John Bills is the author of four books on Europe's better half, electronic versions of which are currently available at special lockdown prices, including a great deal on all four - just under £10 (or just over €11) for the lot with the promo code ENDOFDAYS at poshlostbooks.

Slovene history is littered with no shortage of talented writers. Quite the opposite, in fact, and I’d wager that this small chicken-shaped land has produced more wordsmiths per square kilometre than any other country in Europe. Fertile ground for the eloquent, that’s for sure. Every period of the nation’s history features men and women who have excelled in storytelling, taking the events and circumstances of the time to fashion tales that are as vital today as they were then.

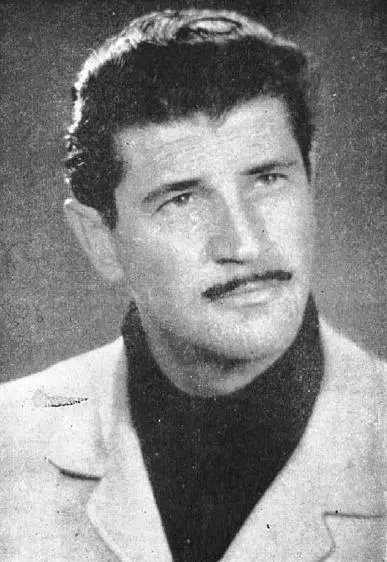

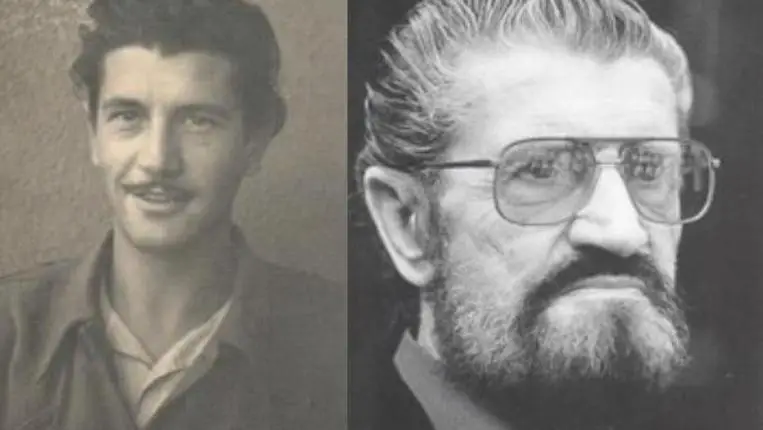

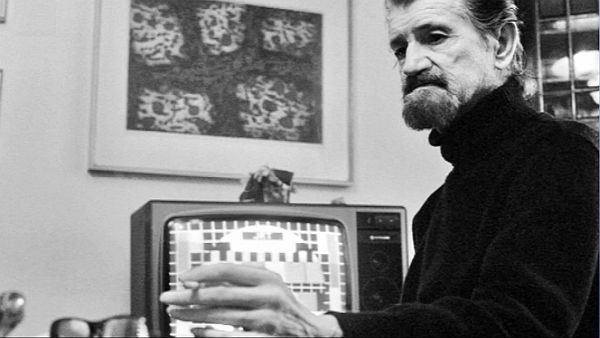

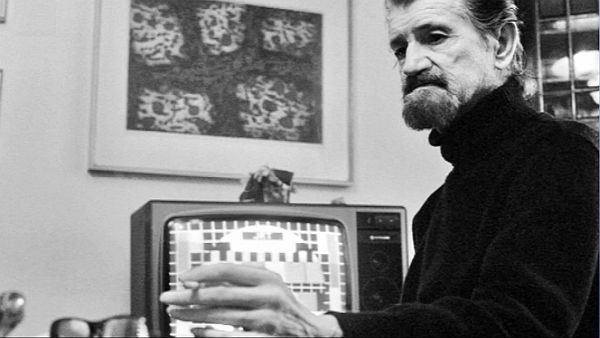

The writer has many jobs, many roles that must be played in the theatre of everyday life. Entertainers for sure, there must always be an engagement, but books go beyond mere titillation. Ljubljana-born Vitomil Zupan said it best in Leviatan (Leviathan [obviously]), an epic piece of work that details the day to day existence inside a Yugoslav prison; “…the wordsmith must be a chronicler of his times, and a chronicler must not be disgusted by anything”. In Zupan’s era, there was a lot to be disgusted by, but the modernist man turned his nose up at not a thing. In doing so, he became one of Slovenia’s most celebrated 20th-century writers, a man famed for his unwavering obsession with the edges of existence, his rapacious sexual appetite and a steely charm that positively bellowed “Hi, I’m your mum’s new boyfriend”. His life was eventful in all possible ways, but it was also a fascinating picture of Slovene creativity in those early Yugoslav days. Stigma, expression, productivity and oppression, repeated.

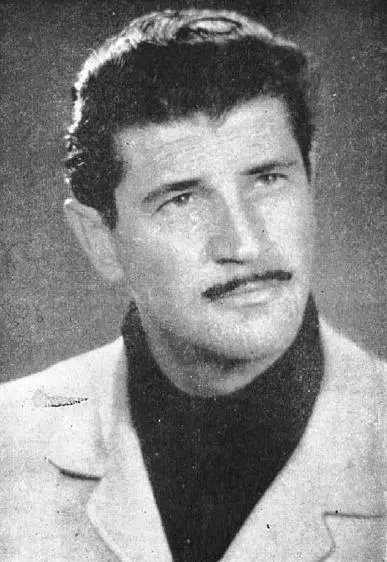

