Meet the People

How did you come to live in Slovenia?

I moved to Slovenia in March 2018 to be with my fiancée, now wife, Anita, who’s a Slovenian national. I first met her via Couchsurfing in 2015. She asked me many questions about travelling around India. Unfortunately, we never met up at that time as I was out of Delhi on a tour, however we remained in contact. At the end of 2016 we arranged to do a month-long yoga teaching course in Rishikesh together and from there on it was a bit like a Bollywood movie … love at first sight!

After the course we did some motorbike touring up into Nepal before Anita returned to Prague. In 2017 she returned to India again for six months, during which time she lived with my family. Eventually, I joined her in Slovenia in March 2018 and we got married in India a year later, then came back to Slovenia in April to make our lives here.

What work have you been doing here?

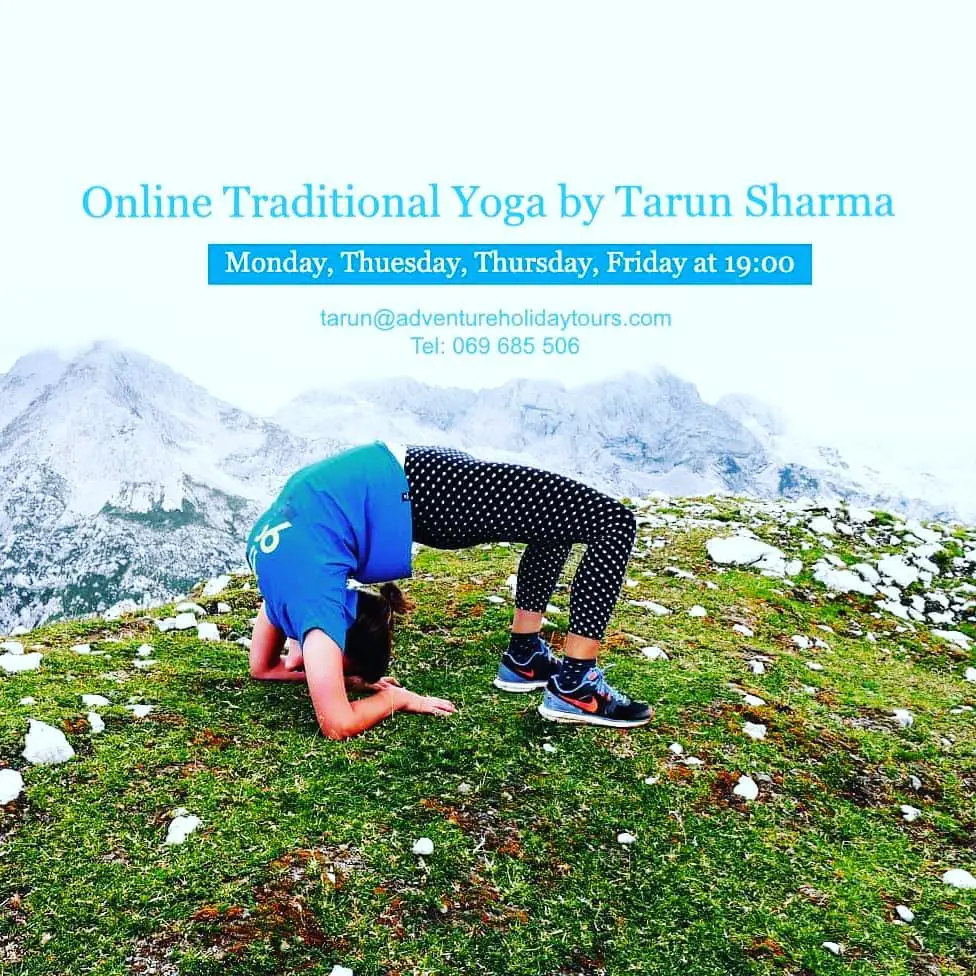

Before COVID I was driving tourists around Slovenia, teaching yoga, Indian food cooking and Ajurvedic massages. I got into the first business in India, where my family has a travel agency, Adventure Holiday Tours in Delhi, India. Back home my work was to show visitors around the India organize their tours with our private English-speaking drivers. Our company has a great team of drivers, and a very good reputation online because we made sure that everyone enjoyed their tour with us. So when I came to Slovenia I started a similar company after I received my work permit – Adventure Holiday Tours, Tarun Sharma.

How was your business affected by the pandemic?

Since April last year we’ve only had three to five of giving tours in total for Slovenia. Luckily I was able to get the COVID support from the government since October, and I’ve been giving online yoga classes. However, this has badly affected our family business in India, as since April last year the country stopped tourist visas and nobody’s been coming to visit. And so no work for the drivers who’ve been working for my fathers company in Delhi, India.

Yes, you now have a project to help the drivers – can you tell us about that?

Sure, I’m trying to help the drivers and their families who’ve been working for my dad’s company over 10 years in India. They’ve been great to all the tourists visiting India and making sure they enjoyed their stay. Now since April last year they haven’t had any work. My dad helped them, but he also doesn't have any work now and so I want to raise some funds for them so that we can help them to open some other business and make a living until tourism starts again.

How can people learn more?

Here’s a link where people can read more, and also make a donation or just share the link to spread the message. Even just €10 provides a lot of help. https://www.ketto.org/fundraiser/families-in-need-due-to-no-foreign-tourism-in-india

STA, 7 February 2021 - Marko Mušič, one of the most distinguished Slovenian architects, comes from a long line of architects. He will receive the Prešeren Prize for lifetime-achievement, the country's top accolade for artistic accomplishments, after leaving a notable mark with his work in Slovenia and throughout the former Yugoslavia.

Five of Mušič's ancestors were architects, including his father Marjan Mušič, which he sees as a privilege. He told the STA in an interview that he "simply worshipped" his father, who was a "refined art connoisseur, a profound architectural theorist and historian, an excellent project manager, a classic of the Slovenian architectural drawing and of course a prolific and extraordinary writer".

Mušič (1941) graduated in 1966 under the mentorship of professor Edvard Ravnikar, who just like Mušič's father was a student of the great architect Jože Plečnik (1872-1957). He continued his studies in Denmark and the US, where he cooperated with architect and archaeologist Ejnar Dyggve and with US architect Louis Kahn, respectively.

Kahn left a deep impression on Mušič. "I was drawn to his philosophy of architecture and in particular his honouring of tradition and the culture of architectural history," he told the STA.

"The clarity of his architectural composition and the sense of symbolism have always stood out. He was unlike anybody else and his architectural designs were such as well. He designed few buildings, but they were all in line with his motto that you must give each building a soul."

