This summer, and until October 13, visitors have been able to experience a very unusual show held in the basement of the Slovenian National Gallery. The exhibition Alan Ford Runs a Victory Lap (Alan Ford teče častni krog) marks 50 years of the Italian comic book named Alan Ford and consists of 162 original boards created by a writer Luciano Secchi – aka Bunker – and artist Roberto Raviola – Magnus – in the years between 1969 and 1975. As the gallery proudly announced, this is the largest exhibition of Alan Ford boards so far, much bigger than the one in Rome which only displayed 30 of such originals.

So how come an Italian comic book has found its way to the Slovenian National Gallery, a place reserved for classic paintings, olds statues and even the original Robba Fountain, that was removed from the Town Square to protect it from rain and other damaging environmental influences?

One of the reasons for this lies in the fact that the comic was much bigger in Yugoslavia than it was in the land of its origin. Not that Alan Ford wasn’t popular in Italy, it’s just that in Yugoslavia it became a cultural phenomenon spread across the entire federation. As Izar Lunaček, a comic book artist commented on Alan Ford in an interview for a national broadcaster, artists from the former Yugoslavia are a bit of fed up with it, since every time they tell someone what they do for a living, the response is always the same, “Oh, I read Alan Ford!”

According to its writer, Bunker, Alan Ford draws on an old art form called commedia dell’arte set in a Cold War situation. The plot consists of a group of anti-Bond characters, who under the official name TNT group run secret government operations from a flower shop in Brooklyn, New York, a cover for their headquarters.

The characters, just like actors of commedia dell’arte, represent fixed social types. To name few of the group’s members:

Alan Ford is a naïve and handsome young man with a troubled love life, drawn to look like the British actor Peter O’Toole.

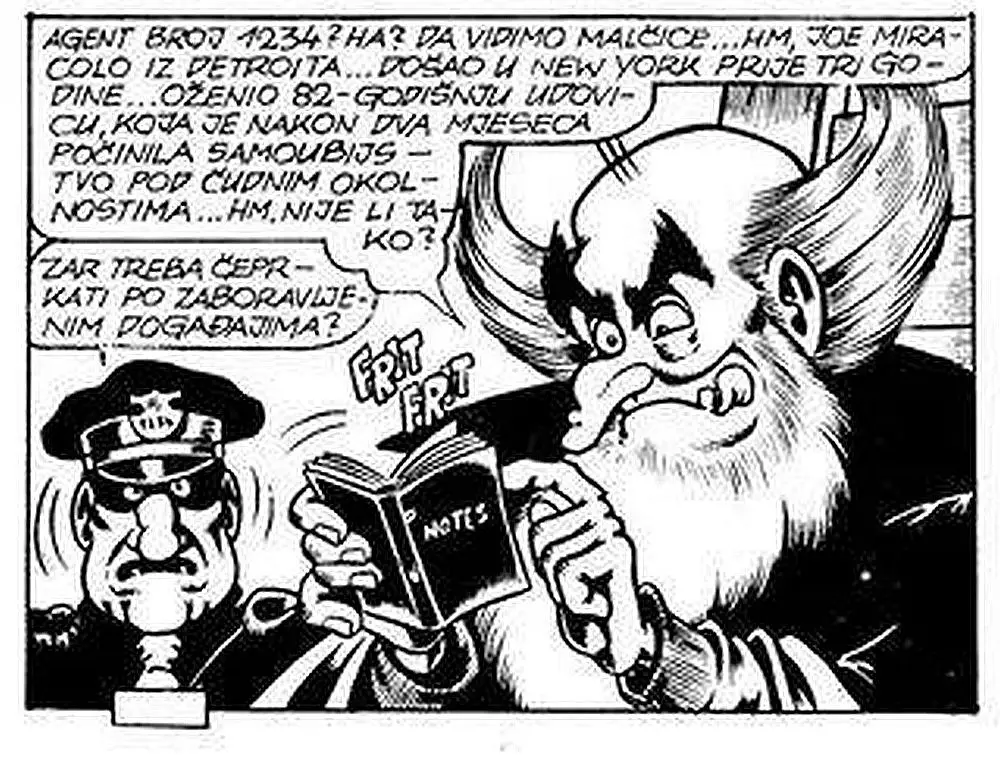

Number One is a cunning old man in a wheelchair, who is in charge of their secret operations. He is in possession a little black book full of compromising information on pretty much everyone, so it seems. He is also very miserly and keeps his agents in a state of constant poverty. He likes to tell them his life story, such as the role he played in Ancient Rome or the American Civil War.