Vitomil Zupan was born just a couple of months before World War I began, and it didn’t take long for his life to encounter turbulence. His father was an officer in the Austro-Hungarian Army, and the Habsburg force had a pretty wretched record over the first years of the Great War. Casualties were high, and Mr. Zupan was one of the dead. Young Vitomil lived through the war and was a creative schoolchild, but his restlessness and ability to seek out trouble often, well, got him into trouble. The apex of this was a game of Russian Roulette gone wrong, a game that took place when Vitomil was just 17. His hand was on the trigger, his friend’s body was at the end of the barrel, the chamber was loaded. Russian Roulette is one of the few games that go wrong by going right. Zupan was expelled from school (a fairly light punishment, in hindsight), and he chose to hit the road.

Vitomil travelled long and far, crisscrossing the Mediterranean in search of new experiences and fresh excitement. His was a true vagabond existence, jumping from city to city and job to job, meeting people and moving on as often as was necessary. He worked as a sailor, a house painter, a ski instructor and more, even having a stint as a boxer. A strong jaw will take you far, never forget that. Zupan moved from Europe to the Middle East and North Africa, learning languages, cavorting with foreigners, learning how to thrive in new environments and in unfamiliar surroundings. Remember kids, if you can travel, travel.

Zupan returned to Ljubljana and continued his education, but he spent more time studying medical textbooks than concentrating on his own studies, feeding a constant need to understand his own emotions and tumultuous moods. The latter was dramatically exacerbated by the onset of World War II, which makes a lot of sense. Zupan immediately joined the Liberation Front and fought against the Italians, experiencing a number of battles before being captured and arrested. He was first sent to Čiginj concentration camp (near Tolmin), before being moved to the newly-opened Gonars camp in the north of Italy.

Established in February 1942, Gonars was a fascist camp specifically for Slovenes and Croats, people the Italians deemed ‘inferior’ and ‘barbaric’, those living in borderlands that Mussolini had his seedy eyes and grubby hands on. 5,343 men, women and children (1,643 children, to be precise) arrived just two days after it was opened, and the transports continued from there. Some of history’s most notable Slovenes were among them, men such as Jakob Savinšek, Bojan Štih, France Balantič and many more. Vitomil Zupan was another.