Mušič considered staying in the US, where opportunities for architects were immense, but Kahn "convinced me to go to Skopje immediately and continue and finish my great and important work there," he said in a reference to his work in the Macedonian capital.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Mušič left his mark in former Yugoslavian cities from Zagreb through Belgrade to Skopje and Bitola. "That was a period of enthusiasm, faith in the architecture, youthful zeal, new opportunities and of course competitiveness," he told the STA, saying Slovenian architects had been particularly esteemed in the former Yugoslavia.

He said architecture had had full political support at the time. "Interestingly, I was never asked why I'm not a member of the League of Communists or persuaded that this was needed if I were to be the chief architect."

In the 1980s, he started focussing on Slovenia. This was a time when Postmodernism radically ended the period of Modernism and Jože Plečnik was "rehabilitated". Mušič was strongly affected by this and his architectural language started containing elements of classical architecture although using modern material and showing his own personal style.

He has a strong connection to Plečnik. "My relationship with Plečnik has in particular a creative charge. Every one of his works, designs or sketches spontaneously reveals creative saturation, which is an inexhaustible source of interest, admiration and also new creative encouragement."

Mušič's most important projects in Ljubljana are the Ljubljana railway station, the Incarnation Church in the Dravlje borough, and the New Žale Cemetery. He is also the author of the Teharje memorial park dedicated to the victims of post-war killings.

Three of his projects, including the New National and University Library, Apostolic Nunciature in Ljubljana, and the Ljubljana passenger terminal have not be realised, which he said "left a slightly bitter aftertaste".

He feels particularly close to memorial architecture, which he focussed on in the 1990s. "When designing such projects we must be aware of Wittgenstein's belief that the meaning of ethics and aesthetics is to reveal the inexpressible ... We must be aware that every part of this space has its symbolic and ritual function."

Mušič is lauded by the jury conferring the Prešeren Prize for his unique architectural path, his "particular, at times controversial perspective standing against the 'flow of the time' and architectural trends, and which still aspires to 'architecture for all times'", something Plečnik had set high standards for.

Active in architecture in Slovenia and the broader Balkan region for almost 60 years, Mušič has a special place in this space and has been considered a wunderkind, the Prešeren Prize jury said. He has received several awards, including the Prešeren Fund Prize for outstanding achievements, and the Plečnik and Valvasor awards.

The latest international recognition of his work was the inclusion of his works in the big exhibition of Yugoslavian architecture in MoMA in New York in 2018.

He is a full member of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts (SAZU) and the European Academy of Sciences and Arts (EASA) and a corresponding member of the academies of sciences and arts of Republika Srpska, Montenegro, Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina.

"All awards are pleasant companions, but the Prešeren Prize of course has a special significance and ring to it. On the one hand it is a recognition for past achievements, but it is also an encouragement for the future, as even those of us who have walked a long way already are optimistic about the future and new challenges," he said.

STA, 7 February 2021 - Feri Lainšček, a writer, poet, playwright and screenwriter from north-eastern Slovenia, who will receive the Prešeren Prize for lifetime-achievement, sees his work not as a job but as a way of life. He believes literary heroes are spiritual beings with lives of their own.

Born in the hilly part of the Prekmurje region near the Hungarian border in 1959, Lainšček spoke and listened to nothing but dialect until primary school. In his first book from a trilogy about his life, Kurji Pastir (The Chicken Shepherd), which was published last year, he writes about the poverty he was born into and the immense love of his parents.

"I've always thought my mother and father have managed to build a kind of invisible bridge that I used to get out of that and somehow made it into a normal life," Lainšček told the STA. "While writing this novel, I finally realised this bridge was actually made of love."

He believes he has had "a kind of different childhood which taught me early on how to defy despair". After finishing secondary school in Murska Sobota, he wanted to study art in Ljubljana but failed to get accepted at the Academy of Fine Arts, so he opted for what is today the Faculty of Social Sciences.

He came to the capital "with nothing, like many others probably, at the time" and "had to start from scratch". "I had no acquaintances, relatives, godfathers. I actually got the most help from older writers I slowly got to know and started spending time with."

He described this period of his life in the novel Peronarji, with which he entered the literary world in 1982. During that time, he worked for Radio Ljubljana, and wrote poems and novels in his spare time.

He has written more than 100 books, including 30 novels. Many of his works have been translated into several foreign languages, and some have been also made into films. As author, Lainšček also cooperates with Slovenian musicians, most notably with young singer-songwriter Ditka.

"I must admit that things have just happened for me and Ditka and we never wondered whom we should thank for that ... No matter what it was, it is important that, spontaneously, we were on the same page, got closer in a creative way but also gave each other all the freedom. I believe the listeners sense that."

Lainšček has received many awards for his work, including the Prešeren Fund Prize for his novel Ki Jo Je Megla Prinesla (She Who Was Brought by Fog) and the Kresnik award for the best novel of the year for Namesto Koga Roža Cveti (Instead of Whom Does the Flower Bloom).

Six of his books were made into films, including the 2007 blockbuster Petelinji Zajtrk (Rooster's Breakfast), directed by Marko Naberšnik. "Luckily I learned early enough that the literary and film languages are very different. I realised that directors do not come to me because they wish to 'translate' my work but because they want to create something of their own."

He also publishes his poems on social media, so he did not have to move online when the epidemic started. "I have been there all the time. I've always been interested in new media and different carriers of message. I've been among the first ones to try a lot of things and I sometimes also used them conceptually, so I must say I don't see this as an emergency exit."

Lainšček receives the Prešeren Prize for his novels, poetry collections, short stories, books for children and youth, screenplays and radio plays. "Lainšček's literary achievements with their high artistic value have been significantly enriching the treasury of Slovenian culture for almost 40 years," the jury said.

He is lauded as the "leading poet and writer of Panonian Slovenia, whose works portray the lives of ordinary people from the margins of society in a very sensitive manner". By showing the "lyrical Gypsy soul", he is expressing respect to those who are different, the jury said.

His poetry is described as a mixture of Panonian melancholy and a personal vision of love. His works in Prekmurje dialect have significantly contributed to the building of bridges between Slovenia and the Slovenian community living in Hungary.

Lainšček is known to empathise deeply with his literary characters. "I hope this doesn't sound too mystical but I believe that literary heroes are in fact spiritual beings. We the writers create them and then they live their own lives, often outside their books. For example, Martin Krpan has never lived, he was created by (Fran) Levstik, yet he is still around and we all know him."

He sees the whole creative process as a dialogue where literary heroes have free will, "so I usually don't know until the end how the story will unfold".

In the case of Muriša, a young woman who is the main character of Lainšček's namesake book, the author says he tried very hard to save her but in the end she died anyway because she followed her beliefs and ideals blindly.

"I remember winning Kresnik for that novel. The award ceremony was at Rožnik Hill more than a year after I finished the novel but a single thought occurred to me there. Muriša did not die in vain after all. Everyone expected me to be happy about the prize, but I was so moved I nearly cried."