Sir Oliver is an English nobleman and a kleptomaniac, who manages to steal something in every episode, then calls his friend to sell the goods, repeating the line: “Price? A bargain.”

Bob Rock, from a family of criminals, is a very short agent with a quick temper and a large nose, which is the subject of many jokes (which then cause him to lose his temper). Bob Rock is also the most outspoken of the group when complaining about the poor working conditions they have to endure.

This is the decisive moment: better to live one hundred years as a millionaire, than one week in poverty!

Otto von Grunf is a German-born inventor, now a naturalised American, who fought in WWI and, as suggested on many occasions, in WWII as well. A coward full of false bravado he is in charge of the group’s gadget development, although these devices are mostly useless or make little sense.

On the side of the villains the one worth mentioning is Superciuk (in Yugoslavia known as Superhik), or Superdrunk, a man who “steals from the poor to give to the rich”, a super anti-hero whose main weapon is his deadly breath, alimented with poor quality Barbera (wine) and onions. In ordinary life, Superhik is a street-sweeper.

There have been numerous attempts at explanations of why this comic book was so big in Yugoslavia while other translations fared poorly. On reason why the comic didn’t succeed in other countries could certainly be found in the market. It could also be argued that perhaps other translations weren’t as masterfully done as Nenad Brixy’s, under the pseudonym Timothy Toucher. Brixy was also the person mostly responsible for introducing of the comic to the Yugoslav market in 1970, as the man not only found the comic in a shop in Trieste, but translated it into Croatian and as an entertainment editor of Vjesnik secured its publication. When a Slovenian translation emerged in 1993, it was accepted with mixed reviews, some people still continued to prefer the “original” Croatian version.

But this doesn’t explain why Alan Ford gained such a cult status among the Yugoslavs, who en masse identified with the absurdism of the comic.

In part the question was answered by the author, Bunker, himself, who has linked the comic with the tradition of commedia dell’arte.

In this 16th century theatrical form, actors play characters who represent fixed social types and as such improvise on a pre-set plot. Interestingly enough, such improvisation takes much more work than a fully scripted play would, as it involves a lot of practice using various contingency based on reactions from the audience and other actors.

Several scholarly articles have noted that such practice is in fact required from players of every democratic regime. However, “Whereas in English theatre the drama was built around personalities, in commedia dell'arte the characters were subordinate to the plot, as is also the case in democratic politics.”

Commedia dell’arte evades the modern notion of identity as a quest for authenticity in which a “true” self, distorted by a social role-playing, needs to be discovered and exhibited. Instead, role-playing is what constitutes the creation and re-creation of the reality, or “the truth”.

In an interview for the national broadcaster, Marcel Štefančič thus explains: “Why would you have a feeling that all of this was taking place in Yugoslavia? To be a Yugoslavian, that was a role. A Yugoslavian was constantly aware of the fact that they were playing a character. A Yugoslavian was always aware that they were playing a role and they accepted to play that role. They were aware of the gap between their mask, between their acting and the social reality. But they continued to act … These characters in Alan Ford, someone might think, were some sort of Yugoslav dissidents. No way, it was the other way around. A Yugoslavian dissident was certain that behind the mask, there exists some genuine truth. No, these Alan Ford characters lived in no illusion with regard to the fact that even the truth is only a mask.”

Or, to conclude with another quote, from Lazar Džamić, a researcher of the Balkan Alan Ford phenomenon, “Our natural environment, our system of social organisation is not socialism or communism, it is surrealism. This isn’t an art form, it’s what we’ve lived.”

And thus Alan Ford remains, in newsstands, secondhand bookstores and homes across the former Yugoslavia, a window into a world that once was and in many ways continnues to be.