Vitomil Zupan managed to escape Gonars, and he immediately joined the growing Partisan movement Slovene, initially fighting on the frontlines before moving into the cultural department. He wrote plays that championed the socialist cause, encouraging Yugoslav patriotism in his fellow fighters and providing much-needed escape along the way. Following the war, he was rewarded with honours and a position at Radio Ljubljana, before the holy grail of a Prešeren Award for his novel ‘Birth in a Storm’ in 1947. Then Yugoslavia and the USSR had the big falling out, and it all went to the dogs.

Zupan himself put it best when he said that ‘there comes a time when one man can ruin ten people, but ten people can’t help one man’. The split filled Yugoslavia with pride, it was making its own way after all, but it also filled the halls of power with neurosis and paranoia. The national liberation, the class revolution that followed and the eventual split from the Soviet Union, these were holy subjects that were nigh on untouchable. Zupan was one of the few people honest enough to mention the shades of grey, to point out that everyone can be involved in a revolution but not everyone becomes a revolutionary, which explains the prisons. Those prisons would soon host Vitomil Zupan.

Truth be told, he was an easy target. He was a controversial cultural figure, one who was openly and passionately in touch with the more erotic desires of the mind, a man who had travelled extensively, spoke multiple languages, was comfortable in the presence of foreigners and was ruggedly handsome to boot. Oh, and that whole ‘shooting his friend’ thing. Zupan was sentenced to 15 years in prison, a term that was almost immediately increased to 18 because of his conduct in court. To prison he went, less for his ideas and more for who he was, what he knew and who he knew it about. There was no evidence, and barely any more of a defence.

Zupan only served seven of his 18 years, but don’t make the mistake of thinking that the experience was full of cheer. His already-compromised health took a turn for the worse, and for years he wasn’t allowed to read or write. He worked around these restrictions through character, ingenuity and how poorly-policed the jails were, compiling enough ideas and notes for one of his most famous pieces of work. Published in 1982, Leviatan (Leviathan) is a narrative of this time in prison, a torturous study of humanity that covers day to day atrocities, sexual frustration and release, violence, boredom and no small amount of black humour. The novel doesn’t really have a story outside of ‘this is what life is actually like in prison’. It is a vital piece of work.

Zupan’s major break came seven years prior, with the much-loved Menuet za kitaro (A Minuet for Guitar). This novel focused on his time in the war, a book based half during that conflict and half in the more relaxed atmosphere of a 1970s Spanish holiday resort, where soldiers from opposing sides (a Slovene Partisan and a Nazi) try to make sense of the whole thing. It covers all sides and all interpretations of the war and is every bit as ambitious as that suggests, and features one of the most pathetic, banal, poignant and perfect character deaths in the history of conflict fiction. It was adapted for film in 1980, given the new moniker Nasvidenje v naslednji vojni (See You in the Next War) in the process. A second Prešeren Award came in 1984, this time for his entire body of work.

There is a disjointed feel to Vitomil Zupan’s life story, a collection of contradictions that only seem to happen to those tasked with chronicling history in fictional form and blessed with the ability to do so. He was arguably more successful than any other persecuted writer from what was Yugoslavia. He won awards, experienced commercial and critical success, yet no publisher would go near his work in its original form. He wrote the most expressive Slovene books of his generation, but almost all of these works were heavily censored by the humdrum and the grey. He lived a life of tumult, adventure and penury, but everything seemed to happen to him so that he could write about it.

Vitomil Zupan died in Ljubljana on May 14, 1987 (the same day as Rita Hayworth, believe it or not). One of Slovenia’s most important and influential modernist writers, he is to the Slovene literary canon what Hemingway and Solzhenitsyn are to the west, combined. Such lazy comparisons are often difficult to avoid, especially when the stern eyes and imperturbable moustache of Vitomil Zupan, your mum’s new boyfriend, gaze in your direction.

John Bills is the author of four books on Europe's better half, electronic versions of which are currently available at special lockdown prices, including a great deal on all four - just under £10 (or just over €11) for the lot with the promo code ENDOFDAYS at poshlostbooks. You can enjoy more of his work on Total Slovenia News here.