The Prešeren Prize will, however, be different. "I am very happy to win it and I accept it with respect. I have won it for the work that I have been devoted to with my body and soul since youth. It has become my way of life and in a way affected everything I have ever done."

Goran Vojnović came to prominence with his first novel, Čefurji raus! (2008), translated as Southern Scum Go Home!, which explores the lives of immigrants from the former Yugoslavia and those of their children in Ljubljana’s Fužine, a group commonly known as čefurji. It’s a work that essential reading for anyone interested in Slovenia and wanting to lift the lid on the chocolate box images that dominate foreign representations of the country.

He followed this up with Jugoslavija, moja dežela(2011) (Yugoslavia, My Fatherland), a work that deals more directly with the disintegration of Yugoslavia. His most recent novel is Figa (2016), which on 20 October is released in its English version by Istros Books (and translated by Olivia Hellewell) as The Fig Tree. We’ll have something more about that next weekend, but for now here’s an interview with the man himself…

How doe The Fig Tree stand in relation to your first two books?

I once said that my first two novels were two screams, while The Fig Tree is a silent exhale. It is a different, gentler novel, I think. With first two novels I addressed two things that define me most as a person. Growing up as čefur and Balkan war. I think I just had to cry it out so I can become a real writer, to be able to put literature in pole position while I am writing. The Fig Tree is dealing with topics of my first two novels – I will probably stick to them to the very end - but in a different way.

The Fig Tree is set on the coast, in Istria, is that an area that you have a personal connection with?

My mother is from Pula and I've spent a big part of my childhood there. Istria is therefore inseparable part of my homeland, my novel The Fig Tree is not just set there but is actually made from my memories of Istria and my family, it is born out of feelings Istria awakens in me. There are also many places in Slovenia where I feel at home, but it is difficult to say where I am happiest. Happiness is not about places for me. In Ljubljana I was probably happiest, but I had also my worst time there.

Our readers are interested in Slovenia, but usually can’t understand Slovenian to a high level yet. What are some of the culture products you’d suggest they pay attention to as they learn more about the country?

Slovenia is not so easy to understand and one should never underestimate its diversity and its paradoxes. It is a ridiculously small country but one with extraordinarily rich cultural influences. We lie on a great crossroad of Roman, German and Slavic world, with gorgeously rich Hungarian culture in the east. On top of that, we were on the frontier between socialist East and capitalist West for almost half a century. To be honest, I think that we are still searching for our own identity, trying to figure out who we are, so be patient with us, please.

With all that said, you should read Prišleki (1984) (Newcomers: Book Two) our greatest novel by great Lojze Kovačič, which is by far the best take on our complex contemporary history.

The novels of Andrej E. Skubic [such as Fužine Blues] and films from Damjan Kozole [Slovenka (Slovenian Girl); Rezervni deli (Spare Parts)] successfully deal with transition and its consequences, one topic that is in my opinion proved to be the most difficult to deal with.

The whole film, with subtitles and in better quality than the trailer, is on YouTube here

But if you are here for the art, then search out the books of Dušan Šarotar or Matjaž Ivanišin's films. Or poetry from Esad Babačić, Katja Perat, Anja Golob and many other great Slovenian poets. I love how late Metka Krašovec paints silence or sublime sculptures of Jakov Brdar. I love Severa Gjurin's magical voice and Pannonian melancholy of Vlado Kreslin's music. And once you master the Slovenia language you should definitely listen to Iztok Mlakar, our greatest storyteller. And yes, Špela Čadež's short animations are also a must.

I could go on or write completely different list, of course, but let's stop at that.

You're also a very well-respected screenwriter and director. To ask a question that was going around Twitter: Netflix called, offered a huge budget and gave you creative freedom for a limited series about Slovenia, set in any time – what period would you focus on?

Well, if they offered me a really huge budget I would definitely shot Lojze Kovačič's Prišleki. It would be a great TV series. And I would cast the best Slovenian actors which in my opinion are as good as any in this world.

How would you like to see Slovenia change over the next decade or two, and do you have any optimism this will happen?

I am not optimistic person but judging from your last two questions you really want me to imagine unimaginable so I could say that I would like Slovenia to calm down its own adolescent political hysteria and I would love if our professional environment would become professional indeed. I would also love if we would finally get a proper public transport so people could start using it daily when travelling between cities. I also hope that our everyday life stays as relaxed as it is and that we will continue to cherish our free time as we do now.

What are you working on now?

As always, I am working on many things. I am preparing the release of my new feature film Once Were Humans, while also working on a documentary about Eurobasket 2017. I am finishing my new novel too.

You can pre-order a copy of The Fig Tree from Istros Books, and find Vojnović's other titles in bookstores or online

Nataša Tovirac is a dancer, choreographer, dance pedagogue and yoga instructor. She joined Intakt Dance Studio 27 years ago and became its sole Artistic and Programme Director in 2007. Under her professional guidance Intakt continues its mission of quality dance education and openness to the broader public, while managing to remain an elite contemporary dance institution in Slovenia.

Nataša, who can join your dance studio and what kind of classes are currently taught at Intakt?

Since our inception in 1988, Intakt has been an open organisation. Throughout the years of our existence, we managed to develop an entire vertical of education for children and adolescents from 4 to 16 years of age. This came in addition to the contemporary dance classes for young dancers and enthusiasts at different levels of their dance experience, as well as ballet classes for adults and contemporary dance class for older generations of dancers who have only begun to dance.

As I’m also interested in personal growth, we expanded our programme with Kundalini Yoga and Shakti Dance® - the Yoga of Dance classes about a decade ago.

I think it is safe to say that we are open to pretty much everyone who wants to join, since we cover the entire range of ages and backgrounds with our classes.

I guess you don’t teach all these courses by yourself, so who are the teachers?

As far as teaching is concerned, I originally started with contemporary dance classes for adults. Then I explored methods of teaching contemporary dance to children of various age and added those classes to our programme as well. I’m currently teaching mostly Kundalini yoga and Shakti Dance®- the Yoga of Dance classes, while our team of trusted colleagues are teaching other contemporary dance classes.

One of these is Igor Sviderski, who fell for contemporary dance at about the same time I did, in 1989. Like most of our generation of dancers, Igor studied dance abroad as well as at home, and has like most of our team members received several awards for his work as a dancer, choreographer and dance pedagogue. Igor currently teaches our Thursday Challenge class for adult beginners and Contemporary Dance I.

Another established member of our group is Sabina Schwenner, an award-winning dancer, choreographer and dance pedagogue from Novo mesto with a long repertoire of performances that begins in 1992. Sabina currently teaches the youth groups of Modrini (8-10 years) and Friksi (10-12 years).

There are, however, also younger members of our team, such as the talented Veronika Valdes, who started dancing at the age of four and soon after moved to perform at various local and international stages. In addition to the many awards Veronika earned in her time as a professional dancer, she has also proved indispensable as a teacher of our teen group Indigo (13-16 year olds) and Contemporary dance II.

