April 3, 2018

Hiša Eksperimentov, or the House of Experiments, has been a fixture on Trubarjeva cesta, Ljubljana, for around two decades now, bringing science, experiments, learning and fun to visitors of all ages throughout the years. In addition to its work in the building, which you’ll find not far from Three Bridges, and is well worth the visit, it also runs an annual science festival that takes to the streets each June, as well as making visits to schools throughout Slovenia, with such efforts dedicated to realising the vision of founder and director Miha Kos: working for a better society of more curious and self-directed individuals.

I met up with Miha in his office in the centre, surrounded by boxes of experiments and equipment, plans stuck to the walls along with cartoons by his father, a hammock hanging from the ceiling and his dog, Tač, resting on the floor. “He’s a great Zen master,” Miha says, “I learn a lot of from him.”

Tač, the Zen master at Miha's feet

How did it start?

I’m a physicist. I did my PhD here, and then for my post-doc I went to the US, to Albuquerque, New Mexico. I was doing scientific research, collecting points, and so on. I was also an assistant professor at the university physics department.

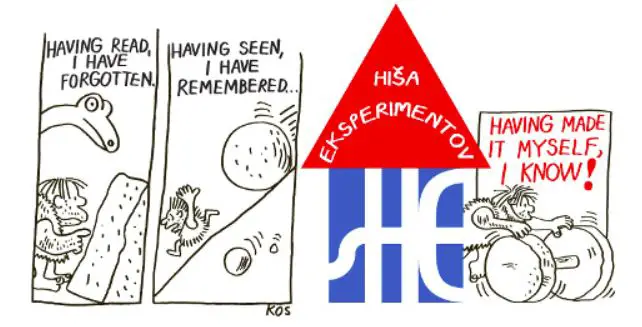

But I always liked to read popular science books. And my father, who was a very famous cartoonist in Slovenia – Božo Kos – he also studied physics and was my role model. All the pictures you see in Hiša are his. When I was a child, instead of telling me fairy-tales we did experiments.

When I was working the lab some people told me I should go to see the Exploratorium in San Francisco, which is really the mother of all science centres, established by Frank Oppenheimer, the brother of Robert. It was his idea to promote learning though experimenting yourself. When I entered this place in 1995, it was a big change. I saw something that I always wanted to do, but I didn’t know it existed.

Then when I came back here I made it my goal to set up a science centre in Slovenia, which was no easy task, because no one knew what that was. I had to do a lot of lobby, I guess you’d say, and promotion, networking. I had to get a critical mass of scientists, politicians and financial supporters, like companies. Then in 1996 we established a non-profit foundation, so now we have been operating more than 20 years.

At first we made some exhibits and put them in two suitcases, and I’d travel around and show them to people, to help explain what we wanted to do with this projects. This worked better in some places than others, but it was enough to get attention, and so we started with temporary exhibits. Then in 2000 we got this place here. It’s owned by the Municipality of Ljubljana, so we don’t pay anything for the rent, just the electricity and so on.

There have been many ideas and discussions about enlarging the centre, but the governments keep changing. Even now there are plans, but it’s in muddy waters. When you have an idea and no money, everybody agrees you’re doing a good job. When there is money for it there are always parasites that start appear and start to grow from nowhere, and then instead of doing what you do, what you’d like to do you have to concentrate on other stuff.

The philosophy underlying the House of Experiements, with drawings by Božo Kos

How many of the exhibits do you make here?

We design and make them all by ourselves. They always evolve and we keep on improving them constantly. Some of the exhibits you can experience elsewhere although we always give them some Hiša touch, but most of them we created from scratch. We have a small but very strong planning and development department, and so there are new things every year. But the centre is not just this building. Because of the limitations of the space we have to go outside, and one of our outreach programs involves the organisation of the science festival.

Children discovering the world. Screenshot from YouTube

Like the summer festival in Ljubljana?

Yes, the one we do in Ljubljana is called Znanstival, and it takes place in several main town squares, on the bridges and pedestrian zone, always at the beginning June and from Friday to Sunday, and this year (2018), the tenth edition, it’s June 1–3.

Before that we’ll have an international, five-day workshop on how to create and run science shows. We’re very strong in these and have a special philosophy, which means we’re well known for this within Europe and elsewhere. This year we’ve invited people from the US, Israel, Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary and so on. There’ll be a five-day workshop that runs from Monday to Friday, ending the same day as the festival starts. The participants will learn how to make and perform a science show, with our help, theoretical and practical, and the last day is like the final exam, when they perform it in front of the public.

What can people expect at the festival?

