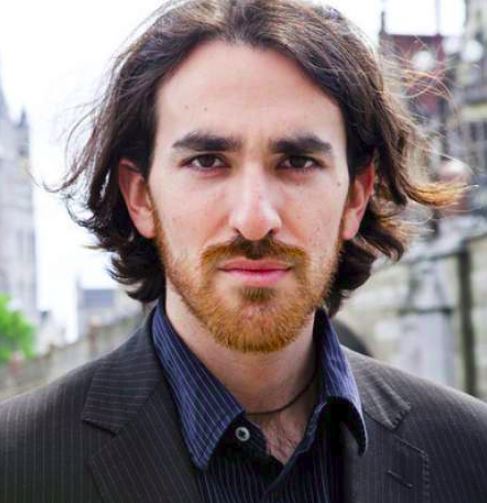

An important contribution to better understand bumblebees has been made over the past few years by researchers from the Jožef Stefan Institute's department for intelligent systems, which has been researching buzz sound and temperature in close collaboration with Professor Grad.

Grad contacted the Jožef Stefan Institute a few years ago asking for help in analysing the bumblebee buzz which he had recorded in previous seasons, explained researcher Anton Gradišek. With the help of Grad's recordings, the institute developed an app which draws on machine learning and which, using advanced computer methods, recognises which bumblebee species makes which buzz sound, and whether the sound is made by a queen or worker bee.

Researchers at the institute are not the first to study bumblebees, but their research is different in that it is carried out in nature, in Grad's garden rather than in a controlled lab environment. Gradišek said the garden proved to be an excellent natural laboratory, enabling them to study not just a few of the most interesting species but a number of different ones.

The institute is researching different aspects of bumblebees, including sound and temperature. Sound research has resulted in a new simple method to record bumblebee flight to establish when bumblebees are more active, which depends on the species.

As part of the research into temperature, small temperature sensors and thermometers are put in hives to monitor how well bumblebees can keep temperature, which is important for the development of larvae. If the temperatures is adequate, the larvae develop properly, whereas an environment too hot or too cold affect the development of the colony.

"The research has shown that we can recognise different species of bumblebees quite well, which is important for further studies of biodiversity. The temperature research is interesting from the aspect of climate crisis and its impact on the development of bumblebees," said Gradišek.

The researchers would also like to study communication in the nest, for instance how bumblebees let others know the location of the food in the nest, which bees do with waggle dance. They would also like to know how changes in temperatures in the nest and its surroundings affect their activity.