There are many more teachers who have collaborated with Intakt and still do, among which I should not forget to mention Kristina Aleksova Zavašnik, our teacher for the youngest group Bube I (4-6 years), and also at the other end our older ballet learners (Ballet for Adults). After completion of her secondary education, Kristina joined the Opera and Ballet Ljubljana ensemble in 2002, where she also created several original performances. In 2017 she left the institutional milieu and began devoting herself to performance and contemporary dance.

What kind of a dance is contemporary dance?

Sometimes contemporary dance is misunderstood as the dance which is popular at a certain time, such as hip-hop now, for example. Contemporary dance, however, is an artistic practice with about a century old tradition, technique and aesthetics, which rather than into the fields of sport or entertainment belongs to the category of art. When we talk about contemporary dance we talk about dance as an art form.

If the main concern of sport and entertainment dances, even classical ballet, lays in the display of virtuosity within a certain prescribed sequence of body moves, contemporary dance in contrast focuses on the creation of the unexpected and novel. It presents an artistic tool that can create and communicate socially and emotionally engaged content. It can be critical and daring, as it allows us to go places nobody wants to go.

For these reasons contemporary dance is sometimes prone to taking itself too seriously, forgetting that being playful and cheerful are also worthwhile expressions of life. We dance barefoot, touch each other and play with gravitational forces.

My understanding of contemporary dance as an underlying concept behind the way I have been running the studio is that contemporary dance is a very democratic art form, which needs to remain open to everyone. And this especially important in today’s world of crisis and uncertainty.

We have therefore been placing a special emphasis on the dance education of children, since it is not only important for a child to receive early education in cooperation and mindfulness, as well as become more aware of their body through cheerful play, but it is also of a great importance to enabling future generations to enjoy this art and culture.

You joined Intakt Dance Studio about 27 years ago. How did your involvement progress to where you are now?

My first experience with Intakt was in 1989, when I took a course. Then I left to study at the Flemish Dance Academy in Bruges, and when I returned in 1992 Intakt had already lost some of its initial strength. I was with a group of young, enthusiastic dancers, and together we assumed a much more proactive role. We set up the entire adult education programme and started with our own productions and tours. Between the years 1992 and 1996 the public interest in contemporary dance courses was remarkable, and Intakt experienced a real boom.

We were a group of young dancers and choreographers who also developed as dance educators and created a vivid atmosphere in the courses with the fresh knowledge that we acquired at dance academies abroad. Later, in 1996–2003, Tanja Skok carried out a successful reorganisation and founded the PS Intakt study repertoire group, in which talented and dedicated dancers engaged in a creative process with renowned domestic and foreign choreographers. Many dancers from this period then continued their professional dance journey.

As already mentioned, in 2000 Intakt also acquired a quality creative dance programme for children and teens, which I designed with a group of experienced dance pedagogues.

Then in 2003 Intakt became an independent legal person, The Intakt Dance Studio Society – The Association of Contemporary Dance Artists. Until 2007 the society had been directed jointly by Tanja Skok and me, and since I’ve continued managing the studio on my own.

How can one join, and can adults and children with poor Slovenian skills take classes, too?

We have no language limitations. All the teachers speak English as well and I believe that so do most of our students.

Details on classes, the schedule and so on can be found in Slovenian on our website. Inquiries in English can also be made on our Facebook page. If someone wants to join a class, then they just need to fill in an application form or contact us at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

We are also approaching the open-door week starting September 7 - 11, when you can come and try out a class free of charge. Since the number of places is limited due to Covid19 measures, applications are required for these classes as well.

Nataša, thank you very much for talking to us.

You’re welcome.

Just as one needs to obtain a driving licence in order to drive a car, a boating licence is needed for someone who wishes to operate a boat. But what kind of boats need what kind of licences in Slovenia, and in which waters?

We met with Ambrož Jakop, a boat leading instructor at AJ Navtika to learn a bit more about how to get legal on the water and to broaden our perspective on the possibilities for adventure.

Who can apply for a boating licence, what are the limitations?

The boating licence exam can take any person who is 16 and older and has passed the first aid exam and medical examination. Since the latter two are the same one needs for a driving license, holders of any driving license (A, B, C, D etc.) are considered to be medically fit and have passed the first aid test. Until the age of 18, however, a holder of a boat licence may not operate boats longer than 12 metres or speedboats.

Are there different licenses one can get for various categories of boats?

Yes, you can either take the basic test that allows you to handle boats under 7 metres in length and with an engine below 10 horse power (7.35 kW), or the boat guiding test which includes five topics and will allow you to operate boats up to 24 metres and without engine power limitations. Both tests take place in front of the state commission at the Slovenian Maritime Administration, and the acquired licenses are also internationally valid. I teach courses that prepare the candidates for these exams.

Let’s say I pass the boat guiding test. Where can I take my boat then, in the sea or only in rivers and lakes?

Sea and fresh water sailing regimes are regulated by different legislations, which is why separate exams have to take place for taking a boat on the seas or in rivers and lakes. However, not many rivers or lakes in Slovenia have sailing regimes or ones that would allow the presence of boats with a mechanical drive unit.

So one doesn’t need a boating license in order to paddle a kayak or a SUP?

No, a license is not needed for sports equipment and vessels without a mechanical drive unit that are under 3 meters long. There are exceptions, however, such as an eight rowing boat, which is longer than that but doesn’t need to be signed in the boat registry, and therefore can be used without a license.

Where can people take a course to get a licence?

Due to the corona situation, we currently do the first theoretical 12 hours in an online course. The remaining 4 hours of practical charting of sailing direction, we do onsite, wherever a specific course is being held.

How did you become a boating license tutor?

At first I was just a sailing enthusiast. Then I established a sailing club and sailing school for children, sailing school for adults and then various courses. This was about 15 years ago when one still needed a Yachtmaster 100 BT license if you wanted to instruct courses, so I did that too. Soon my hobby turned into my job.

Do you have a boat?

I share a sailboat with my friends, a Y40 (40 feet), designed by the Slovenian architect Andrej Justin.

Where do you usually take it?

Mostly across the Adriatic. We’ve just sailed it from its berth in Koper to Lošinj and back home. Later this summer we are planning to sail alongside Dalmatia. And for this corona year, that will probably be all.

If you'd like to learn more about learning how to sail in Slovenia, then visit AJ Navtica here

Photos: Ambrož Jakop

I use my “professional” Twitter account for three things: occasional reposts of TSN stories, a moshpit for engaging with Brexiteers, and a way to learn Slovenian 280 characters at a time. With regard to the latter I follow local names and dig down into the tweets and replies, hitting Google Translate when needed and saving the texts for printing and study at leisure. It’s a lot of fun, and I like to think I’m progressing, but one person who certainly is Julia Borden, the woman behind the excellent Živjo Luka! account, which documents – a word or phrase at a time – her quest to master the language. Her joy of discovery is beautiful and inspiring, and intrigued by her tweets I sent along some questions to learn more, and she kindly replied…

When I first heard Slovene, I thought people were so friendly because everyone got adorable nicknames. Like Ana became Ani, Marko became Marku. Only once I started to learn the language did I realize that this was simply standard noun conjugation. #Slovenia

— ZivjoLuka (@ZivjoLuka) May 6, 2020

Who are you?