A lot of things, but every year we also have some kind of spectacle. For example, once we put a wire over the river, and built a bicycle with the centre of gravity below the wire. Then anyone who wanted to could cycle over the river. Then a few years we’ve set it up so people could run on a non-Newtonian liquid, and last year we had a workshop making something like a pneumatic robotic hand, made of paper, syringes, and so on. The year before we had an astronaut landing on the Earth. The astronaut was an egg, and people had to make a landing craft. We cooperated with the fire brigade, and they brought a big truck and we dropped the craft from the top of a long ladder, to see if the egg would survive.

What about your other programmes?

We have something called Hiška Eksperimentov, which is like “small house of experiments”, where we have about 70 mobile, hands-on exhibits. We put them in our van and take them to a school somewhere in Slovenia and take over a couple of classrooms, say, or the gym, and turn that into a science centre and do shows for the children. Then in the afternoon the school opens to the public, and they can try it all themselves.

Hiška Eksperimentov makes a visit to Cernika. From the House of Experiment's webpage

How has your vision for this place changed?

We started with the promotion of science, then turned to the promotion of learning, and I’d say that now our goal is help create a healthy democracy. This means that the majority of people who can think critically and are proactive. And you’ll note there’s no science, as such, in this vision.

So this place is for everyone?

Yes, not just for children, but anyone who’s capable of admitting that he or she doesn’t know everything, that has the passion to learn something new. Because it’s a chain. You need curiosity in order to get creativity. You need creativity in order to be innovative. You need to be innovative to be entrepreneurial. And you need entrepreneurs to make the state healthy.

That’s why I think it’s so important for people to become critical thinkers, especially nowadays, when you have so many false truths everywhere, with believers in horoscopes, homeopathy, fortune tellers and so on. What we do here is not so much empower people directly, but help people to empower themselves, to think critically, to ask questions, and not be happy with answers they don’t understand.

And it’s not just the vision that has changed, it’s also the exhibits, because we’re really a research institution, and we have many innovative approaches. For example, we can turn all of the exhibits on or off using a computer. Not only that, we have sensors and they measure the power dissipation of an exhibit, if people are interacting with it, how much time they spend with it, and so on.

Another interview with Miha, this one in Slovene with English subtitles (just press CC if they don't play automatically)

What about the staff here?

Now we have nine full-time staff. I’m physicist, and we have another two who also studied pedagogy. We have meteorologist, who’s our IT person, and we have two geographers, someone who studied art history, and great technicians.

But those people who do demonstrations or work on the floor, who wear yellow T-shirts, they’re from all kinds of different faculties. These people have to be communicative, and also – the most important thing –they mustn’t talk about things they don’t know. This is key, because one of the foundations of our science centre is to say “I don’t know” for the things you don’t know. Not to bluff, not to say rubbish.

Similarly, if someone asks anyone working here a question then they don’t give the answer. Instead, they answer with a question. So if you ask someone in a yellow T-shirt “How does this function?”, the right answer would be “What do you think?” We do that for almost every question, except “Where’s the bathroom?”

A visit to Škofja Loka

And this is you try and teach people about science?

No, we don’t try and teach people, because I’m convinced that no one can teach anyone anything. All you can do is make someone interested, and then they learn by themselves.

This is the problem with most education systems: we have teachers. We shouldn’t have teachers in schools, we should have inspirers, people who make children interested in something, so they learn themselves, and this is what we aim for.

You can see this in our science shows. They have scenarios, and the people who present them have to know them, but the important thing is to start a free-from discussion. When one starts you have let it flow, to let people start talking and sharing their ideas.

No question is a stupid question, because it’s a trigger for dialogue, and I think this is something that we need in our education system, rather than just dragging children through the curriculum. If you have a pupil who asks a question, then this should be the most important thing for the teacher at that moment.

The teacher may respond “I don’t know”, or “Very good question, does anyone have any idea?” This is a trigger for curiosity, and it makes not just the person who asked the question curious, but it inspires others. It shows that even such a person as a teacher doesn’t know everything. This is something amazing for children, and it really opens things up.

In contrast, if the teacher says, “You should know that by now”, or “We’ll learn about it later”, or other such killers of curiosity, well that shuts things down for the whole class, because they see that curiosity is being punished.

Curiosity is rewarded. A screenshot from YouTube

Do you think things are getting better?

Yes, but of course I’m an optimist, otherwise I wouldn’t have changed my career. And the team I have here is great. It’s like I’m looking at my watch on Sunday and wondering when will the day end, so I can come back here and go to work again.

The House of Experiments is open for all visitors every Wednesday from 16.00 to 20.00 and every Saturday and Sunday from 11.00 to 19.00. On Saturdays and Sundays a science adventure, like a short lecture with experiments, is at 17.00, although note that this is held in Slovene only.

Tickets for one person are 6 EUR, for visits are 24 EUR, annual membership is 30 EUR, and – best value of all – an annual family ticket (4 visitors at a time) is just 60 EUR.

You can find the House at Trubarjeva 39, 1000 Ljubljana, while the website is here.