My name is Julia Borden. I’m from California and currently live here. I’m a PhD student and avid Slovene learner.

Why the interest in learning Slovenian?

My partner is Slovenian, and even though he speaks English fluently, I’m trying to learn to better communicate with him and his family. The language is really difficult to master, and I’m often frustrated with the grammar. But it’s also interesting linguistically, and I find it to be quite poetic!

I love that the word for plant, "rastlina", comes from the root "rast", which means growth. So a plant is "one that grows". So poetic and reflective of Slovenes being gifted gardeners and plant lovers! #Slovenia #LanguageLearning

— ZivjoLuka (@ZivjoLuka) June 19, 2020

I started the account because I wanted to capture everything I was learning and discovering. My partner and I both love basketball and Luka Dončić, and this was around the time that Luka was really becoming a sensation on the Mavs, so I thought it would be fun to base the account on my desire to talk to him one day in his native language. It’s maybe not the full reason I started the account, but it would still be amazing to say “Živjo!” to Luka!

What other languages do you speak, and how difficult do you think Slovenian is?

I’m a native English speaker, and a proficient Spanish speaker. Slovene is my first Slavic language, and man is it tough! The trickiest part is trying to learn the six declination cases, since we don’t have this in English.

Every time I try and say a sentence that requires noun and adjective inflection (which is all of them) I feel like I'm throwing darts at a board. Maybe it's -e? or -a? or -om? I'm right about 5% of the time, and those moments are pure joy. #Slovenia #LanguageLearning

— ZivjoLuka (@ZivjoLuka) June 16, 2020

When did you start learning Slovenian?

I started taking an online class through the Slovenian Union of America once a week about a year ago, though it ended in May.

What methods do you use, and why do they appeal to you?

Unfortunately, since not many people speak Slovene outside of Slovenia, there aren’t many easily accessible ways to learn such as through Duolingo, Rosetta Stone, or even university classes. I have 1,2,3 Gremo, and the class worked with the textbook Slovenska Beseda v Živo. Having a class and learning with other people helps a lot, since I’m not living in Slovenia, which would be the best way to learn! I also learn quite a bit through brainstorming ideas for Živjo Luka.

A basketball phrase for y'all: if you sink a basketball into the net it’s called “brez kosti” which means “boneless”. @luka7doncic we Americans out here tryin to learn some SLOVENE! Retweet so Luka knows we exist :) #Slovenia #LanguageLearning

— ZivjoLuka (@ZivjoLuka) June 12, 2020

Do you plan on visiting Slovenia?

I’ve been to Slovenia a couple of times, and I was planning to go again this June, but the coronavirus prevented that from happening.

What are some of the words, phrases that you find most interesting?

I absolutely love the unique idioms and phrases that Slovene has! Like “pojdite v gosjem redu”, “to imam v malem prstu”, and especially “tristo kosmatih medvedov”.

Next time you encounter a toddler with too much energy who is zooming around, you can do as the Slovenes do and tell them "imaš sršene v riti!" ("you have hornets up your butt!"). #Slovenia #LanguageLearning

— ZivjoLuka (@ZivjoLuka) May 25, 2020

How are you enjoying Twitter?

I’ve received some really great comments from people on Twitter, pointing out nuances of the language I hadn’t noticed or thought about. It’s been a great way to learn that takes me beyond the pages of a textbook.

Slovene has formal & informal "you". So if I say to a Slovene grandma "Kako si?" (how are you (informal)) she could say "Vikaj me!" (say formal "you" to me!) which is an informal way to tell me to be more formal. Meta manners. #Slovenia #LanguageLearning

— ZivjoLuka (@ZivjoLuka) May 17, 2020

With the introduction over, and a few examples shown in this story, it’s time for you to head over to Twitter and follow Živjo Luka!. But also click here to check out all our stories on learning Slovenian.

Where are you from, and how did you come to be in Slovenia?

I am from Uganda and I moved to Slovenia at the end of 2014 to join my boyfriend, who’s now become my husband.

How do you keep yourself busy here?

I travel a bit and I hold meetings and am passionate about talking about Uganda and some of the countries I have been to, to students or a group of people ready to travel to Uganda.

How is your Slovenian, and how well integrated do you feel with Slovenians?

It has taken time but I am improving each day with the language. I have a couple of Slovenian friends and so far I have got all my educational documents evaluated in Slovenia. I was worried that my education wouldn’t be recognised, but it was and my MBA still stands.

What has been your experience of culture shock?

Ah, this has been asked of me many times, and I have to think about it now since I’ve have spent some time here and travel a lot, things which shocked me are not issues anymore.

But I have to say that it was shocking at first when people seemed to either fear sitting near me or kept a distance. I kept on thinking what had I done or how I looked to be intimidating?. I came right from Africa to Slovenia and I didn’t know anyone or anybody except my husband, who is not very outgoing. I feared people more than they feared me. Someone even shouted at me at Zvezda Park ... if I was looking for ships. Now I laugh at all this because I don’t have time for such kind of people.

And of course I can’t forget the winter and summer. So hot and so cold for someone who is from Uganda, with an average temperature of 28 degrees. I come from central Uganda. The equator line is literally five minutes’ walk away from my home.

Also, although I’m not very social I came from an environment where I knew my neighbours and they knew me even when we lived in different houses. Now I live in a block but it took me time to know the people next door. Still, I feel accepted here.

Among other projects, Catherine also runs an Etsy store selling handmade African inspired products

Is there an organized African community in Slovenia?

Now this is a very interesting question. There quite a number of people who have opened up organisations relating to African communities and so on. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs also organises an African Days event every year to try to introduce the African countries to Slovenia in business perspective.

There’s nothing else that puts Africans together as a group for now, but I created a Facebook group for African Women in Slovenia where we help each other with information and we are few so we kind of know ourselves in a way. But as Ugandans living in Slovenia, we have a WhatsApp group and we meet every year for lunch to welcome anyone new and also to catch up.

Other things to mention are the Inštitut za afriške študije, the Afro Studio Black Diamond hair salon in Ljubljana, along with the Afriška Trgovina Petit Afrique store, and of course the restaurant Skhuna, on Trubarjeva cesta and the Nigerian Chamber of Commerce.

Why did you start your YouTube channel?

I realised that people know so little about Africa as a continent but they seem to talk about it in general. I want to show that there is more to Africa than the wars, hunger and diseases.

Some people know me as a person who talks about the effect of voluntourism. I am vocal about it because a big number of people don’t have any idea that charity and volunteering is more beneficial to the person doing it than the person they think they are helping.

If anyone is interested in learning more about Africa, then I recommend they subscribe and follow it, here.

If you'd like to share your Slovenian story with our readers, please get in touch at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it., or find me on Facebook

John Bills is the author of four books on Europe's better half, electronic versions of which are currently available at special lockdown prices, including a great deal on all four - just under £10 (or just over €11) for the lot with the promo code ENDOFDAYS at poshlostbooks.

Slovene history is littered with no shortage of talented writers. Quite the opposite, in fact, and I’d wager that this small chicken-shaped land has produced more wordsmiths per square kilometre than any other country in Europe. Fertile ground for the eloquent, that’s for sure. Every period of the nation’s history features men and women who have excelled in storytelling, taking the events and circumstances of the time to fashion tales that are as vital today as they were then.

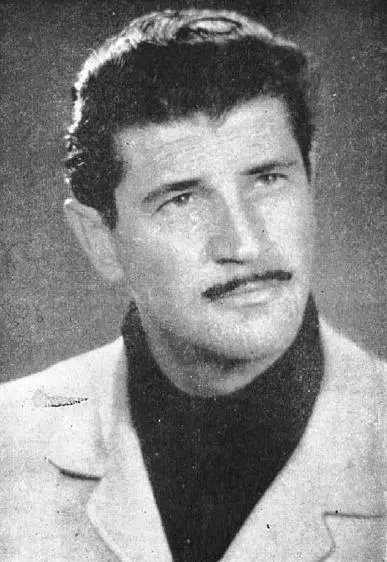

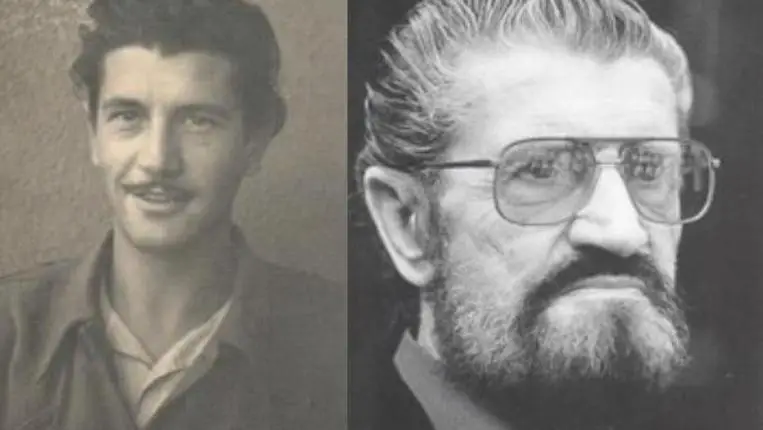

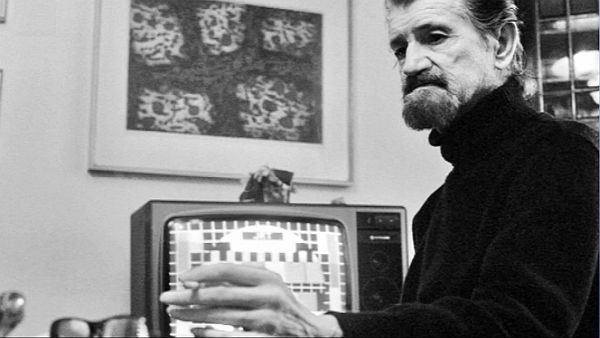

The writer has many jobs, many roles that must be played in the theatre of everyday life. Entertainers for sure, there must always be an engagement, but books go beyond mere titillation. Ljubljana-born Vitomil Zupan said it best in Leviatan (Leviathan [obviously]), an epic piece of work that details the day to day existence inside a Yugoslav prison; “…the wordsmith must be a chronicler of his times, and a chronicler must not be disgusted by anything”. In Zupan’s era, there was a lot to be disgusted by, but the modernist man turned his nose up at not a thing. In doing so, he became one of Slovenia’s most celebrated 20th-century writers, a man famed for his unwavering obsession with the edges of existence, his rapacious sexual appetite and a steely charm that positively bellowed “Hi, I’m your mum’s new boyfriend”. His life was eventful in all possible ways, but it was also a fascinating picture of Slovene creativity in those early Yugoslav days. Stigma, expression, productivity and oppression, repeated.

Vitomil Zupan was born just a couple of months before World War I began, and it didn’t take long for his life to encounter turbulence. His father was an officer in the Austro-Hungarian Army, and the Habsburg force had a pretty wretched record over the first years of the Great War. Casualties were high, and Mr. Zupan was one of the dead. Young Vitomil lived through the war and was a creative schoolchild, but his restlessness and ability to seek out trouble often, well, got him into trouble. The apex of this was a game of Russian Roulette gone wrong, a game that took place when Vitomil was just 17. His hand was on the trigger, his friend’s body was at the end of the barrel, the chamber was loaded. Russian Roulette is one of the few games that go wrong by going right. Zupan was expelled from school (a fairly light punishment, in hindsight), and he chose to hit the road.

Vitomil travelled long and far, crisscrossing the Mediterranean in search of new experiences and fresh excitement. His was a true vagabond existence, jumping from city to city and job to job, meeting people and moving on as often as was necessary. He worked as a sailor, a house painter, a ski instructor and more, even having a stint as a boxer. A strong jaw will take you far, never forget that. Zupan moved from Europe to the Middle East and North Africa, learning languages, cavorting with foreigners, learning how to thrive in new environments and in unfamiliar surroundings. Remember kids, if you can travel, travel.

Zupan returned to Ljubljana and continued his education, but he spent more time studying medical textbooks than concentrating on his own studies, feeding a constant need to understand his own emotions and tumultuous moods. The latter was dramatically exacerbated by the onset of World War II, which makes a lot of sense. Zupan immediately joined the Liberation Front and fought against the Italians, experiencing a number of battles before being captured and arrested. He was first sent to Čiginj concentration camp (near Tolmin), before being moved to the newly-opened Gonars camp in the north of Italy.

Established in February 1942, Gonars was a fascist camp specifically for Slovenes and Croats, people the Italians deemed ‘inferior’ and ‘barbaric’, those living in borderlands that Mussolini had his seedy eyes and grubby hands on. 5,343 men, women and children (1,643 children, to be precise) arrived just two days after it was opened, and the transports continued from there. Some of history’s most notable Slovenes were among them, men such as Jakob Savinšek, Bojan Štih, France Balantič and many more. Vitomil Zupan was another.

Vitomil Zupan managed to escape Gonars, and he immediately joined the growing Partisan movement Slovene, initially fighting on the frontlines before moving into the cultural department. He wrote plays that championed the socialist cause, encouraging Yugoslav patriotism in his fellow fighters and providing much-needed escape along the way. Following the war, he was rewarded with honours and a position at Radio Ljubljana, before the holy grail of a Prešeren Award for his novel ‘Birth in a Storm’ in 1947. Then Yugoslavia and the USSR had the big falling out, and it all went to the dogs.

Zupan himself put it best when he said that ‘there comes a time when one man can ruin ten people, but ten people can’t help one man’. The split filled Yugoslavia with pride, it was making its own way after all, but it also filled the halls of power with neurosis and paranoia. The national liberation, the class revolution that followed and the eventual split from the Soviet Union, these were holy subjects that were nigh on untouchable. Zupan was one of the few people honest enough to mention the shades of grey, to point out that everyone can be involved in a revolution but not everyone becomes a revolutionary, which explains the prisons. Those prisons would soon host Vitomil Zupan.

Truth be told, he was an easy target. He was a controversial cultural figure, one who was openly and passionately in touch with the more erotic desires of the mind, a man who had travelled extensively, spoke multiple languages, was comfortable in the presence of foreigners and was ruggedly handsome to boot. Oh, and that whole ‘shooting his friend’ thing. Zupan was sentenced to 15 years in prison, a term that was almost immediately increased to 18 because of his conduct in court. To prison he went, less for his ideas and more for who he was, what he knew and who he knew it about. There was no evidence, and barely any more of a defence.

Zupan only served seven of his 18 years, but don’t make the mistake of thinking that the experience was full of cheer. His already-compromised health took a turn for the worse, and for years he wasn’t allowed to read or write. He worked around these restrictions through character, ingenuity and how poorly-policed the jails were, compiling enough ideas and notes for one of his most famous pieces of work. Published in 1982, Leviatan (Leviathan) is a narrative of this time in prison, a torturous study of humanity that covers day to day atrocities, sexual frustration and release, violence, boredom and no small amount of black humour. The novel doesn’t really have a story outside of ‘this is what life is actually like in prison’. It is a vital piece of work.

Zupan’s major break came seven years prior, with the much-loved Menuet za kitaro (A Minuet for Guitar). This novel focused on his time in the war, a book based half during that conflict and half in the more relaxed atmosphere of a 1970s Spanish holiday resort, where soldiers from opposing sides (a Slovene Partisan and a Nazi) try to make sense of the whole thing. It covers all sides and all interpretations of the war and is every bit as ambitious as that suggests, and features one of the most pathetic, banal, poignant and perfect character deaths in the history of conflict fiction. It was adapted for film in 1980, given the new moniker Nasvidenje v naslednji vojni (See You in the Next War) in the process. A second Prešeren Award came in 1984, this time for his entire body of work.

There is a disjointed feel to Vitomil Zupan’s life story, a collection of contradictions that only seem to happen to those tasked with chronicling history in fictional form and blessed with the ability to do so. He was arguably more successful than any other persecuted writer from what was Yugoslavia. He won awards, experienced commercial and critical success, yet no publisher would go near his work in its original form. He wrote the most expressive Slovene books of his generation, but almost all of these works were heavily censored by the humdrum and the grey. He lived a life of tumult, adventure and penury, but everything seemed to happen to him so that he could write about it.

Vitomil Zupan died in Ljubljana on May 14, 1987 (the same day as Rita Hayworth, believe it or not). One of Slovenia’s most important and influential modernist writers, he is to the Slovene literary canon what Hemingway and Solzhenitsyn are to the west, combined. Such lazy comparisons are often difficult to avoid, especially when the stern eyes and imperturbable moustache of Vitomil Zupan, your mum’s new boyfriend, gaze in your direction.

John Bills is the author of four books on Europe's better half, electronic versions of which are currently available at special lockdown prices, including a great deal on all four - just under £10 (or just over €11) for the lot with the promo code ENDOFDAYS at poshlostbooks. You can enjoy more of his work on Total Slovenia News here.

John Bills is the author of four books on Europe's better half, electronic versions of which are currently available at special lockdown prices, including a great deal on all four - just under £10 (or just over €11) for the lot with the promo code ENDOFDAYS at poshlostbooks. The text below comes from An Illustrated History of Slavic Misery - as entertaining as it is educational, and as good as it is long, and at well over 500 pages it's very long indeed.

Who is the greatest swimmer of all time? Ask any chap on the street and they'll probably run away due to the strange question, but if they do manage to answer they will come out with the usual suspects. Mark Spitz, Ian Thorpe, Michael Phelps, maybe some other Olympians. The archetypical swimmer, the athletic body, the elegant technique, the great smile and in Spitz's example, the textbook moustache. What if I told you that none of the above can rightly claim to be the greatest swimmer of the human race? What if I told you that at the pinnacle of swimming you will find an overweight man, who may or may not be a raging alcoholic, born in the village of Mokronog in southeastern Slovenia? Ladies and gentlemen, let me introduce you to Martin Strel.

Who? Well, pretty much all you need to know is written above. Martin Strel was born in Mokronog on October 1, 1954. He’s overweight. He drinks a lot of alcohol. Oh, and he swims big rivers, from start to finish. And by big rivers, I mean BIG rivers. We're talking Danube big. Mississippi big. Yangtze big. AMAZON big. Martin Strel has created a legend of himself by swimming from the start of a river to the end of a river, usually in an astonishingly quick time, all in the name of greater awareness for the plight of the world’s rivers.

Mokronog itself has had little or no impact on the history of the world. It was once the centre of the leather industry, but the big factory was destroyed by the Nazis in 1943. 11 years later, Martin Strel entered the world. His early years were fraught with difficulty, as his father frequently veered into the abusive territory. As the legend goes, and with Strel the legend is as valid as the truth, his first swim was an attempt to escape the violence of his father. The tales continue, as he supposedly learned to swim by damming the Mirna river to create a pool. One day, when Strel was 10, a troop of soldiers raced in his pool, with a crate of beer for the winner. Despite being half their size and less than half their age, Strel won the race, and subsequently the beer. He has been swimming and drinking ever since.

He went to Ljubljana as a teenager, where he worked an assortment of odd jobs such as paperboy, mechanic and bricklayer. He was discovered, Hollywood style, at the age of 24, by the Yugoslav long-distance swimming coach. Within three months he had completed his first 20-mile race. It was his swimming ability that allowed him to get away with what must surely be a record 42 desertions of the Yugoslav army in his one-year service. That or his ability to complete a Rubik's cube in under a minute. He needed a job post-army though, so he became an infrequent guitar teacher (he's the finest flamenco guitarist in Slovenia) but mostly a professional gambler. Gambling, it could be argued, is the only thing he loves as much as swimming. And alcohol.

His first big swim came in 1992 when he swam the 63 mile Krka river in 28 hours. Non-stop. It was a cold and miserable experience, understandably, but it gave Strel something approaching a new goal, a new mission in life. He was going to do all he could to promote awareness of the state of the rivers of the world, of their pollution, of their decline. As he said himself, without water we are truly nothing. He was going to do this by swimming the longest, most imposing rivers in the world, and he practiced by becoming the first man to swim from Africa to Europe, in 1997. Seven had perished attempting this feat before him. He swam the Danube, the second-longest river in central Europe at 1,867m, in just 58 days. During this swim, he also managed to set a world record for the longest continual swim, when he swam 313 miles in 84 hours, non-stop.

Just let that sink in for a second. 313 miles. Three Hundred, and Thirteen miles. For 84, Eighty-Four hours non-stop. Doing anything for 84 hours is difficult. Heck, doing any single act for four hours is hard enough. Being awake for 24 hours is often impossible. But swimming, for 84 hours? Awe my friends, awe and respect.

He followed this feat by swimming the length of the Mississippi, two thousand three hundred and fifty miles, in 68 days. Then, he swam the Yangtze, China's behemoth (2,487m), in an astonishing 51 days, all the while dodging waste and corpses in one of the most polluted rivers in the world. This was all in preparation for his ultimate challenge, possibly the ultimate challenge in the world of big river swimming. It might not be the longest river in the world, but it is the most difficult regarding swimming. I'm talking about the Amazon.

To describe the Amazon swim as a challenge is a grand understatement. It is doing a disservice to what Strel achieved with this swim. It was such a huge, ambitious project, that a documentary was to be made about it, entitled 'Big River Man'. Strel swam 3,274 miles in 66 days, sleeping around four to five hours a night at most. He could rarely see below the surface of the dirty water and constantly had to deal with the threats of pirates and with tribes that were hostile to his presence and considered Strel to be a demon. This without mentioning the animals that live in the Amazon, the dangerous bastards that Strel would contend with on a day-to-day basis.

The list is pretty much the most terrifying list of all. The Amazon is home to the Bull Shark, the shark that is believed to have killed more humans than any other of its kind. Then there are the piranhas, often considered the most vicious of all fish, stingrays, electric eels, crocodiles, catfish that swallow dogs whole and snakes, oh the snakes. There are so many different types of snake in the Amazon. Oh yeah, and the Candiru, which gets into you through any orifice, locks itself in with a spike and then feeds on your blood. It's most famous route is through your urine, by the way, that is to say through your urethra and up your schlong. This isn’t exactly true, but that doesn’t mean I’m going to be heading to the Amazon riverside for a tinkle any time soon. The natives don't swim here, so how would an obese alcohol-fuelled Slovene cope?

Well, he went mad, quite obviously, but he managed to complete the course without any interaction with the animals other than a brief spat with some piranhas. He claims that this is all because of the respect he showed the nature, that and the fact he was escorted a large portion of the way by a group of pink dolphins. That sounds like something out of a crazy dream obviously, and it might be, but the fact is that Martin Strel swam the length of the Amazon, a distance that is longer than the width of the Atlantic Ocean. Let that sink in as well, because holy moly that is a loooooooong river. He did this whilst under immense pressure due to the increased profile and huge production that came along with it. Many livelihoods depending on his being able to continue swimming. His skin blistered to the point where he had to swim in a home-made cloth mask which looks like that worn by an insane asylum dweller in the nineteenth century. His doctor even made him sign a waiver stating that he was swimming against her advice. But still, he did it. Somehow, he did it.

Whatever your opinion of him, it is difficult to not view the achievements of Martin Strel with awe and respect. He drinks two bottles of wine a day and is a fervent believer in the benefits of being overweight. If I was swimming 52 miles a day, I would require some sort of fatty reserves, and Strel has them in abundance. He is a very bullish, confident man, prone to embellishment. Why wouldn't he be? Every time I attempt to criticise the man, I keep coming back to thoughts of his swims. The length of the freakin’ Amazon. Let the guy be rude, he swam for 84 hours non-stop. He's earned the right to be insane.

I wouldn't just say Martin Strel is the greatest swimmer in history. I'd go so far as to say he is the greatest athlete in the history of the world. A modern-day Atlas.

John Bills is the author of four books on Europe's better half, electronic versions of which are currently available at special lockdown prices, including a great deal on all four - just under £10 (or just over €11) for the lot with the promo code ENDOFDAYS at poshlostbooks. The text above comes from An Illustrated History of Slavic Misery - as entertaining as it is educational, and as good as it is long, and at well over 500 pages it's very long indeed. You can learn more about Martin Strel at the man's website, and even go open water swimming with the tour company he and his family run, when this whole covid-19 thing is over.

Where are you from, what brought you to Slovenia, when, and where do you live now?

We're originally from Liverpool, UK. After getting married, we quit our jobs and sold everything to travel the world with the intention of finding a new country to live in. As part of the trip we spent three weeks in the Balkans, where we fell in love with Slovenia. A massive love was the natural wine! After the trip, we went back to the UK, had our daughter and five months later, March 2019, moved to Šiška, Ljubljana.

What were your first impressions of the country?

We love how compact Slovenia is, the sea, lakes, mountains, forest, access to other nearby countries; the fresh food, farmers markets and natural wine. Slovenia is the way people should live.

We walked to the park on Saturday and there was the lake, as usual, but that day it was frozen, with teenagers playing ice hockey and young children skating around.... I love the joy small things can bring to people here.

What’s your experience of culture shock been like?

The biggest culture shock has been the unexpected Slovenian holidays (e.g. St Martins Day) that our kitchen cupboards weren’t prepared for!

Language is our main hurdle but we have been using language apps and books and will probably start lessons soon.

What do you do for a living here?

Both worked in finance in the UK, and now my husband works from home here and I have just finished my first prenatal yoga and positive birthing class, in English. The most difficult part will be working out how/where best to advertise.

What’s your background with yoga?

What are the benefits of yoga for pregnant women?

Yoga has so many benefits at all stages of life. It's especially good for pregnant ladies because the poses are gentle and can be adapted to everyone, irrelevant of flexibility or fitness. Particular benefits include, strengthening the important muscles and increasing flexibility, making mum more comfortable in her ever-changing body, reducing stress and improving sleep, and enhancing the connection between mum and baby.

And my yoga classes have the added benefit of giving mum confidence as she learns how to birth with pleasure and trust herself.

Where and when will the classes be held?

1-2-1 classes can be arranged anywhere. I have three classes per week scheduled in Rudnik, Bikram Yoga Ljubljana (it's a beautiful hot yoga studio – but it will not be hot for my classes). And I'm looking for venues both in the centre and in Šiška too.

No yoga experience is necessary and it’s suitable for all stages of pregnancy. Please contact me with any questions. People can learn more on my Facebook page, Pregnancy Yoga with Sarah, or email me at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

If you’d like to share your story with our readers, please get in touch with me at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.